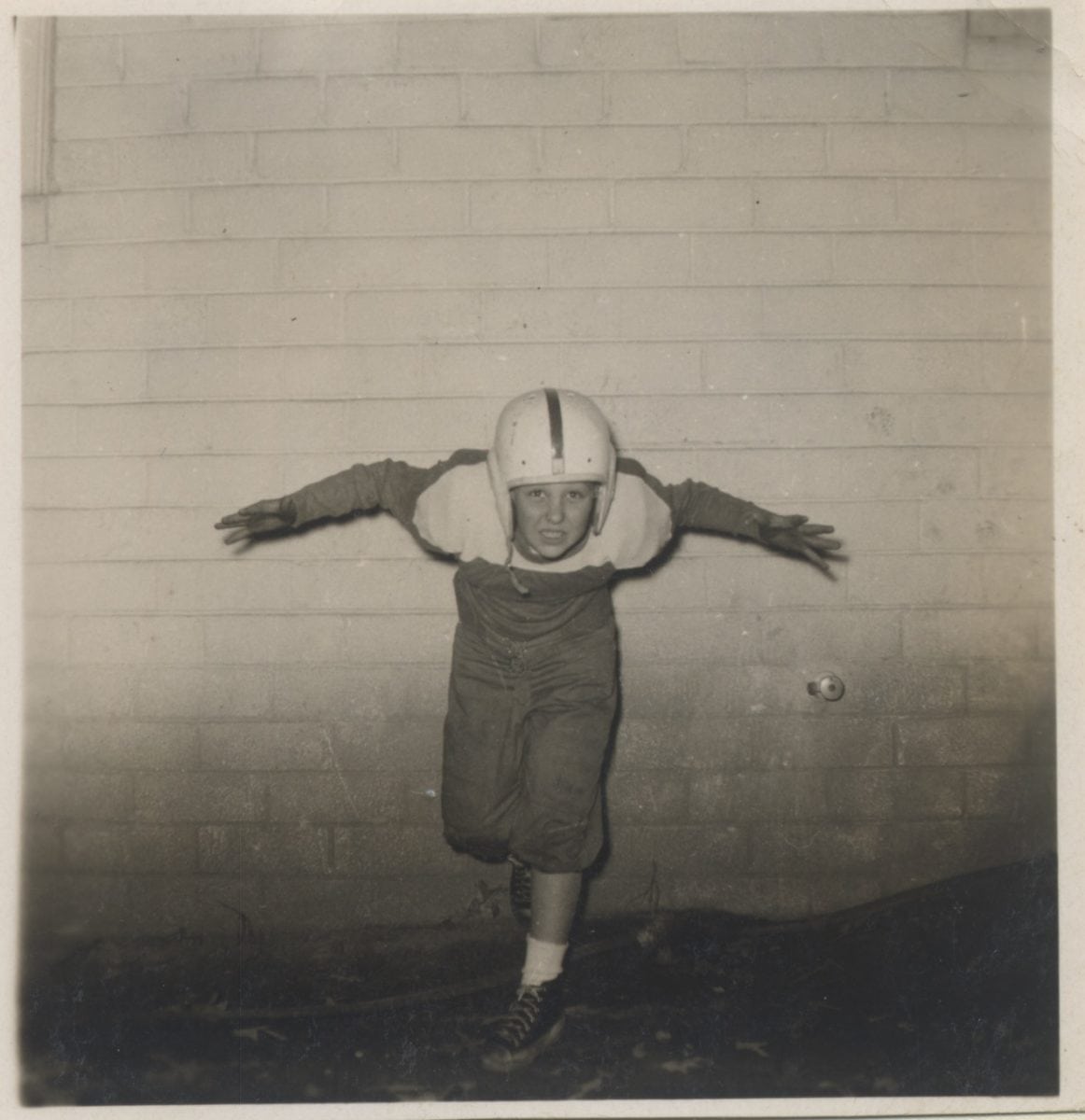

This time of year, my thoughts turn to that uniquely American and profoundly southern institution of football. As high school and college teams begin their seasons, I am reminded of my illustrious football career. Some of you may recall how my running and passing skills as a quarterback dominated the Knoxville/Knox County high school football league during the fall of 1958, 1959, and 1960. For those who have trouble remembering that phenomenon, perhaps the photo of me as Bearden’s quarterback will jog your memory. While I and my pad-pounding, Friday-night-warrior brethren often revisit the “glory days” and exaggerate our athletic prowess, most of us in our beloved East Tennessee love the sport and this time of year. My true athletic specialty was running onto the field and trying to look good while I paced the sidelines.

Preseason football camp for the Bearden High School teams in the late 1950’s was an exercise in torture the likes of which would not be allowed these days. Bear Bryant, the famous Texas A&M and later Hall-of-Fame coach for Alabama, decided that taking boys away to a harsh environment and exacting physical and mental torture would not only increase physical fortitude and allow focus on the team concept, but it would bond boys and even help them achieve manhood. I only point this out so that I can say that my name and Bear Bryant’s name once graced the same article. This “Junction Boys” method resulted in a trend in coaching that was accomplished by isolating the team far away from home and hammering its members in intense two-a-day practices. It was the preferred method in those days to shake off the weight and laziness that had set in during summer months. We Bearden boys were bused to Crossville where we, along with the members of the Oneida High School team, practiced and drilled until we could not walk. It felt like prison.

Each morning started with a two-mile run and exhausting calisthenics. I usually finished the run with the guards and tackles. Two scrimmage sessions a day in the hot sun on a field that was part grass and part rock were more than most high schoolers could take. Although some may have been turned from boys into men, I was just 16 and the methods created in me a strong preference to remain a boy just a little bit longer. Confined against our will at “Camp Crossville,” we were convinced we were in prison. It turns out we were.

Each morning started with a two-mile run and exhausting calisthenics. I usually finished the run with the guards and tackles. Two scrimmage sessions a day in the hot sun on a field that was part grass and part rock were more than most high schoolers could take. Although some may have been turned from boys into men, I was just 16 and the methods created in me a strong preference to remain a boy just a little bit longer. Confined against our will at “Camp Crossville,” we were convinced we were in prison. It turns out we were.

Between 1942 and 1945, approximately 400,000 Germans and Italians were detained in over 500 prisoner of war camps across the U. S. and mostly in the South. “Camp Crossville” had been the site of a 1930’s Civilian Conservation Corps work camp. After Pearl Harbor and the entry of the United States into World War II, 1,500 German and Italian prisoners were housed there after being captured. In those days, locals referred to the camp as the “Jap Camp,” even though no Japanese prisoners were detained there. Today, it’s known as the Clyde York 4-H Center.

On my first trip to “Camp Crossville” in 1958, I was the fourth-string quarterback for the mighty Bulldogs. I had transferred to Bearden in the 10th grade and decided to play football to make friends. I also figured girls liked football players and decided I had a talent for looking good in a garnet uniform. When I stepped onto the makeshift field in Crossville, it was the first time I exposed myself to premeditated violence. I had been a superstar in Corky Goldman’s back yard as a child, but I had never been really hit. I had played organized team basketball and thought maybe my skills would transfer to the football field. When our senior starter quit the team, I received a quick promotion to third-string quarterback. Shortly thereafter, it was decided that our best athlete, who had become first-string quarterback, should play running back. This made me the second-string play caller with little or no effort on my part. Just as I was getting over the anxiety of accepting my undeserved ascendency, and while we were imprisoned and struggling to stay alive, it was discovered that our first-string quarterback was color blind. This affliction became apparent when he kept throwing the ball to the other team. I was informed that I was the first-string quarterback and would be starting in our first game of the year, and the first game in my life, against the perpetual champion and powerhouse of East Tennessee football: Kingsport’s Dobyns-Bennett High School. I didn’t deserve this. I had only wanted to make friends and wear a uniform.

Although my arm was questionable and my speed was nonexistent, I had a talent that even the greats never master. My coaches told me that I was a deceptive ball handler, capable of allowing me to fool a committed linebacker or cornerback with fakes and concealment. My ability to act and deceive would eventually lead me to the doors of the College of Law and a 50-year career in the courtroom, but on the patch of field where German prisoners exercised, it simply allowed me to survive.

We lived in the same barracks that had housed prisoners only thirteen years earlier. We used the same latrine and mess hall. History reports, however, that the prisoners had it much better than we Bearden footballers had it. We were running through the woods at 6:00 a.m., while the prisoners did not rise until 8:00 a.m. After breakfast and roll call, the officers enjoyed leisure time for the bulk of the day, and the enlisted men went off to work on Cumberland County farms or in factories. In 1958 and 1959, the Bearden football team blocked and tackled in the hot sun and had virtually no leisure time. The Germans had no curfew inside the encampment and they governed themselves. The Bearden football team had a strict curfew and were enthralled to the coaching staff. Benevolent treatment was common in the American prisoner of war camps, and there was very lax security. Every morning at roll call, the Bearden football team would be missing one or two players who had deserted overnight.

Nationwide, there were few deserters from prisoner of war encampments in the U. S., but on one evening three German enlisted men did escape from “Camp Crossville.” They were heard late at night behind a mountain cabin pumping water from a widow woman’s well. She got her gun and shot into the darkness, and one of the prisoners was killed. When the sheriff came to check on the shooting, he informed the lady that the men in her backyard were German escapees from “Camp Crossville.” In her distress, she claimed that if she had known they were Germans she would never have fired the shot. “I thought they wuz Yankees,” she said.

In 1944, the Germans at “Camp Crossville” had an orchestra and published a newspaper run by the inmates. Beer and wine were allowed to be purchased with their earnings from work in the Crossville community. Classes in English, chemistry, and math were taught and even piano lessons were available. The poor Bearden football players had no beer or wine to enjoy and weren’t even allowed to drink water during practice (another stupid trend in coaching). While we didn’t have an orchestra, we did regularly march around single file in a conga line, singing “Folsom Prison Blues” in the barracks.

One thing the football players did have in common with the prisoners is that we both ate well. Full and complete breakfasts were served for both the prisoners and the football players. Eggs and bacon, grits, and potatoes for breakfast – vegetables and fried chicken for lunch. There was always a big supper with plenty of milk, breads, and desserts. In 2004, Gerhard G. Hennes, a former prisoner at “Camp Crossville,” published a memoir entitled The Barbed Wire: POW in the U.S.A. He reflected in his book about 1944, the same as I recall about 1958 and 1959, on the great food that was served in the “Camp Crossville” mess hall.

I am sure that the only reason I survived three years of high school football was because of my experience with the hard exercise program and intense training that I received at “Camp Crossville.” I never thought I’d live to respect that experience, but as a 16- and 17-year-old boy, it was good for me to have been forced to endure such brutality. I was stronger in body and mind for having had that experience. Looking back 57 years, we were a good football team and won most of our games, but I can’t remember any specific game and no scores. Turns out I was not playing football so much as I was really making friends as I first intended. In sport, as in life itself, it’s not about the games we play, but the relationships we make along the way.