Former Air Force leader and Vietnam veteran Jim O’Brien gives back to his adopted Knoxville community

When 591 American prisoners of war arrived back on U.S. soil from Vietnam in early 1973, Jim O’Brien was midway through his studies at the University of Notre Dame, but the chill of winter in South Bend, Indiana, stood no chance against the warmth the young man felt as he watched on TV while veteran after veteran deplaned in Hawaii.

Just a few short years earlier, O’Brien had briefed and debriefed many of the Air Force pilots whose missions put them in harm’s way, some of whom would be captured and held as POWs. Now, tearful reunions with wives, children, and parents on the tarmac stirred the hearts of many war-weary Americans.

“That was quite a celebration for the men, their families, and all who saw it, but for those of us in the war who had lost friends, it was especially joyful,” O’Brien recalls from his home in West Knoxville, his typically upbeat, energetic tone tempered by a momentarily somber note. “Watching them embracing the families that had been flown in to meet them, it meant an awful lot.”

“To See Them Coming Home Alive…”

From July 1968 to July 1969, O’Brien had served a tour of duty as an Air Force intelligence officer, providing vital information to pilots who flew missions into and out of Vietnam as they sought to locate and take out enemy surface-to-air-missile (SAM) sites. Some of those pilots would be shot down, taken prisoner, and held in the infamous Hỏa Lò Prison, more widely known as the “Hanoi Hilton” where scores of POWs including the late Senator John McCain and Vice Admiral James Stockdale were held and tortured.

“I have a lot of friends whose names are on that wall [of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial] in Washington, so to see those men coming home alive…” O’Brien pauses, clearly moved.

Later in 1973, he would receive a related blessing in the form of a new friend, Tom Moe, who had been one of those American POWs returning home, and who was now enrolled at Notre Dame. Meeting Moe on campus and talking with him about his experiences served to bring some healing to O’Brien.

“He had been incarcerated at the Hanoi Hilton for six years,” O’Brien says. “He could have been one of my guys. After a much-needed and well-deserved leave with his family, he had come to college. The stories he told and the times we spent together—that was cathartic for me.”

After completing his master’s in government with a specialization in Soviet-East European Affairs, O’Brien would continue a surprisingly lengthy and decorated U.S. Air Force career, culminating in the rank of Colonel and leading some 10,000 intelligence staff across the globe.

“I had expected to do my four years and then go to college on the G.I. Bill and be done, but 27 years later I retired on the same parade field where I had been commissioned,” he says with a chuckle. “I was blessed with a fabulous career.”

When he opted to retire from the Air Force in 1994, O’Brien had moved some 23 times in 27 years; the last 10 or so years had included his wife, Diane. “She earned her PhD in packing and unpacking boxes,” O’Brien quips. The couple was ready to put down roots for their daughter, Meghan, who was then 8.

As it turned out, the last stop on their far-flung journey would be East Tennessee. “God was saving Knoxville for the O’Briens,” Jim says today with his trademark wide smile.

From Roxbury Guy to Pentagon Man

There had been no early indication O’Brien would end up going career military with influence in the halls of the Pentagon and beyond. Born in 1945 in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, near Boston, he graduated from Needham High School and earned a history degree from nearby Stonehill College. (He had enrolled briefly in a diocesan seminary before going to college, but says he realized “I liked women too much” to become a priest.)

It was now 1967. With designs on pursuing a master’s and PhD to become a university professor, O’Brien was told by the local draft board that his number would likely come up that fall and that a deferment for higher education in “softer” fields was highly unlikely. In a preemptive move, he enlisted in the Air Force and was commissioned in November 1967.

He would be assigned to the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing as an intelligence officer, and sent to Southeast Asia. During a yearlong tour that began in mid-1968, “my job was to brief the pilots, tell them what their targets were, where they could expect to find surface-to-air missiles, anything they needed to know to keep them safe. Once they got back [from flights into Vietnam], we would debrief: ‘Did you get the bombs on target? Were any missiles fired from an unexpected location?’ We would use any information gathered to prepare for the next day’s missions.”

It was perilous work. “The really unfortunate part of it, we were losing an airplane a week, shot down or crashing,” O’Brien says. “Sometimes we got the crews back, rescued, but all too often the pilot and the navigators, in some cases, were killed or captured and taken to Hanoi.”

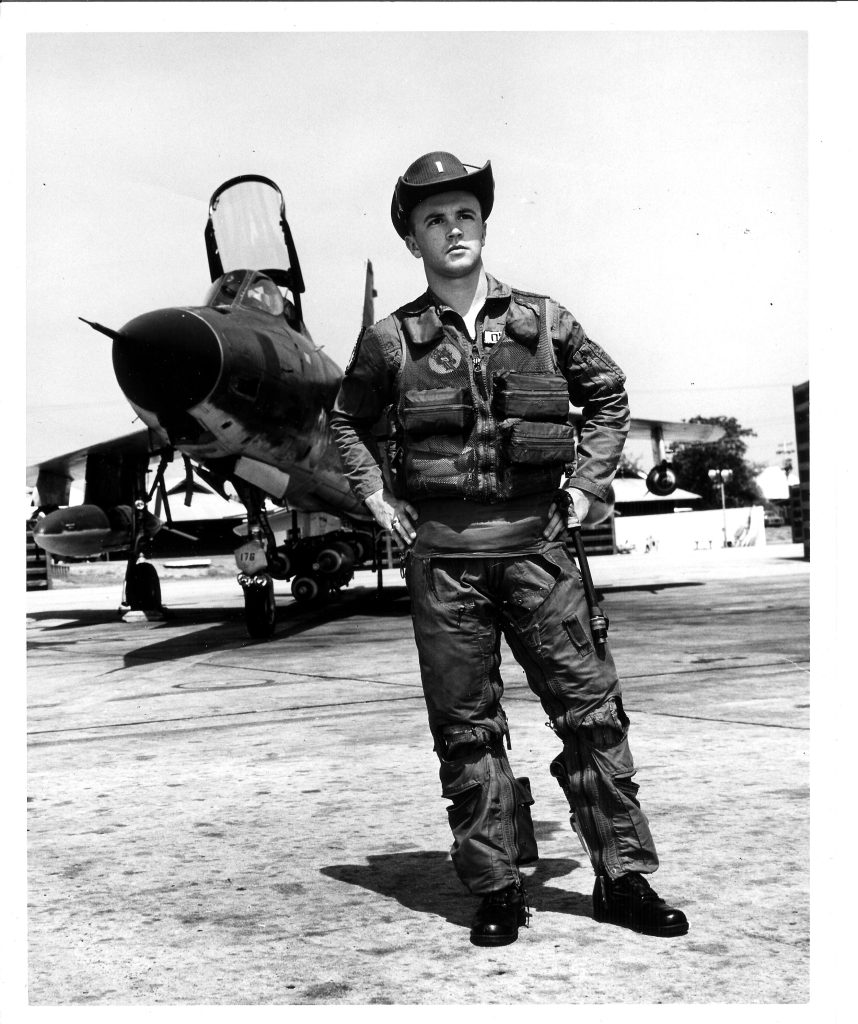

While most of his work was not directly in combat, O’Brien “did fly a few missions in the F-105” aircraft in an operation dubbed “Wild Weasel,” in which “we went trolling for North Vietnamese SAM sites” and to gather other vital details to share with pilot crews.

“It was one hell of a year,” he says of his tour.

Upon his return to the States in 1969, O’Brien was given options of where to be stationed and chose Europe, ending up at Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany. He advanced to the rank of Captain by 1972, the year he enrolled at Notre Dame. (While he became a lifelong Irish fan, O’Brien is quick to emphasize that as a transplant to our area—“I tell people I wasn’t born in Tennessee, I just got here as soon as I could”—he and Diane are dyed-in-the-wool Volunteer fans. “I cheer for Tennessee… until they play Notre Dame,” he concedes.)

His first assignment after South Bend, in 1975, was to the Pentagon in Air Force intelligence.

Thus began a gradual ascendency through the ranks that would include three stints in Nebraska—“nine Omaha winters was much more than enough,” he laughs; a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in 1976; meeting and dating Diane (they wed in 1982); six months in Rome, Italy, at the NATO Defense College; a return to the air staff at the Pentagon, working closely with the Joint Chiefs of Staff; a transfer to the Intelligence Committee Staff; and another promotion, this time to Colonel, at age 37— “which blew me away,” he says of having achieved the rank by that point in his career.

By 1989, after working in Omaha for the headquarters of Strategic Air Command (SAC), and then in San Angelo, Texas, home to an Air Force training center (Goodfellow), O’Brien was granted command of the 544th wing, with some 500 intelligence staff deployed. He would lead that wing through Operation Desert Storm in 1990 and into 1991.

A series of additional moves and assignments led to O’Brien commanding the newly established 67th Cyberspace Wing. “That was 10,000 people, all over the world, on every continent except Antarctica (by treaty),” he says. “We had a $500 million annual budget, and an HQ staff of 150 or so at Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio.”

General… or Dad?

The pressure-packed role suited O’Brien and his leadership skills well, but by 1994 he sensed that he had arrived at a crossroads. He remained on an advancement track to the top of the ranks, but looking back, he says, “I decided it was more important to be a dad than to become a general.”

And so the O’Briens relocated to Knoxville, arriving on July 4, 1994. Jim established a franchise business and began getting involved in the community. These days he operates a “one-man-band” travel business. Daughter Meghan, now 37, lives in Lenoir City with her husband, Jonathan, and daughter Lily. Her dad “had the honor of commissioning her into the Air Force Nurse Corp,” he says. Her service included six months in Afghanistan.

O’Brien’s volunteer positions have included leadership in Farragut Rotary, Bridge Refugee Services, and the Honor Air Flight program. He and Diane are also active members of Concord United Methodist Church.

One of his most cherished roles is with the Heroes & Horses program at Shangri-La Therapeutic Academy of Riding (STAR) in Lenoir City. O’Brien is effusive as he describes the program in vivid detail and shares stories of wounded warriors who have found hope and healing in the welcoming equestrian environment provided at STAR.

Among many relationships that he says have been meaningful, O’Brien speaks of a man named Mark, who narrowly survived a suicide bomber’s attack in Iraq. His wife, Sunny, fought to keep Mark on life support when hope seemed lost, and he lived. Now in his mid-30s with two sons, Mark deals with brain injuries and hearing loss. He has been riding horses at STAR for the past decade, and O’Brien beams when he expresses the positive difference he has witnessed firsthand in the fellow veteran’s life.

“There are so many others. Helping all of them has been very rewarding to me,” O’Brien says.

Others have noticed as well. On August 7, 2023, STAR honored O’Brien for his 13 years of “extraordinary fidelity and essential service” to Heroes & Horses at a ceremony attended by local elected officials.

As is typical with many other military veterans, he deflects praise and prefers to point toward “the real heroes” who have fought, been captured or wounded, battled to overcome post-war injuries or PTSD, or given their last full measure of devotion.

And as he reflects on his own lofty Air Force career and several eventful decades in the Knoxville area, O’Brien sums it up with one word: service.

“My whole life purpose, whether in business or in church or in the community or in the military—it’s why many folks join the ‘service’ in the first place—to be of service. My volunteer work, with STAR or Bridge or Rotary, has all been because of my desire to help other people. That’s what I do. That’s what Jesus expects of me, and I’m doing my best to comply.”

That desire has birthed an enduring dedication that has blessed not only the thousands of troops O’Brien influenced in the armed forces, but also the growing number of grateful veterans and other fellow East Tennesseans whose lives he continues to touch.

Comments are closed.