The mountains teach us lessons in our most vulnerable of moments

Clouds littered the valley floor of Pichincha province as we nudged recalcitrant cattle and straddled fraying fence line. My team was getting their first taste of altitude on this perfect March morning as we approached the 11,000-foot mark here on Ecuador’s Pasochoa mountain. Heavy breathing meant more frequent stops and calorie breaks. “Drink up!” I preached as we melted into the swaying grass and entered a treeless plain.

It would be my third time on this dormant volcano in the shadow of mighty Cotopaxi. Our Knoxville group was stretching their legs and lungs, snapping photos, and awing at the valley of the volcanoes. My assistant guide, Renee, was setting pace for our rabbits who would run if we let them. When we paused at 12,000 feet, five new altitude records were set, and we took a minute to reflect and hydrate. Another hour was required for the rocky prominence and some class-3 scrambling would see us realizing our first summit of the expedition.

One of my team was struggling, and I soon realized that he would have to descend. This is quite typical and out of our eight-person group, expected. I elected to descend with my friend, unconcerned about missing the last 1,400 feet. We would have to make this up, but I had been in country and at altitude longer than my client and we had plenty of time. I recommended he begin Diamox, an altitude medication, along with other team members who were having mild symptoms such as headaches and sleep issues.

Two days would find us eying Rucu Pichincha. This beautiful mountain dominated the Quito skyline. Topping out at 15,600 feet it required a cable car ride from the valley floor to begin our climb. I stood in line for tickets as they leisurely opened the gate at 10:30 a.m. This meant our hike would be accelerated beyond my comfort, but these are South American curveballs I have learned to accept in my travels here over the past two decades. Renee was giving the ticket lady a Spanish earful.

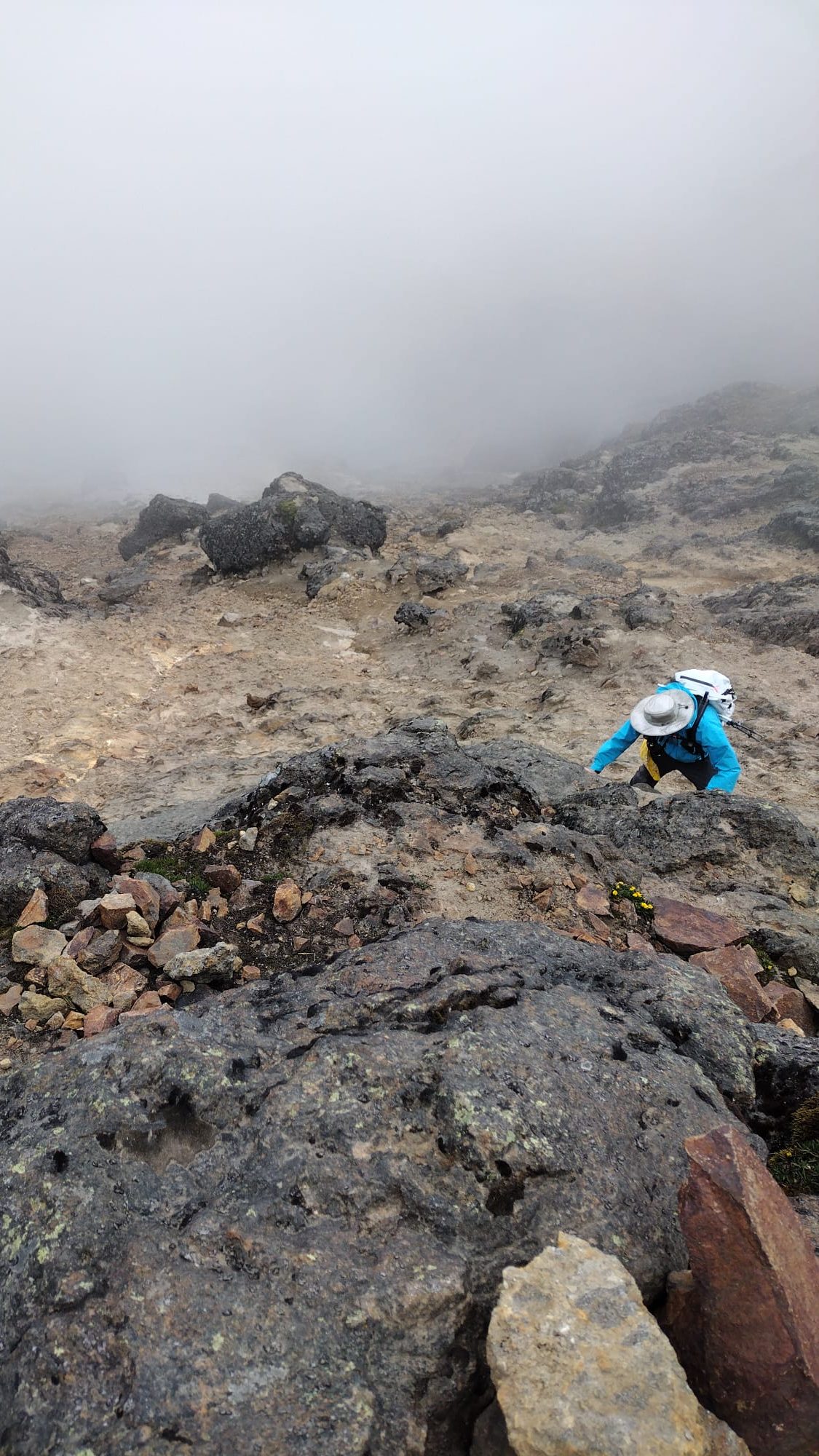

Rucu is postcard photography beautiful. Through a moving cloud forest, glimpses of the 30-mile “avenue of the volcanoes” whispered furtively as mountains such as Cayambe and Rumiñahui dangled a slipper in our direction. Just long enough to elude our best photographic efforts, it seemed to Martin Hunley. We threaded through the mist to a scree field, our last obstacle before climbing the final pitch to this 15,600-foot summit. The entire team would realize even newer altitude records and stood together high above Ecuador’s capital.

Nestled in the backdrop of Cotopaxi we looked like extras in a spaghetti western with our ponchos and helmets saddling up on horses for a “rest day”. We would soon find ourselves tackling part of the big peak over our shoulders the following morning. Cotopaxi means “neck of the moon”. On the right night, it can be seen perched perfectly cradled in the volcano crater. My two summits of this volcano would in no way compare to what was waiting for us on mighty Chimborazo. But we would crawl up part of it the next morning.

The weather came in with fury as we offloaded our four-wheel drive vehicles for the first leg up to the refugio. What began as rain at 14,000 feet turned to sleet that came in sideways and raked our exposed faces. We were soaked and the winds picked up, gusting to 50 mph. We took shelter at the Jose Rivas Refuge. A round of hot chocolate was just the ticket on this blustery mountain morning as I related tales of nights spent in this place with other groups. Our local guide was to escort us another 1500 feet on this hike, but the wind was not complying. It was strong enough to lift our legs. We made 16,200 feet our high point on this particular afternoon. Three thousand feet remained between us and that volcano top, but Cotopaxi was not our objective on this expedition. We needed that extra elevation, and I was coming to realize we were getting behind the eight ball.

All but two of my group were relative newbies to this mountaineering game. My trips are structured so that folks have multiple bail points, and some took advantage on that blustery morning. It was becoming apparent that most of my team would not be going for the summit of mighty Chimborazo a few days hence. This altitude and weather were a precursor to our summit day. As a precaution, I encouraged my team to avail themselves of Diamox to help with acclimatization. I could tell a difference when they had it in their system; tingling extremities and frequent urination are calling cards. I have seen it work wonders on other trips with clients who would otherwise have gone home. My team was feeling well after we descended and made the move over to Chimborazo base camp and sunshine.

One more hike and we would take off for advanced base camp. At 17,600 feet it matched the elevation of Everest base camp. We parked at Chimborazo National Park and shouldered some heavy packs. Two hours and 1500 feet, we shuffled into our group dome tent for a few hours of rest before a midnight start on Ecuador’s highest peak. Nothing seemed wrong, and I was feeling stronger than ever.

Three hours into my five hour “nap”, I awakened with labored breathing. Sitting upright, the mild tinges of a headache were coming on. Invoking the usual antidote, water, I tried to drift back off. By 11 p.m. we abandoned this futile rest effort and rolled out to sort gear for this, the longest of days.

Stars glistened initially as we moved upwards in one-to-one guided groups. I had the privilege of roping up with Christian, my partner from Cotopaxi two years prior. He had so many ascents of this peak he lost count. A sudden wave of nausea overcame me here as we climbed a vertical rock face on the via ferrata route. Snow began to spit in our faces, and the darkness of the Andes deepened with retreating stars. We had split from the others; Christian wanted to give me a more “exciting” climb than my clients. He knew I had a fair amount of altitude experience and would perhaps enjoy some technicality. I just wished for an easy ascent and struggled not to vomit, as he belayed me up vertical rock.

The rope tightened between us as Chimborazo steepened with soft snow and the occasional crevasse dividing glacier. We caught up with my friend, Richard Hatten, whose bobbing headlamp was signaling crampon difficulty. Soon I encountered Cris Emberton, another one of my clients who was moving steadily with her personal guide. We eased past and that is when my troubles really began. Uncontrollable dry heaving stopped me dead in my tracks here at 19,500 feet. Christian paused to witness this strange sight. As the wind continued whipping snow, conversation was futile. I convulsed about six times and leaned over my ice ax.

Nothing was on my stomach but that didn’t keep me from retching uncontrollably. I remember looking at Christian who spoke what was already on my lips. We had no choice. I was suffering from acute mountain sickness. These were classic symptoms. I thought about all the times I had to turn clients around on other expeditions. There was but one choice and he didn’t need to tell me anything else. We began our descent back to advanced base camp. I wished Cris luck as we retreated down the steep snow slopes.

I couldn’t help but think about Sir Edmund Hillary, history’s most famous climber. After summiting Everest, he went on to climb various peaks but started experiencing altitude sickness and had to be evacuated from a few mountains. Advancing age had taken its toll on this New Zealander and caused him to accept that his days of big mountains were over. I tend to think his weight and abandonment of fitness came into play. For me it was a combination of factors. One is not having gained the early altitude with the rest of my group and the other was the big jump from 16,200 feet to 19,500 feet. Had I been taking Diamox, this would not likely have happened. Drugs allow you to pull this off sometimes. After all, bottled oxygen is cheating, and I have had no problem using that in the past in the Himalaya.

Three of our team managed to gain the fore summit of Chimborazo: Richard Hatten, Emily Brewer, and Dan Lewis battled through the wind and gale to reach 20,400 feet. Their accomplishment snuffed my humbling effort and with great pride we welcomed them back into advanced base camp. Emily proclaimed, “This was the hardest thing I have ever done. I don’t know how you do this all the time.” Well, Emily, apparently it isn’t all the time. But for you, there will be plenty more. The mountains and our bodies make these calls. I have learned to heed them both.

Comments are closed.