Charlie Orr built roads and survived harrowing moments in Vietnam

Of all the vivid memories Charlie Orr holds from his tour of duty in Vietnam from late 1966 to early 1968—and there are many; a few will be told here, others are too gruesome to recount; take it from one whose face turned greenish-pale at the hearing of them—perhaps the one that best encapsulates his war experience lasted less than five seconds.

As Orr tells it, “I was wounded one night chasing the Viet Cong through the jungle, when shrapnel caught me in both legs, between my knees and ankles. Boy, it hurt like hell. I had to walk back and be treated. On the way I passed through a dry creek bed, and about 15 yards to my left, I saw a [Viet Cong soldier] trying to get back to his outfit. He stepped into the open to cross that creek bed at the same time I did. We looked at each other, and I nodded my head, and he nodded his head. Then he went his way, and I went my way. He was just a kid. I could tell he didn’t want to be there either.”

A few seconds. No words. No weapons. Only a look in each other’s eyes, an acknowledgment, and off to mend—if mending were possible—before the next battle.

Secrets and the City

Some 26 years before that frozen-in-time moment in Southeast Asia, Charles Eugene Orr Jr. had been born in Bristol, Virginia, on October 8, 1941, two months before Pearl Harbor changed the course of the American twentieth century, ushering in both the Second World War and the nuclear age.

In 1943, the family moved to Oak Ridge after Orr’s father, Charles Sr., was assigned by the US Army to operate heavy equipment for a contractor that was working on a classified construction project.

While the Secret City grew to a beehive of activity during World War II, with up to 75,000 residents, Orr recalls his childhood as spartan: The family of four, including a brother four years Charlie’s senior, lived in a “tiny trailer” with no electricity, no running water, and a shared bathhouse (one side for men, one for women). Armed men on horses patrolled the perimeter of the city. No one knew about the Manhattan Project under development.

In 1954, when Orr was 13, the City of Oak Ridge was formed, and the trailer homes were shuttered. Orr’s father bought 56 of the trailers and moved the family to Solway, about 10 miles to the southeast, establishing a community on 16 acres he had purchased.

Among the highlights of those years was a swimming pool that Orr Sr. dug—and we’re not talking some cute little backyard baby pool.

“He built that pool with a big diesel dozer—40 feet long, 85 feet long, and 13 feet deep,” Orr recalls. “It was the talk of Solway, and people would want to come swim. Mama was smart, and she charged folks, 50 cents for adults, 25 cents for kids. She was the brains and Daddy was the brawn.” (The elder Orr was 6’3”, 250 pounds, “all muscle,” his son says.)

After graduating from Karns High School in 1959, Orr attended UT-Knoxville and then ETSU while working summers for Ralph Rogers at the rock quarry where his dad served as a foreman. There, he learned to operate a road grader and other heavy equipment—skills that would soon serve him well halfway around the world.

In Search of Charlie

Fast-forward to December 1966. Orr had followed a serpentine path since enlisting in the US Army in the Army Security Agency (ASA) signals intelligence branch. He’d completed basic training at Fort Jackson, SC, and advanced infantry training at Fort Gordon, GA; trained in morse code at Fort Evans, MA; received orders to shift from ASA to combat infantry (as US involvement in Vietnam was ramping up); trained in Germany through “the durn middle of winter” as a combat engineer; been assigned to Fort Campbell, KY, for six months of jungle-warfare training; and now, he was in Seattle, WA, boarding “an old cargo ship that had been converted into a troop carrier” for a cramped 21-day journey.

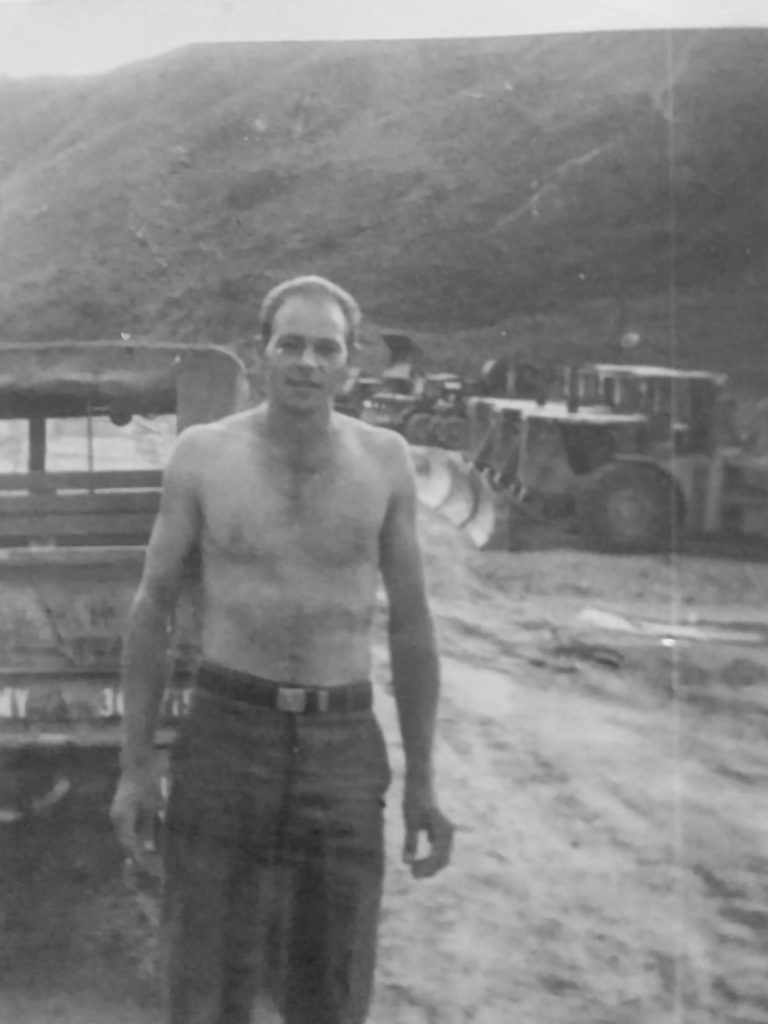

Having raised his hand when asked who could drive a road grader, Orr would be tasked with moving dirt and rocks and building roadways in Vietnam. He arrived with his fellow soldiers in Vietnam’s Quin Yan Harbor, some 200 miles up the South China Sea coast from Cam Rahn Bay, in full combat gear, “loaded for bear.”

His grader had been shipped and was waiting for him. Orr was first assigned to build an ammo dump, creating tall berms to protect the munitions.

A few days after arriving, Orr was on his grader watching a fellow soldier, a “kid around 19,” walk up a mound. “I saw a flash, and from an angle, a sniper shot him right through the shoulder just above the heart,” Orr recalls. “I jumped off the grader, tried to stop the bleeding, holding my hand over him, but he was hit bad. Some other people and a medic came over. That’s when I knew then we were in a pretty hostile area.”

No one else had seen the sniper’s trajectory. When a helicopter arrived to evacuate the wounded man, Orr said, “Do not go over that ridge right there.”

“Why not?” the pilot, a lieutenant, asked.

“I saw the flash from the rifle from that way,” Orr replied. The pilot laughed. “He didn’t believe me, I guess, and he thought I was being disrespectful.”

The pilot, a co-pilot, two medics, a side gunner, and the injured soldier “lifted off and headed right over that ridge, and the sniper shot at the rear rotors. I was watching when it crashed over the ridge. I thought, Good Lord, if they had just listened to me . . .”

Orr pauses. “It’s just like I’m doing it all over again right now,” he says with a heavy sigh.

He volunteered to ride over toward the crash site. It wasn’t a pretty sight. The crew and passenger of the chopper had all been incinerated.

“We reported them all dead and I went back to building the ammo dump,” Orr says, adding, “I had seen death before, but not like this. I thought, Boy, this is terrible, and it made me be more careful.”

Later, Orr moved inland to a “mini base” in the foothills of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. He was part of a crew building a north–south supply route, code-named QL1, which later became—and remains—National Route 1.

He often saw combat, building roads by day and going on patrol to assist other combat divisions when called upon. “My grader had lots of little pings in it from being shot at.”

Fellow soldiers “were chasing Viet Cong through the jungle, got lost, we were called us in to help find them. We’d go into little villages, talk to the ‘mama sans.’ They had little bamboo fences set up. We saw pandas, some great big old cobras, rice paddies, little farming areas.”

Orr tried to build figurative bridges as well. “I would stop my grader, hold my hand in a peace sign, put my weapon down. I didn’t want them to be afraid of me. Kids would come back and stop me, and sometimes I would give them a little bit of candy or something.

“I was always looking for VC” as they recruited young men and women from the villages, Orr recalls. In some cases, the enemy soldiers developed a soft spot for this American Charlie. “Once the VC saw that I was helping these villages, cutting drainage ditches while building that supply route, they liked that; these were their mamas’ and daddies’ villages. I think they looked out for me. I could have been killed several times, but they knew who I was and were less apt to shoot at me.”

Saving Children from a Fire

Once, when Orr was building a helicopter pad in the jungle, he noticed a fire burning down the hill and across a creek. It was an orphanage. “I saw little kids and nuns running to the creek to get water.” He drove his grader as close as he could to a small bridge, shut it off, took a bucket, and ran to assist. He helped put out the fire and rescued some children from the building. The appreciative nuns wiped his singed, sooty face and brought him a cool drink.

“They were so grateful, and those kids . . .” Orr pauses as the emotion rises.

“I got back on my grader, and there was a jeep sitting there with a colonel. He said, ‘Orr, I’m gonna see you get a medal for what you just did.’ I said, ‘Sir, I don’t know about that.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna see [General William] Westmoreland this afternoon,’ and he wrote down my name and company.”

The good feelings would fade fast, though. “When I got back to base, there sat my company commander and my first sergeant. The CC said, ‘Orr, you are under house arrest and I’m gonna court-martial you. You abandoned your worksite.’” For weeks, Orr was forced to fill sandbags with a shovel. Others spoke up on his behalf—“He put that fire out and saved lives!”—and the house arrest ultimately ended. The medal was sent down, but the CC would not give it to Orr. He wrote home. “My mama went to see Congressman [John] Duncan, and he wrote to Westmoreland; he promised to give me that medal, but I never got it.” The court-martial was rescinded, but Orr was fined $50 for “inappropriately taking government equipment off-site.”

Gruesome Discoveries

Here is where some of Orr’s memories turn even darker. “One time in the jungle, we walked up on a little clearing and there was a soldier’s body lying there . . .” Readers will be spared more details; suffice to say that “my mind just snapped then,” Orr recalls.

On another day, a soldier had been tortured and was still alive when Orr and his platoon came upon him. As the soldiers were directed to keep moving, “somebody put him out of his misery; probably our platoon leader. We heard a shot after we left.”

Yet another day, while returning from a day of grading, Orr “saw three VC up ahead run across the road with a recoilless rifle and a tripod. They set it up on the edge of the jungle. I had the grader wide open, started firing my M-16 with one hand like John Wayne, shooting over their heads. I made it down the road. A dump truck was headed the other way, with an officer and a driver and three guys in the bed. I stopped and told them, ‘Turn around! There’s a rifle hidden a half mile down the road.’ They said, ‘Nah, we ain’t goin’ back, we’re carrying mail.’ The officer said, ‘Soldier, move on!’

“The next morning as I came back I found that dump truck, burnt, all five of them killed. Some of those officers just would not listen to you.”

Orr sighs. “I could tell you other stories,” he says—but not all of them are the sad kind.

“There were some good moments, like with those little kids on the side of the road, giving them a bar of soap or candy—I wasn’t supposed to be doing that.

“This little girl came up one time and said, ‘VC want to talk to you.’ I said, ‘What?! No.’ She said yes, at the edge of the jungle. ‘No hurt; you number one GI.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ I walked over about 20 or 30 yards and these two VC stepped out. I didn’t have weapons. We held our hands up and tried to talk with signs. They said, ‘That my sister, you been good to my sister. We glad.’ That sort of thing probably kept me alive.”

Orr “blocked out” the possibility of dying in combat. “I always figured I would make it. My thoughts were mostly right at that moment. When I was running the grader, I had to concentrate; this was a massive piece of machinery. I’m not one to dwell on things anyway.”

Back home in East Tennessee, Orr would end up working for the phone company in Oak Ridge for 26 years, where his wife, Doris also worked for 32 years. The couple had met shortly after Charlie’s return from Vietnam in early 1968, at the Amvets center; she remembered Charlie from swimming at the Orrs’ pool in Solway, where he had worked as a teen lifeguard. Their whirlwind romance led to the altar on February 12, 1968.

The Orrs reared two children: daughter Scottie, born in December of 1968; and son Jay, born in 1970. Charlie and Doris make their home on 10 acres in Solway along Beaver Creek, a tributary of the Clinch River. Among other pursuits, Charlie is a musician who is part of a band called The Golden Eagles, where his friends include 100-year-old Ruth Skidmore, the subject of a feature article in the July-August 2023 issue of Cityview.

Thinking about his military service and his tour in Vietnam, Orr says, “I felt like I couldn’t do anything better than to help those people stay free of communism. If we don’t try to stop it over there, it’s gonna come to us. I was as proud as I could be to wear that uniform.”

Comments are closed.