A long-awaited voyage through a vital trade waterway opens the door to the story of a diplomat

Seeing and traveling through the Panama Canal has been on my bucket list for decades. Now that my dear bride has finally given her permission for me to sort of retire from the legal profession, I developed a plan to persuade her to join me for the trip. Booking a luxury cruise from Florida did the trick. So, in early December of 2024 we left Fort Lauderdale and meandered through the Caribbean Sea until our ship got in line to pass from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the iconic canal. Along the way through the Caribbean, we had made some interesting excursions—Belize and Costa Rica for example—but the real fascinations for me (a sign of the aging process) were the several lectures and videos setting out the background of just how the canal came to pass. A central figure in its history was a name unfamiliar to me—a 19th century Frenchman by the name of Ferdinand de Lesseps.

“The higher you go, the harder you fall” is the English translation of plus vous montez haut, plus ils tombent fort. This common phrase is believed to have originated in France and could be applied to the life and legacy of de Lesseps. This man had enjoyed a distinguished career in diplomacy and had established many important international relationships when he decided to undertake the monumental task of leading the effort to construct the Suez Canal, a project which would facilitate trade by connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. This was not an entirely novel idea.

In ancient times, Egyptian pharaohs had shortened the water route to the Middle East by building moderately-sized canals from the Red Sea to the Nile River—a waterway which ultimately led to the Mediterranean. Some 3,000 years later, Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Egypt and then sent surveyors to determine the feasibility of connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea, an inlet of the Indian Ocean. Upon concluding that there was a differential of 30 feet in altitude between the two bodies of water, Napoleon’s surveyors recommended against the project, frustrating his plans for even more worlds to conquer. As it turned out, however, his surveyors were wrong.

Fifty years later, French engineer Louis Maurice Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds determined that there was no difference in the levels of the two bodies of water. Because this finding would substantially reduce the projected expense of construction, de Lesseps was inspired to form the Suez Canal Company. With a 99-year lease of Egyptian territory, the company received what was then an amount equal to $50 million in private investments.

The work, which began in 1854, involved 120 miles in length and required the removal of 75 million cubic meters of sand. When the Suez opened on November 17, 1869, the actual cost had become twice the original estimate. Despite the cost overruns, de Lesseps became a hero in France, even though his country ultimately had to acquire 56 percent of the stock and Great Britain the remaining 44 percent to finish the job. Each country prospered. World shipping trade increased dramatically by use of the new route.

With this history of success, France soon voted to create the Panama Canal Company with the aim of connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America. Of course, de Lesseps was offered the presidency of the project. The hope was to cut thousands of miles of time and expense for ships then required to travel around the southern tip of South America. As with the Suez, de Lesseps’s plan was to avoid the enormous construction costs of locks by excavating through the challenging topography in Panama. In 1880, he traveled to New York, Boston, and other United States cities to attract investors for the project. In Washington, D.C., he met with President Rutherford B. Hayes to discuss his plan and testified before Congress.

De Lesseps had estimated a cost at 658 million francs—equivalent to more than $130 million in those days—and predicted eight years to finish. After enlisting the requisite number of investors, he began construction. The project, however, encountered significant problems in implementing the design. So, de Lesseps enlisted the aid of Gustave Eiffel, a highly regarded French civil engineer, contractor, and entrepreneur. This is the same Gustave Eiffel who had engineered the interior of the Statue of Liberty for Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the sculptor who designed the iconic statue, and who, by that time, had presented his proposal to build a tower which would bear his name for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris.

Even with the help of Eiffel, disaster struck the Panama project, financial and otherwise. Thousands of workers had died of malaria and yellow fever. Moreover, the rainfall in the tropics saturated the soil. The deep cuts in the ground resulted in landslides, destroying equipment and taking even more lives. Costs skyrocketed out of control. There were no new investors. In 1888, only two years after de Lesseps had been chosen to present the Statue of Liberty on behalf of France, and less than a year before the opening of the World’s Fair in Paris, the Panama Canal Company filed bankruptcy. De Lesseps had failed.

An investigation established that some 150 French deputies had been bribed to vote for financial aid to the company. De Lesseps, and even Eiffel, who had been hired only as a contractor, were charged, tried, and convicted of conspiracy and fraud. In 1894, the court fined each of the men and imposed two-year prison sentences. Their reputations suffered even though, on appeal, a higher court ruled that a technicality—the three-year statute of limitations—barred their convictions. Eiffel, embarrassed by his notoriety, removed his name from the company he had founded. In 1894, de Lesseps died, his dreams for Panama unfulfilled.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt rescued the project. He made the canal a priority, persuading Congress to buy the assets of the bankrupt French company and contracting with the newly created Panamanian government for the United States to take over construction. After negotiating an especially favorable deal with Panama’s new leadership, America succeeded where de Lesseps had failed.

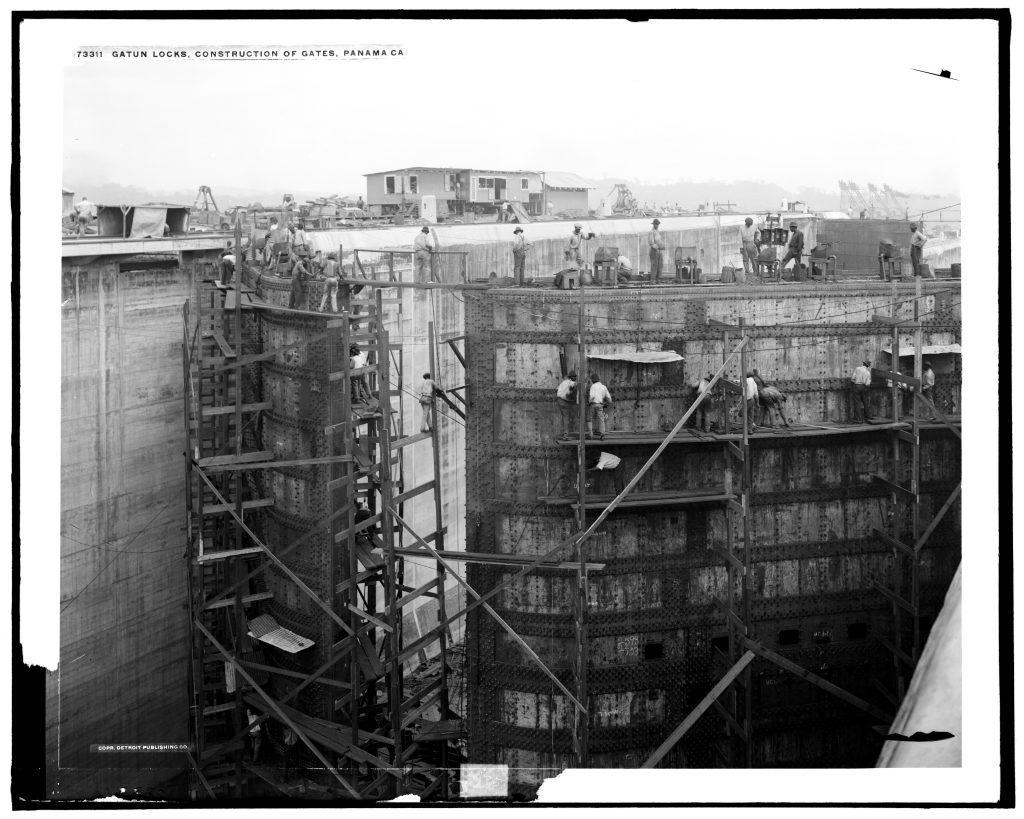

First, the U.S. designers abandoned the sea-level approach, opting instead for a lock-controlled system, one which would usher ships up and down the canal as necessary, thereby avoiding much of the hazardous digging through Panama’s rough, wet terrain. Second, medical science discovered the role of mosquitoes in the spread of tropical diseases. The control of these insects greatly improved the health of its workers, limiting the cases of malaria and yellow fever during the lengthy period of construction. More than a decade passed before completion.

On April 14, 1914, the first ship to be able to travel the entire 51-mile distance was, ironically, a French crane boat called the Alexandre La Valley. The canal, however, could not be opened to commercial traffic until August, only days after the first shots were fired in Europe, triggering World War I. The price tag for the canal came to $375 million, $23 million less than originally estimated. That sum included $40 million to the bankrupt French for the benefit of its creditors, and $10 million to Panama for property rights. Despite the huge economic benefits to the U.S., there was a tragic downside. Even with the precautionary measures, employee deaths for the project numbered more than 5,500 from all nationalities, at least 350 of whom were Americans.

During the First World War, this country was able to control access to the canal. Its primary use in those years was to more quickly move military troops and supplies. After the armistice, this country increased its status in global trade. To illustrate, the new shortcut meant that ships sailing from New York to San Francisco saved 7,800 miles in distance and as much as a month in travel time. Years later, when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. joined the Allies in World War II and fortified its military control of the canal, sending 65,000 troops to protect its strategic asset.

On January 1, 2000, after almost 86 years of rule, the U.S. yielded full administration and management responsibilities to the Panama Canal Authority. That, of course, is another story.

Comments are closed.