Service as a U.S. Marine helped Bob Sparks rise from rural Appalachia to a life of business and personal success

When Bob Sparks enlisted in the U.S. Marines in 1961, the 17-year-old out of southwest Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains quickly discovered that he was better equipped for basic training than many of his fellow recruits at Parris Island, South Carolina.

“Having grown up outside, hunting, trapping, fishing, farming—it was a big benefit,” says Sparks, seated at a table in his property-management office off Northshore Drive in the Rocky Hill area of Knoxville. Several military awards and mementos occupy a nearby shelf. “I had a lot of the natural skills already, to be able to shoot pistols and rifles and become known as an expert marksman.”

Fellow enlistees and officers alike marveled at how quickly Sparks excelled. His skills had not resulted from mere hobbies or weekend pursuits; they had been the key to his survival as a boy and a teen.

Born in 1944, Bobby Eugene Sparks was the seventh of 11 siblings in rural Tazewell County, Virginia, (not the Tazewell we’re familiar with in East Tennessee). The family looked after each other and “produced about 85 percent of everything we ate or used,” Sparks says. His grandparents owned three houses side by side, one of which was home to the elder couple; one to an uncle, aunt, and four cousins; and the other to Sparks’s brood. There was no running water, no indoor plumbing, no heat on cold nights other than what the stove could generate.

Sparks’s father was a coal miner, “when he could get work,” his mother a hard-working restaurant cook. “We had kind of a sparse upbringing,” Sparks says. “We farmed enough to can and preserve several hundred jars of food every fall, which we needed just to get us through the winter with that many kids. I guess we were poor, but we didn’t know we were poor.”

The youngsters roamed the woods hunting wild game with small arms and fishing for supper. They sometimes ran across a moonshine still or two tucked behind a hill or hollow.

In many ways, such a boyhood was idyllic. But when Sparks was 11 years old, tragedy struck. His mother suffered a massive heart attack in the middle of the night, and suddenly she was gone. The loss was devastating. Sparks recalls that his siblings helped make life bearable as they worked hard to continue providing for the family’s needs.

As Sparks’ tale unfolds, similarities to the book Rocket Boys (and its Knoxville-connected film, October Sky) come to mind. Like Homer Hickam Jr., Sparks seemed destined for a job deep in the coal mines after high school. He made a patriotic choice to circumvent that inevitability.

“I left school my junior year to join the military,” he says. “I went in 16 days after my 17th birthday. It was a great opportunity to get away from where I grew up because it was coal, just coal. Mining was the only business we had back then.” Sparks had no interest in following his father and several of his brothers into the mines. (As a teen, he had also helped several other siblings travel around constructing Jim Walter modular homes.)

Sparks says he “wanted to serve the country and make it a better place, which I think we did.” He opted for the Marines “to be in the front. They were the tip of the spear, always the first to go in. I wanted to be part of a solution, to get something done.”

When Sparks joined in 1961, tensions in Southeast Asia were simmering toward what would become America’s engagement in Vietnam, which began in earnest when the first Marines landed on the beaches near Da Nang in March of 1965. Sparks would not be called to serve there; instead, he would be stationed in Okinawa and train troops who were sent from there into the fray of Vietnam.

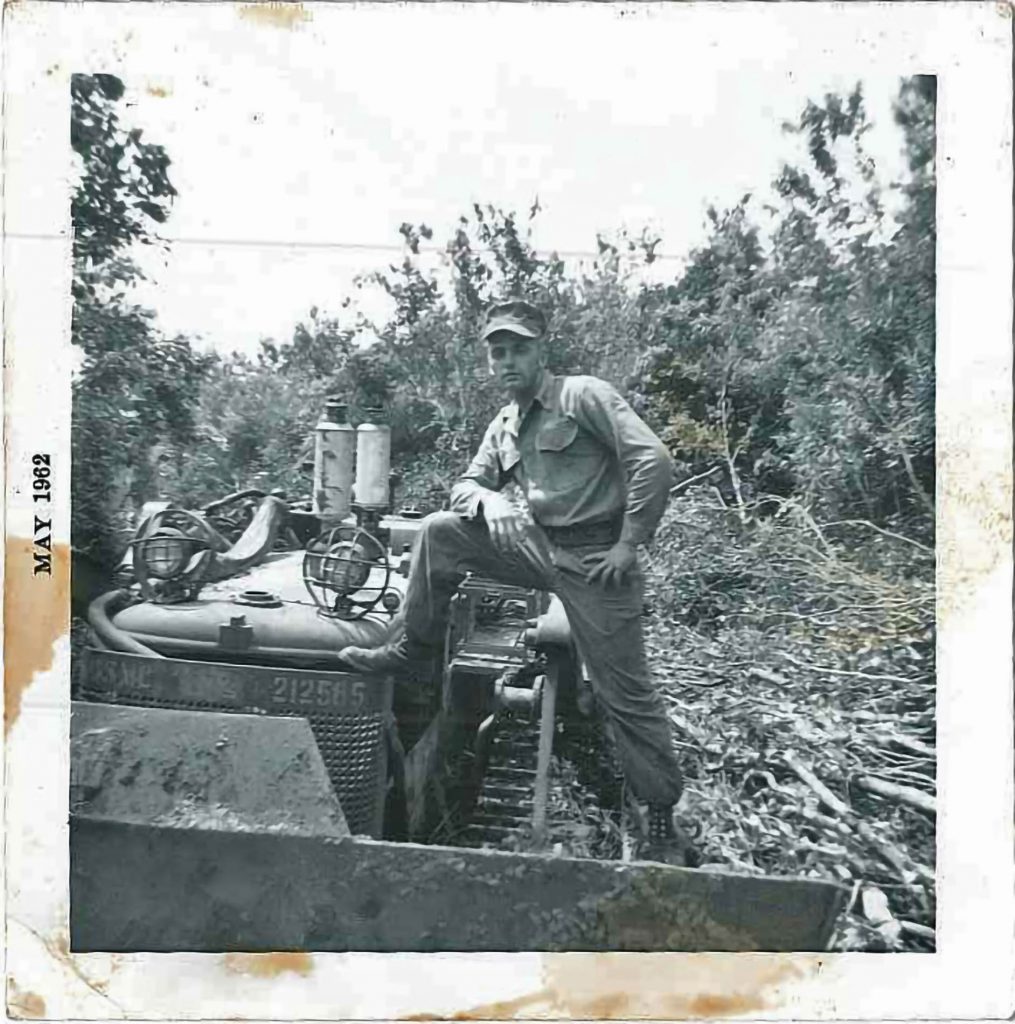

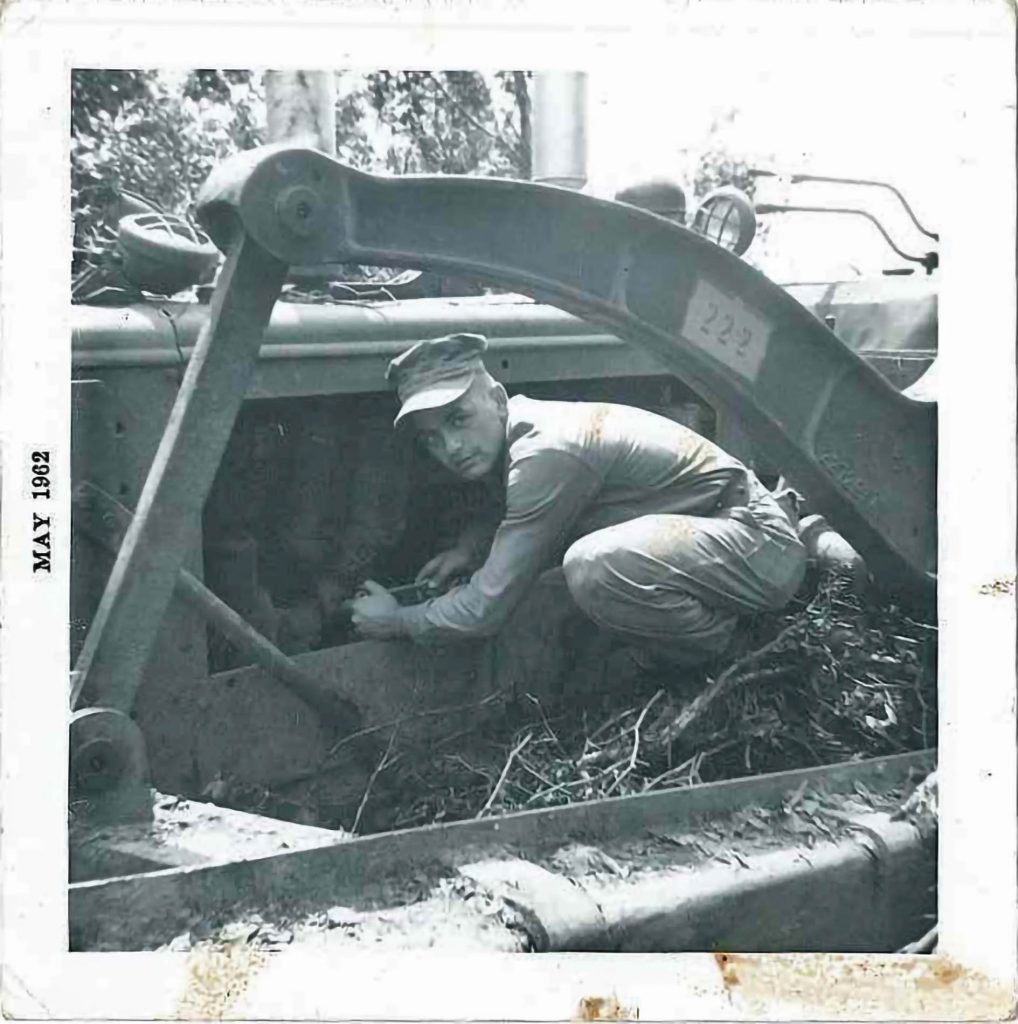

After 16 weeks of basic and intensive training at Parris Island, Sparks, a combat engineer, was assigned to help build an airstrip at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point in North Carolina. He was later transferred to California, where he served in the 1st, 3rd, and 5th Marine divisions, and then shipped out to Okinawa for a year-and-a-half tour. There he ran the armory, trained fellow Marines, and, in his free time, worked to become a 2nd-degree black belt in karate. Later, he was stationed in Puerto Rico, where he helped build an airbase.

As he talks about his path through the military, Sparks is low-key and easygoing—until the subject of the training comes up. “My ego says that I was better to train people than I was to be shot at, and I guess that saved more people by preparing them for battle.”

Asked about some of the Marines he trained who fought in Vietnam, Sparks pauses for a few moments. “I’ve got a lot of friends whose names are on that wall,” he says quietly, referring to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial that opened in Washington, D.C., in 1982.

And then he looks down, reflects silently for a minute that stretches into two, and excuses himself for a break. When he returns, he sits back down and says, “Sometimes I have some memories, I guess.”

After he was honorably discharged in 1967, having achieved the rank of Lance Corporal, Sparks returned home to southwest Virginia for a short time to “sort of clear my head,” he recalls. Knowing and training fellow Marines who had died in combat weighed heavily on him.

Six years had passed since his enlistment. He was 23. He walked along the creek beside his family’s home, the same creek from which he had carried water for bathing. He crossed a narrow bridge and meandered along another creek where he had fished to help feed his family. He walked through the woods where he had hunted and trapped game. He lingered at his grandmother’s well, where the Sparks children had trekked to fetch water and carry it back to the house for drinking and cooking.

He let the familiar environs and the soft mountain air ease away some of the horrors of war. And when he was ready, he turned the page to a new chapter of his life.

With his hardscrabble early years and toughness as a Marine, Sparks wound up working in collections, tracking down loan payments, sometimes in rough parts of towns. “I guess I wasn’t smart enough not to go into areas that I shouldn’t have,” he says.

Later his work in financial services took him from Virginia to Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. “I was, what they called, ‘the collector’ because the company I worked for would lend money to smaller companies. And if they got delinquent, I would travel to those offices, usually with a letter from the president of the company that said, ‘You’re fired.’ I would take their keys. Sometimes we retained some of their staff, and sometimes we’d fire the whole office. And then I would recruit people and train them to take over that office. I did that for several years.”

He then ventured to Indiana where he finished college at Ball State University—the last of five schools he had attended during and after his military service after earning his G.E.D., thanks in large part to the G.I. Bill. His degree was in teaching. But in the early 1970s, Sparks purchased a real estate firm, then a tech company, and grew his knowledge as a businessman.

Along the way, he began handling leases for outdoor-advertising companies. He met and married his second wife, Sally, in Kentucky, in 1988. A year later, Lamar Advertising Co. asked Sparks to head up its Knoxville office, so the couple moved south. Sparks retired from that role in 1998. In 2002, he bought a Century 21 franchise. “We took a company that was producing $200,000 in annual revenue and grew it to $1.3 million,” he says. They sold it in 2017.

Today, Sparks works in property management and shares space with Sally, an accomplished Knoxville-area Realtor®. Some say that Sparks bears a resemblance to the Dos Equis “Most Interesting Man in the World,” and it’s fair to say that Sparks has navigated his share of interesting twists and turns.

In his three-plus decades in Knoxville, Sparks has become deeply involved in church, civic, and charitable efforts. “The atmosphere in Knoxville is pretty relaxed,” he says. “A lot of people want to help. We’ve served on several boards, and volunteers are easy to get. People want to be your friends here, so it’s a good place to live.” Making it even sweeter: Sparks’s three children from a previous marriage all live in Knoxville. “All of my grandkids are within five miles of me.”

Sparks is a card-carrying member of a gang dubbed the ROMEOs—Retired Old Men Eating Out—who often gather at Mimi’s Café in Turkey Creek and at other spots to share stories, jokes, memories, and friendship. Not all, but many, are fellow Marines or other military veterans. The fellowship they share helps Sparks remember the sacrifices they and many of their brothers and sisters have made for the nation they love.

“I’m very, very proud that I had the opportunity to serve,” he says. “Yes, sir. I’m very proud that I did my part to take care of our country. And it made me a better person for sure, because it made me more responsible, more in tune with other people’s needs than my own.”

Serving was an honor, he says. “It gave me an opportunity to grow, with the discipline that they gave me. I think it’s a wonderful opportunity for young people to go into the service and figure out what they want to do in life.”

Becoming a U.S. Marine carries with it “the pride of the uniform, and training that made you what you are. We were the spear point; that’s the purpose of the Marines.”

Sparks looks back fondly on the education he received and the confidence the military instilled in him. “I was privileged to sit at the table with ranking officers and be part of things that gave me a lot of satisfaction, that I was elevated from a poor boy in Appalachia up to those important places.”

As the conversation winds down, Sparks apologizes for the emotion he had displayed earlier. Not at all, he is told. He has no reason to apologize. He is human. He lost friends who gave their last full measure of devotion. He has more than earned any feelings he might experience, and every tear that might fall—even if they were to fill the buckets he once toted to his grandma’s well and to those bubbling creeks of his wild, mountain youth.

Comments are closed.