They’ll watch the game and it’ll be as if they’d dipped themselves in magic waters. —Terrence Mann

Baseball, beginning in 1876, remains to many as

our national pastime. In the words of Babe Ruth,

“Baseball was, is, and always will be to me the best game in the world.” Commentator and author George Will, no fan of football, famously wrote: “Baseball, it is said, is only a game. True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona. Not all holes, or games, are created equal.”

In 1922, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for a unanimous United States Supreme Court, added the judicial stamp of approval, declaring that baseball was entitled to an exemption from federal antitrust laws—a monopoly status no other professional sport has enjoyed. Although the decision has been roundly criticized in recent times, 1953 and 1972 Supreme Court opinions have upheld the ruling. Congress has done nothing to alter the situation. Thus, baseball occupies a cherished status in the eyes of the law.

Over the years, Hollywood has promoted the image, romanticizing the sport with such films as The Pride of the Yankees, The Natural, Bull Durham, Moneyball, Eight Men Out, A League of Their Own, and so many others. From the sublime to the ridiculous, compare the film version fantasies of Damn Yankees and Angels in the Outfield with the fun-filled antics in The Bad News Bears and Major League. Stars like Robert Redford, Madonna, Brad Pitt, Clint Eastwood, Geena Davis, Gary Cooper, Charlie Sheen, Susan Sarandon, Kim Basinger, Robert Duvall, Glenn Close, Robert De Niro, and, of course, Tom Hanks, have all appeared in box office hits related to the sport.

Of special mention is the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, which featured Burt Lancaster in his final role as an actor and Kevin Costner in the starring role. The plot was built around a mystical voice heard only by an Iowa corn farmer threatened by bank foreclosure, saying, “Build it, and they will come.” The Terrence Mann character, played so compellingly by James Earl Jones, delivered a memorable tribute to the game:

“The one constant through all the years has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game – it’s a part of our past…. It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again.”

On August 12, 2021, Major League Baseball scheduled a televised regular season game in Dyersville, Iowa, at the filming location of this titular movie. The players for the Yankees and the White Sox emerged from the cornfields beyond the center field bullpen just as did the legendary Shoeless Joe Jackson and those other ghostly players in the film. For fans of Field of Dreams, experiencing the real game was truly magical. As a Hollywood touch, Kevin Costner threw out the first pitch. When the last pitch was thrown, the teams had combined for a total of six home runs. Each of the round trippers, including two by current home run king Aaron Judge, landed in the cornstalks. The last, launched in the bottom of the ninth inning, won the game for the White Sox, 9-8.

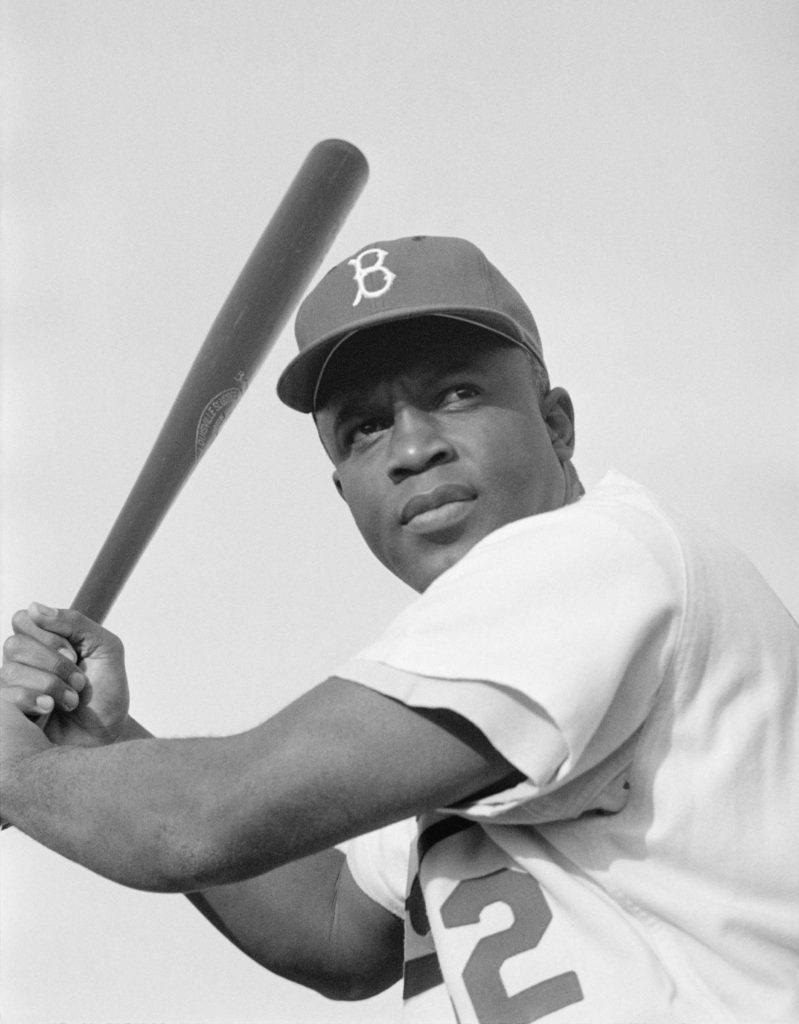

Yet for all the good in the hardball sport, its history is stained by a colossal blemish. If the original sin in this country was slavery, as many say, baseball “compounded the felony” for far too long by the exclusion of African American players. The case of Jack Roosevelt Robinson, who was born in 1919 and named for President Teddy Roosevelt, illustrates the point. After his family moved from Georgia to California, “Jackie” starred in football, baseball, basketball, and track in both high school and junior college, thereby earning a scholarship to the University of Southern California. As a junior, and while participating in two other varsity sports, he set a rushing record at the school in football which still stands today—an astounding 12.2 yards per carry. Drafted in World War II, Robinson was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army. When, however, a bus driver for an integrated bus line ordered Robinson to move to the back, he angrily refused.

The driver’s complaints to the military eventually resulted in a court martial. Although the charges were ultimately dismissed, the length of the proceedings deprived Jackie from overseas deployment. After he was honorably discharged, Robinson served a short stint as a small college athletic director, but soon signed on with the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Baseball League. He earned All-Star status in his first year as his team’s shortstop. A subsequent invitation for tryout with the Boston Red Sox of the American League turned out to be a publicity stunt, designed primarily to assuage the desegregationist sensibilities in Massachusetts (The Red Sox were the last team to field an African American player). Jackie’s interest in breaking baseball’s color barrier did not go unnoticed by Branch Rickey, the club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

From this point, the big screen, with some embellishment, takes over the Robinson story in the 2013 movie, 42. Harrison Ford undertook the role of crusty pioneer Rickey and the late Chadwick Boseman starred as Robinson. In the initial interview with the Dodgers, Jackie asks, “Do you want a player to have the guts to fight back [to the expected racism]?” “No,” says Rickey, “I want a player who has the guts not to fight back.” Jackie pauses before the response, “You give me a uniform and a number, and I won’t fight back.” After a year with the minor league team in Montreal, Jackie was awarded number 42 for the big-league Dodgers. By then, he was at the relatively advanced age of 28 when most first-year players were in their early 20s. Despite objections from the other team owners and racist taunts wherever he played, Rickey and Robinson were steadfast in their resolve. Jackie’s conduct and superior play facilitated the process. He won Rookie of the Year in 1947, and, in 1949, he was voted the Most Valuable Player in the League. After his retirement in 1956, he was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame located in Cooperstown, New York.

A memorable scene in the 42 movie takes place when Rickey asks a front office employee, “Do you think God likes baseball?”

“What the hell does that mean?” his colleague responds.

“It means someday you are going to meet your Maker, and when he inquires as to why you didn’t take the field against Robinson, you answer because he was a Negro, that may not be a sufficient reply.”

“Jackie’s a Methodist. I’m a Methodist. And God’s a Methodist. We can’t go wrong!”

Technically speaking, Robinson was not the first African American player in the big leagues. In 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker played, ironically, 42 games for the Toronto Blue Stockings before an injury ended his career. He was the last African American to participate in a major league game until Robinson debuted with the Dodgers on April 15, 1947. In 1997, Major League Baseball retired number 42 across all National and American League teams, making Robinson the first professional athlete in any sport to be so honored. There is a single exception. On Jackie Robinson Day every April 15, each player in both leagues wears that number in tribute to his memory. After Robinson’s death in 1972, he was awarded both the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of his leadership both on and off the field.

Comments are closed.