After 50 years in Knoxville, Richard Jolley reflects on a life shaped by fire, glass, and the radical choice to build an exemplary career without ever leaving home.

By Nathan Sparks I Photography by Molly Herb

Appeared in Cityview Magazine, Vol. 42, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2026)

O

n a gray morning in Knoxville, the front door of an unassuming studio swings open and the temperature jumps. Inside, the air shimmers with heat. Furnaces roar. Pipes turn slowly in practiced hands. At the center of it all, a tall man in a dark T-shirt leans into the glow of molten glass as if he’s listening to it. The first time I saw that image was over 10 years ago.

That was and is Richard Jolley’s world—a place where sand, fire, and breath become birds in flight, contemplative faces, and entire constellations of color. It’s a world he has been building here for fifty years.

In 1975, when most young artists were told they’d have to leave home and head for New York or the West Coast to succeed, Jolley did something quietly radical: he set up a glass studio in Knoxville and stayed. From that decision came one of the most accomplished careers in contemporary figurative glass. His work has been exhibited and collected around the world. But Jolley’s legacy remains deeply rooted in East Tennessee. And this year marks the 50th anniversary of the studio that made it all possible.

Oak Ridge Roots, a Different Path

Jolley grew up in Oak Ridge, the son of a research scientist. In a town built on physics and engineering, there’s an unspoken script for success.

“Being raised in Oak Ridge, I missed the memo that I was supposed to be a doctor or an engineer or a lawyer,” Jolley says, with his trademark dry humor. In 1970, he arrived at Tusculum College and enrolled in a newly formed glass class—an elective that would quietly redirect his life. Within a year, he decided to try turning that class into a livelihood.

The timing mattered. The early ’70s were steeped in counterculture and skepticism toward corporate life. “There was sort of an anti-corporate feel for people trying to be creative,” Jolley recalls. Becoming an artist felt less like a career choice and more like

a philosophical one.

He continued his studies at George Peabody College in Nashville and later at Penland School of Crafts, absorbing both technique and discipline. Glass wasn’t just a material; it became a way of thinking.

Choosing Knoxville

Knoxville was not the obvious choice for a young glass artist in the mid-1970s. The studio glass movement was gaining momentum elsewhere. But Jolley was already operating by his own logic. “I was raised close by,” he says. “Knox County’s zoning laws were more flexible, and I still think Knoxville is a good place to live.”

He found a building, installed furnaces, and opened his studio in 1975. What began as a practical decision slowly became a defining one. Over five decades, Jolley has maintained a working hot shop, produced an extraordinary body of work, and built an international reputation—while East Tennessee’s arts community grew and matured around him.

His studio, located in West Knox County, has welcomed museum curators, collectors, students, and schoolchildren alike. And while his work has traveled globally, he has always returned to the same place to make it.

Finding a Voice in Glass

Ask Jolley what drives him, and he doesn’t talk about recognition. He talks about process.

“When you’re young, you worry about finding your voice,” he says. “As you get older, it becomes natural. It’s like breathing.”

Glass suits that evolution. It demands speed and precision but rewards patience and intuition. Jolley describes working with it as a kind of choreography—fire, movement, intellect, and teamwork.

Watching him work does feels like observing a well-rehearsed dance. Assistants move in sync, transferring pieces from furnace to bench to pipe, where

a single mistake can end a piece instantly.

“What can go wrong?” he repeats a question he’s heard a thousand times. “This, this, this, and this—and the answer to all of it is yes.” He explains “it’s just like anything else.” Accumulating a creative knowledge through hand and eye skills and mental concentration is the way to minimize these outcomes.

Early in his career, Jolley drew inspiration from Henri Matisse, creating blue-line works in glass that explored how subtle shifts in line could alter expression and mood. Over time, his work became increasingly sculptural and figurative—elongated bodies, stacked forms, and iconic heads that feel both ancient and contemporary.

Asked about his favorite piece, he doesn’t hesitate: “The one I haven’t made yet.” Respecting the past matters, he says, but dwelling there too long can stop you from moving forward.

Birds, Busts, and the Human Narrative

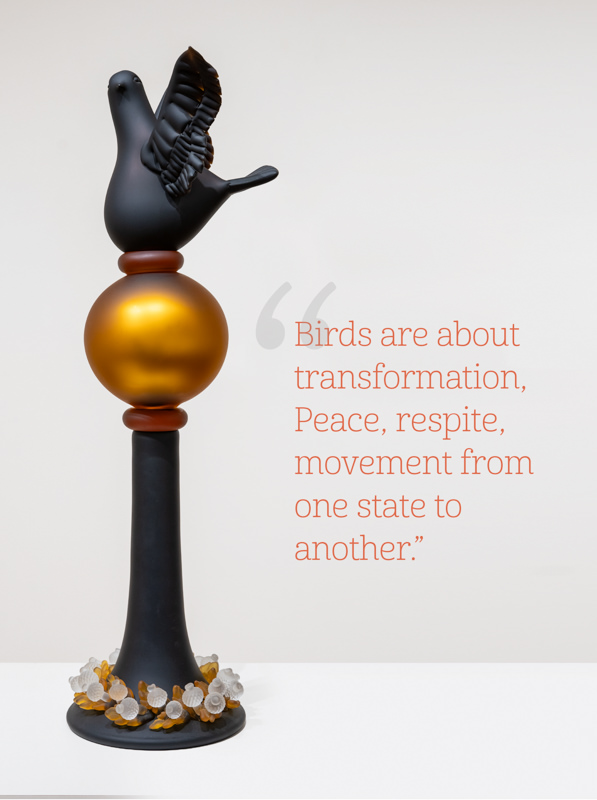

Certain themes repeat themselves in Jolley’s work the way certain chords show up in a songwriter’s catalog. Birds appear again and again—balanced on heads, caught mid-flight, hovering in flocks. “Birds are peace, respite, transformation.”

The human bust is another recurring form. For Jolley, the face is the most psychologically charged part of the body—the place where identity, emotion, and story reside. Working figuratively in glass is difficult, but that challenge keeps him engaged.

For years, he worked to soften glass’s natural shine, using acid etching to create matte surfaces that read more like stone or bronze. More recently, he’s incorporated gold and silver foils and drawn from Venetian techniques such as scavo, giving pieces a sense of age and depth.

He’s also known for improvisation—some of Jolley’s approaches are inspired by ceramics and even cake decorating. “It’s very spontaneous,” he says, “capturing this one moment of time with this visceral quality of material.”

A Landmark for Knoxville

If Jolley has created a single work that defines his relationship with Knoxville, it is Cycle of Life: Within the Power of Dreams and the Wonder of Infinity at the Knoxville Museum of Art.

Suspended in the museum’s great hall, the massive glass-and-steel installation stretches nearly 100 feet and rises 12 feet high. Figures move through stages that suggest birth, discovery, turbulence, and transcendence, surrounded by swirling forms that feel at once atomic and cosmic.

For the museum, the piece became a defining statement. For the city, it stands as a reflection of ambition rooted in place. “The museum project is fabulous because of its scale and scope,” Jolley says. “I think it helped define the institution.” It also quietly affirmed Jolley’s role as one of Knoxville’s most influential cultural figures.

Giving Back and Teaching Forward

Jolley credits mentors and patrons for shaping not only his career but his sense of responsibility to the community. He learned early that success meant participation, not isolation.

That belief has translated into decades of teaching, mentoring, and quiet philanthropy. He’s welcomed groups from Community School of the Arts, worked with students from Beaumont, supported nonprofit organizations, donating work or proceeds when it can make a difference.

During the pandemic, Jolley and his wife, glass artist Tommie Rush, used one of his works as the centerpiece of a fundraising effort to address hunger in Knoxville. Rather than simply donating, they used art as leverage—raising far more than a single check could accomplish. “If you can use what you do as a multiplier, it becomes much more positive,” he says.

For Jolley, exposing kids to the studio isn’t about creating future artists. It’s about widening perspective. “You’re showing them that there’s a bigger world out there,” he says. “If you do it right, you can give them a very good sense of self-worth in a start-to-finish amount of time.”

Partnership and Shared Curiosity

Jolley’s story is inseparable from that of Rush. Trained as a ceramicist and later an accomplished glass artist, Rush brings her own distinct voice to the medium. Together, they share not just a life, but

a decades-long conversation about materials, color, and form. Jolley delights in tracing connections across disciplines—from Roman frescoes to modern glass chemistry—seeing all material traditions as part of a shared human impulse to shape meaning from raw elements.

On Fame and the Long Game

When Jolley speaks to younger artists and students, he’s struck by the questions they ask. Referencing a recent lecture “they weren’t asking, ‘How do you do this technically?’ They were asking, ‘When did you become famous and how were you discovered?’”

A mentor once told him that no single show, gallery, or collector would make or break him. The only real requirement was persistence. “If you want to be an artist, you have to continue to work,” Jolley says. “It’s that simple.” And while he understands the realities of sustaining a studio, beneath the logistics is a stubbornly straightforward philosophy: show up, make the next piece, keep learning.

Asked years ago about five- or ten-year plans, his answer never changed. “I don’t know,” he’d say. “But I’ll be there.”

Fifty Years In

Fifty years after opening his studio, Jolley is still at the bench. The equipment is better, the projects larger, the résumé longer—but the essentials remain unchanged. The heat is intense. The risk is real. The reward is opening the annealer and seeing something whole where there was once only molten possibility.

From Oak Ridge to Knoxville, from a freshman elective to international acclaim, Richard Jolley has built a life defined by patience, curiosity, and commitment to place. “I feel lucky,” he says. After fifty years of fire and glass, Knoxville is lucky, too.