Centenarian WWII veteran Milton Jones energized Oak Ridge and Knoxville’s radio waves

When Milton Jones was a teen in the 1930s—no, that’s not a typo—he would catch a bus for the 12-mile daily ride from Bluegrass to Farragut High School, where he later graduated as part of the class of 1941. Enduring Depression-era challenges—“we didn’t have a car to get around in, except maybe an old [Ford] Model A,” Jones recalls—the future Oak Ridge Manhattan Project expert, World War II US Navy veteran, and longtime Knoxville radio engineer could scarcely have imagined the modern technology he would use in 2024.

“Milton is fiercely self-sufficient,” says family member Hanna Jones. “I mean, he moved an 85-inch TV in the box out of his car before church on Veterans Day. He can do anything with his hands. He’s utilitarian. He mows his lawn. He splits wood. And he emails. What 102-year-old emails?!”

For his part, Jones—born March 20, 1922—laments that while he navigates in today’s computer age fairly deftly, he’s struggling to keep up. “Most recently the technology has left me with problems,” he told Cityview. “It has advanced so far, I just can’t get around in the latest things, like these smartphones. I’ve got one but I can’t operate it.”

That might be the first time in his century-plus of life that Jones has conceded an inability to solve an electronics puzzle. Ever since his early days of experimenting with amateur radio equipment from his family home near what is now Northshore and Pellissippi (I-140), Jones has frequented the front lines of leading-edge audio communications.

Forged by the Sea

While he was drafted and served with distinction in the Navy during World War II from 1944 to 1945, stationed on the USS Indiana battleship on the West Coast, his fondest recollections of work center first on his role in the Secret City that later became Oak Ridge, and then on his 40-plus-year career in commercial radio.

In a departure from most of the veterans we have featured, Jones—while proud to have helped secure America’s freedoms and foster peace across the world—calls his tenure in the Navy at the height of the Second World War “not too eventful, believe it or not.”

After training at Naval Station Great Lakes north of Chicago, he was assigned to the Indiana out of the Seattle area, where he served as a fireman in the central control room. “But the ship had come in from an operation and they had to redo the whole main-drive section, so we sat there while they worked on the ship.”

He was later transferred to a base near San Francisco, where, again, the highlights were less military and more off-hours: “I wound up at Market Street downtown for a long time. We’d thumb [hitchhike] our way across the Golden Gate Bridge. One time I walked it. It rained just about all the time. I was only at sea for a short time.”

Even so, Jones’s service to his nation was far from limited to his Navy tenure. Before and then after his time in the service, he worked on the hush-hush Manhattan Project in that top-secret city northwest of Knoxville.

‘Not a Peep to Anyone’

After high school and completing two years of radio training at Madison College (now Madison Academy) in Nashville, earning his first-class FCC license, Jones taught radio theory in Lexington, Kentucky, to students whose skills were in high demand as the war effort ramped up.

Upon returning to Knoxville when the class ended, he received a letter from Clinton Engineering Works inviting him to interview in New York City. Curious, he went through the process and was told to “report the following Monday to the administration building, the only building on the turnpike” at a then-unnamed location 20 miles from Knoxville.

“About 25 others had received the same assignment as I had,” he recalls. “There we all sat in the class. An instructor told us, ‘Everything is secret here. It’s coded. You won’t say anything about anything, not a peep to anyone.’”

At this point in the conversation, it becomes easy to forget that Jones is 102. His vivid memories and encyclopedic knowledge from the Secret City cascade out like pulsing waves from a radio tower.

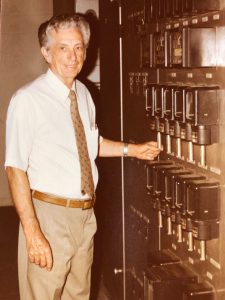

Jones applied his electronics background to the government’s efforts to develop nuclear fission in order to build atomic bombs. He worked as an electrical shift foreman, supervising a team of eight that maintained and serviced thirty-two calutron uranium enrichment units—components that were vital to the fission process.

After explaining more of the details, Jones pauses before proclaiming, “Oak Ridge is the greatest thing in my life. It was such a massive operation. The government threw everything we needed at it. I was reminded that ‘this stuff is going to the front lines to help our troops.’ The pressure was on night and day to get everything going.”

Four Decades of Airwaves

Following the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of the war, Jones helped to wrap up the Manhattan Project, after which he pursued a civilian career, ultimately gravitating to his first love, radio.

For the next four decades, he served as chief engineer for Dick Broadcasting, WKGN and WIVK. After retiring in the 1990s, he worked as a consultant in broadcast technology. His highlights of that momentous era include working on Knoxville legend Orton Caswell “Cas” Walker’s radio show, and with Big Jim Webb. “A young lady named Dolly Parton came in one time, with this little teen voice. She was a nice, wonderful girl.”

He also crisscrossed the Southeast to install transmitters and towers, establish new stations, and check on existing operations; traveled with Tennessee sports broadcasting hall of famer Lindsey Nelson; engineered UT games with John Ward; and interacted often with his favorite Vols football coach, Johnny Majors. One time, Jones relocated the UT radio station transmitter from a smokestack antenna at Ayres Hall to a new transmitter out west on Middlebrook Pike. It was eventually moved to Sharp’s Ridge, where it and many others stretch to the sky today.

‘I’m on the Lord’s Diet’

As one of Knoxville’s most seasoned lifelong residents, Jones holds an affinity for the smaller hamlet of his youth that he has watched grow into the bustling “it” city of his golden years.

“I look at Knoxville as the little town it used to be, mostly farmers, and the people cooperated and got along,” he recalls. “We lived in an old house, my grandmother’s house, and we didn’t even think about locking the doors at night. Nobody gave anyone trouble. A lot of people in Knoxville still feel that-a-way about it.”

In the 1950s, he met his future wife, Ruth, on a double date. The Joneses wed in 1954 and were married for 69 years. They had four children and eventually five grandchildren. Ruth passed away last October at the age of 92, “peacefully in her home, with her devoted husband by her side,” according to her obituary.

For all of those years, Jones has lived in the same house in Martha Washington Heights south of town. “It takes a lot of wood to keep it warm in the winter,” he quips.

When asked about the keys to his longevity, he says, “I’m on the Lord’s diet. I don’t eat the swine. The sea scavengers are lobster and shrimp, so we don’t eat those. I’m mostly a vegetarian.” He pauses. “I love turkey, though; I have to have my turkey.”

It might not hurt that his mother lived to 112. “She said her secret was drinking grape juice,” Jones says with a chuckle.

Despite only a short tenure in the US Navy, Jones has never lost his love of salt water. One of his favorite hobbies was deep-sea fishing. “I couldn’t wait to get down to Florida when I found out they were coming back with trailer loads of fish. I made a lot of trips to Destin and Fort Walton. It was my second home.”

Honor Where It’s Due

On Veterans Day 2023, Jones was recognized in a special service at his longtime place of worship, Knoxville First Seventh-day Adventist Church. As Hanna Jones recalls, his family, friends, and several civil officials were “privileged to recognize Milton for his service to our great nation during World War II, both in the Navy and on the Manhattan Project.”

Among the dignitaries were U.S. Congressman Tim Burchett and Knox County Mayor Glenn Jacobs, who joined Jones’s family, Pastor Matt Durante, and the entire church to honor their favorite centenarian.

“Congressman Burchett read the remarks he entered about Milton into the House of Representatives Congressional Record, and presented a copy of those remarks and a flag flown over the United States Capitol in his honor,” Hanna says. “Mayor Jacobs also read a brief biography of Milton and offered his sincere gratitude for his many contributions to Knox County and East Tennessee.”

Fittingly, several media outlets attended to capture the event and feature Jones on their broadcasts. Of the day and the spotlight shined upon him, Jones said, “It was unbelievable. I could never have thought I would be standing on a stage with our congressman and our big mayor.”

That was a reference to Mayor Jacobs’ six-foot-eight-inch height. For his part, the mayor turned to Jones and asked, “The other day you had your log splitter taken apart and were putting a new engine on it?” When Jones nodded, the mayor responded with a laugh, “I can’t do that now!”

And yes, this was the same morning when Jones unloaded that 85-inch TV before church (which made him right on time instead of early to the Saturday service). Is there anything he hasn’t done or couldn’t do? We wouldn’t bet the farm in Bluegrass on it.

Comments are closed.