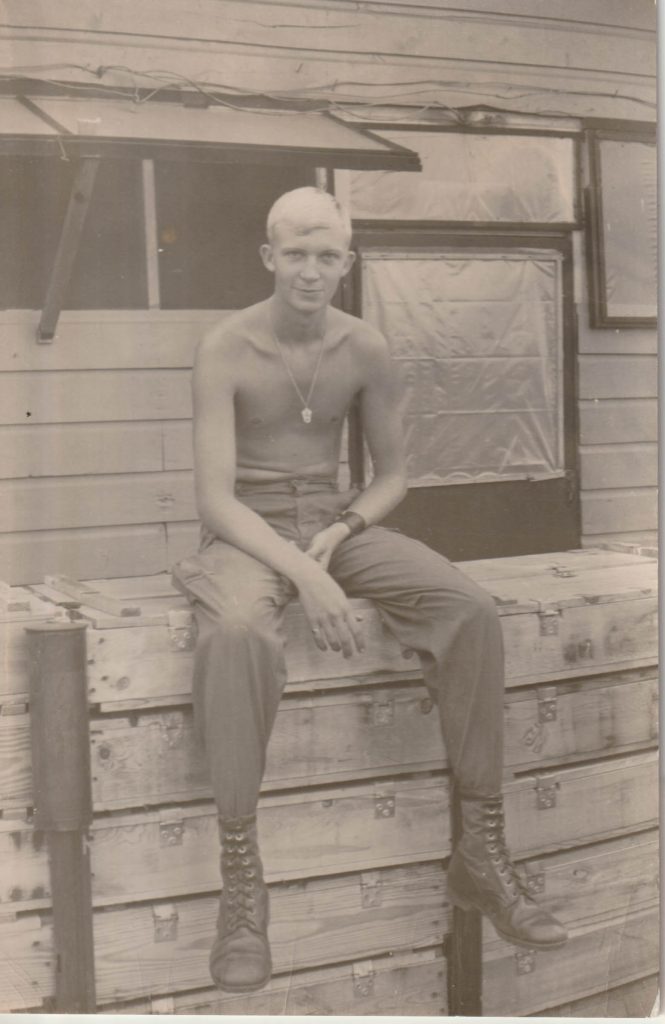

U.S. Army veteran Don Eklund reflects on his service amidst the flames of Vietnam

Some of the most vivid stories from the Vietnam era center on events long after the din of battle has faded. They reveal glimpses into a soldier’s character and leadership outside the context of steaming jungles, enemy attacks, and exploding mortars.

For Knoxville’s Don Eklund, one such story unfolded in an airport and on a flight in December of 1970, after he had completed his tour in Vietnam and was headed home to Tennessee.

Leaving the hot zones of Southeast Asia, Eklund was processed through Fort Lewis, Washington, in Tacoma, and transported to the airport for a nighttime connecting flight to St. Louis, before continuing on to Memphis. He was with a group of fellow U.S. Army soldiers taking similar journeys back to their respective hometowns.

“I was the oldest, 21, the rest of them were 20 or younger,” Eklund recalls. “We went into the lounge and ordered a round of drinks.” The server “starting checking IDs and found out most of the guys were not of age.” Eklund spoke up, vouching for the others, imploring her to bring them the spirits. She kindly but firmly refused.

“Do you mean,” Eklund said to her in a measured tone, “we can go over there and fight like hell to cover your ass, and come back here and they can’t order a drink?” She replied, “I’m sorry, but I can’t.”

After she left the group, Eklund told them, “It’s alright, boys, we’ll take care of this.” He bought a bottle of liquor and took it on the plane, he says, and “told everyone to order half a Coke.” Once airborne, he poured them a drink. When a flight attendant noticed and said to Eklund, “You’re not supposed to be doing that,” Eklund looked at her and replied, “Well ma’am, I just hate that,” as he continued pouring.

“I didn’t think it was right that after everything these boys had done fighting for their country, they couldn’t be served a drink,” he says. “We celebrated.” In St. Louis, the soldiers parted ways. After landing in Memphis, Eklund would continue east toward Knoxville. War protests in many parts of the U.S. were in full fervor at the time, but Eklund recalls that as he made his way home, “Everywhere I went, somebody offered to buy me a drink. No one accused me of being a baby killer.”

‘If I had stayed in school…’

Eklund was born February 8, 1948, in Memphis, but grew up in Lexington, Tennessee. His dad, Carl, worked for TVA and was transferred to the Knoxville area in the 1960s, where Don finished his junior and senior years at Karns High School (class of 1966).

Eklund enrolled at UT-Knoxville in the summer of 1966, but by the following spring he was “just about burnt out,” so he returned to Lexington to work for a friend’s father’s construction company. He recalls a vacation with his parents to his dad’s family in Wisconsin, then enrolling in a few courses at Jackson State Community College, where he also sold ladies’ shoes at Butler’s and got serious with a girl he had met in town.

In November 1968, the trajectory of his young adulthood took a sharp turn when he received a U.S. Army draft notice, ordering him to report the following month to Fort Campbell on the Tennessee-Kentucky border. He felt “a little regret, because if I had stayed in school and hadn’t played around, I probably would’ve missed the draft. It didn’t hurt me as bad as it hurt my parents. The one thing Dad wanted me to do was finish college.”

Granted a short leave during basic training, Eklund got married December 28, completed basic in February, and continued to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for advanced infantry training. By May 19, 1969, he had arrived at Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, in an inlet of the South China Sea. Back in the States, his daughter, Dawn, was born exactly one month later on June 19. “For a year, I got a lot of pictures but that was all,” he says.

‘Hotter than the devil…’

Eklund’s job—his military occupational specialty—was Indirect Fire Infantryman (11C), a.k.a. 11 Charlie, where he would work the M2 4.2-inch mortar gun. After a week at Bien Hoa Air Base not far from Ho Chi Minh, Eklund’s assigned duty station was Landing Zone Betty, or Phan Thiết, located on the coast. “It was hotter than the devil, and there was nothing but sand,” he says. LZ Betty was home to Task Force South of I Field Force, a corps-level command of the U.S. Army.

As is the case with many military veterans, Eklund’s fondest memories involve fellow soldiers. For example: “At LZ Betty my squad leader had about a month left in-country, but he took me under his wing and taught me the ropes—all about the gun I was going to be on, what to look for, how to hear incoming rounds,” Eklund says. “You could actually hear the weapons they fired, and you had about 20 or 30 seconds to take cover.”

Eklund “got the grunt details at first,” on proper placement, getting rounds, and preparing them. “Then you learned how to use the gun, and then how to remove a hang fire.” He explains, “If you drop a round down the tube and it doesn’t come out, you have to take the gun apart, reach down the barrel, and pull that round out. Nobody wanted to do that! The reason they wanted me to,” he says with a laugh, “was because I was 6-foot-3 and had longer arms than anybody.”

His height also led to a “strange experience” when Eklund was ordered to travel north to take part as a flag bearer in a change-of-command ceremony, in which one general replaces another. “They made sure we had starched fatigues and polished boots. It was a big whoop-de-do,” he says. “Then they flew us back, and I was back on the mortars.”

On one occasion when LZ Betty came under heavy mortar and rocket fire, Viet Cong troops penetrated the perimeter, resulting in an intense effort to fight off the attack. “The night we got hit, I was a squad leader, and we were on the gun,” Eklund says. “We had some troops try to get through the wire, and all hell broke loose. We had a fire mission, and we fired the whole time. The barrel would get so hot you could light a cigarette off it. That was quite a night.”

Late that fall, Eklund’s squad was assigned to Landing Zone Uplift at Deo Nhong Pass north of Phù Mỹ. In December, his squad was one of two that went to Firebase Christmas in the Central Highlands to provide cover fire for troops in the surrounding areas. “We were way up on a mountain. It was so different up there—it rained 28 of the 31 days, and it was cold.”

‘It felt like an earthquake…’

As his tour progressed, Eklund’s squad was attached to the 506th Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division, and to “The Herd,” the 173rd Airborne Brigade, a special ops task force containing elements of the 10th Mountain Division and the 10th Special Forces Group.

Eklund’s squad was tasked with providing mortar fire for ground troops. In the Central Highlands, he recalls, “we were on each side of a big mountain that was honeycombed with caverns. We fired and fired and fired and fired. And when we weren’t firing, jets were dropping napalm or high explosives on it.

“We had our moments. One night it felt like an earthquake. [The U.S.] had a B-52 bomber drop. You felt it, but you never saw the planes. You knew it was comin’, but you didn’t know when. We took incoming rounds from the opposing force’s mortars also. They weren’t a very good judge of distance. If one got close, you might get hit with shrapnel if you didn’t have cover. A couple of NVA ground troops tried to penetrate our positions, but they failed. We had troops around the perimeter.”

‘You see things…’

On another occasion, Eklund suffered an injury that was considered “non-combat.” While hiking a load of trash to a pit at LZ Betty, a fire exploded and blew him into the back of a vehicle. “It burned my back and one arm, so I was put on light duty for almost three weeks.”

Part of his light duty was, “to put it exactly—it was burning shit,” Eklund says. In the outhouses, 55-gallon barrels cut in half went under the toilets. “You had to pull those barrels out, and pour coal oil in them, and light ’em, and you had a long two-by-four”—he shakes his head and starts to laugh at the recollection—“and you’d find a place to sit in the shade, read a book, whatever, go over now and then and hit the can on each side, and stir it up, and put more fuel in it, and relight it, ’til there was nothing but ashes. It smelled just like you’d imagine.”

Remembering such “lighter” moments can be helpful, because Vietnam brought its share of heavier ones—moments Eklund says he has wrestled with in dreams over the years. “You see things, and you just kind of let ’em go. Talking about them doesn’t do much good,” he says. “You saw body bags. I was at one of the firebases in the Central Highlands, and we had two new guys come in, and they were directed to a bunker, and somehow a grenade was dropped, came off one of their packs, and it concussed. They brought ’em out right past me, the medic was with ’em, and he just shook his head. I guess the most regretful thing is that I didn’t even know their names.”

‘To me it was an honor…’

Eklund survived his tour, finishing out his service at Fort Hood near Killeen, Texas. He finally met his daughter in person. His post-military life unfolded first in East Tennessee, where he began a career in manufacturing of automotive seatbelt parts, and eventually in Oak Ridge, where he went to work for Boeing Aircraft in 1983. He retired in 2012 and has continued to make his home here, near two of his nine grandchildren.

It was only years after Vietnam that Eklund learned about the comprehensive benefits available through the Veterans Administration. After meeting a VA rep he went to high school with, “he set up my hearing appointment, my PTSD appointment—all I had to do was go,” he says, adding that he’s been going yearly ever since. “I would advise anyone who has never been to the VA for additional benefits to go. It’s the best thing I ever did.”

Reflecting on his military service, Eklund harkens back to his dad, Carl, who passed in 2011, the same year as Don’s mother. “To me it was an honor, because my father had done it also, and at least I could follow in his footsteps.”

The elder Eklund was a second lieutenant in an engineering corps during World War II. “He went into Italy to build bridges, and he got wounded—shrapnel in his hand,” the younger Eklund says. “I’m sure he was [proud of me]; we didn’t talk about it much. I never talked about it, and he didn’t either.”

In the case of both men, the silence was no reflection of the level of well-deserved mutual respect and admiration they shared for the service they had rendered to a grateful nation.

Comments are closed.