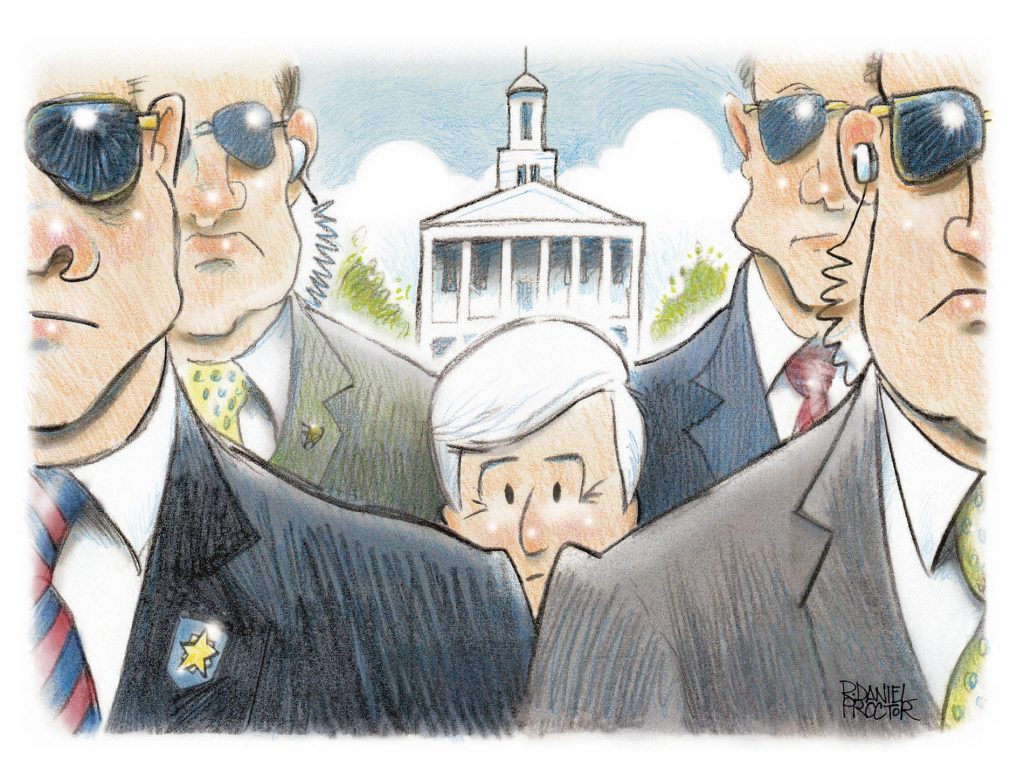

Additional security measures can work, but can they sometimes be too much?

Security is as security doesn’t. I wasn’t a danger to President Ronald Reagan, but based on where I was standing, the complexity of security apparatus guarding Reagan on his March 15, 1982, Nashville visit proved the validity of Starship Enterprise Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott’s observation that, “The more they overthink the plumbing, the easier it is to stop up the drain.”

Security is sometimes legitimate. However, sometimes it’s the result of asking a security consultant if a government building or a business needs more security. What do you expect them to say? It’s like asking a University of Tennessee football fan who can’t get a ticket if Neyland Stadium needs more seats. Often, security’s main accomplishment is to inconvenience people who obey the law and who pose no threat. But pouring on additional layers of security is at least “doing something,” even if it doesn’t do much of anything. A person with evil intent will find a way to do evil things.

A case in point about security complexity: President Reagan visited Nashville almost exactly a year after the assassination attempt on him in March 1981, outside the Washington Hilton Hotel, a mere 1.5 miles from the White House. He was wounded when a bullet hit him after ricocheting off his limousine. A year later, the president came to Tennessee to address a joint Tennessee General Assembly session. Nashville was on full alert: the only thing not done to protect Reagan was to clear downtown Nashville of people. Streets around the Capitol building were barricaded, manned by police officers; pedestrians and cars were prohibited. Secret Service agents were ubiquitous, talking into microphones on their wrists. Sharpshooters, observers—or both—were atop buildings around the Capitol.

Access to the House of Representatives chamber, where the president was speaking, was tightly controlled. As a state spokesman, I watched Reagan’s speech on a TV in the governor’s press secretary’s office. Shortly before the speech ended, I walked down the first-floor Capitol hallway, past the governor’s office, down the south steps, and onto Charlotte Avenue, the main street that passes the Capitol.

I stopped about 30 feet from the front of the presidential limousine. I was wearing a suit with a State of Tennessee pin in my lapel. When a president travels, the Secret Service issues pins (which change every day) showing that the wearer is authorized to be in the president’s proximity. I didn’t have a pin, but I was standing only a few feet from Reagan’s car—and no one asked me anything.

When Reagan’s speech ended, security people emerged from the Capitol like ants from an anthill. They took up positions around where the president would exit onto Charlotte Avenue from The Tunnel, a walkway that runs beneath the Capitol Building and opens onto the street. The limousine was about 20 feet from the Tunnel door. People in the presidential motorcade were getting into their vehicles. And I just stood there. A man walked up on my right side. Assuming he was part of the elaborate security precautions, I leaned over and asked, “Is it OK if I stand here?” He said, “I don’t care where you stand.” Then, I recognized him: it was Nelson Benton of CBS News.

A few moments later, I could feel the tension increase: the president was coming. When the Tunnel door opened, Reagan came out. Aside from state employees watching from Legislative Plaza War Memorial Building office windows, no one was around except people in the motorcade. And me. And I just stood there. The president’s car departed, with me watching from my unanticipated, up-close vantage point.

Another example: When George W. Bush first ran for president, he made a visit to South-Doyle High School. To enter the gymnasium, everyone had to go through one of several metal detectors: the lines were daunting. As I was there in my capacity as WATE-TV political analyst, I went to the back of the building, the journalists’ entrance. A friend’s son with an interest in politics accompanied me.

We stood for a moment and watched Secret Service agents and police officers search the camera bags of TV crews and inspect radio reporters’ recording devices. We then walked through the door into the building, the agent at the door simply nodding as we passed. No metal detector, no emptied pockets, no nothing.

Each of these experiences represents security slip-ups. Because they happen. And too often, acts of “protection” separate the public from their government. For example, walling off the City County Building parking garage from public use doesn’t make the building more secure; to truly do that it would be necessary to close the streets around the building and set up checkpoints for any vehicles entering the CCB safety zone. Even then, there’s no certainty. But one thing’s certain: closing the garage to the public provides government employees with low-cost parking.

I was once talking to a judge about the CCB’s security arrangements. He said, “We need them. We get threats.” I said, “So you never leave the building, never go to lunch, you don’t go home and never go out in the evenings?” He stared at me. He didn’t know what to say. Because he knew that someone intent on doing evil will find a way.

Unquestionably, if security at government buildings returned to the time when a free people could enter buildings freely, there would be accusations, recriminations, and lawsuits. That, principally, is why before they enter a building, Americans have to prove they’re not potential criminals. But security for the sake of “doing something” typically affects only well-intentioned citizens. And, as experience has shown me, the more security officials overthink security, the easier it can be to be seen, but not seen.

Comments are closed.