Stories of the riches found in the ocean deep and on the side of East Tennessee cliffs

Del Scruggs was in his twenties when he caught wind of what was going on in Florida. Whispers of buried treasure wafted up the hollers of East Tennessee in 1985 and Del was keen to get in on the action. He somehow managed to convince his cousin to mount up on bicycles and head for the Keys. “We tore up a lot of salad bars on the way down,” Del laughed. It took them almost two weeks before he finally caught up with Mel Fisher, having parted with his relative in Gainesville. Fisher was gaining notoriety among the scuba community for hooking the biggest prize. If this treasure hunter was initially reluctant to take on a landlocked diver, when he learned how he got down there Del was hired on the spot.

I attracted a small crowd when my climbing buddies learned Del was going to “dig out” some of the booty he kept from his diving days. Milling about his establishment, appropriately named The Lilly Pad Hopyard Brewery, due to its proximity to the Lilly Bluffs area, patrons begin to file in on a Saturday afternoon and line up for his beer offerings. Some are chalk-covered dirtbags like me, but most are a mix of locals, tourists, and motorcyclists. A band cranks up in the background as Del educates us on the difference between a doubloon and piece of eight. I finger a brittle-looking golden oval he has mounted on a necklace. The sand has scrubbed many of the markings but it’s clearly a coin. To think this currency was struck in the early 1600s somewhere in Bolivia and laid on the bottom of the sea until Del freed it boggles my mind.

Twenty-eight ships comprised the fleet that included Nuestra Senora De Atocha when they departed from Spain in 1622. Spanning 110 feet, this galleon took two months to load and document all the bounty from Colombian mines. It was said some of the most beautiful gems of South America were packed away in the recesses of this titanic vessel. One particular stone, dubbed the “Atocha Emerald,” is estimated to be worth upwards of $4 million. Forty tons of silver and gold, much in the form of ingots, were recovered in what has been described as the most successful treasure hunt in history.

For that reason, the Spanish dispatched a full complement of 82 infantrymen to guard this wealth, which brought the ship’s manifest to 265. Their initial plan to avoid the well-known Caribbean hurricane season was pushed forward as a result of clerical issues in port. (It takes a few minutes to record tons of treasure, apparently.) The fleet departed Havana and planned to skirt the Keys when they ran headlong into the very thing they were trying to avoid. Five vessels succumbed to this storm, described as producing mountainous waves. The following morning a passing vessel found five survivors clinging to debris. The remainder were trapped below decks and became part of the sea.

Fisher had been on the trail of the “Atocha Motherlode” since the ‘70s. It was an expensive venture for him, having lost his oldest son, daughter-in-law, and diver Rick Gage, when their bilge pump failed while scouting the shipwreck in 1975.

Del would spend two years making up to three dives per day. Del shared a story of one particular dive when he was vacuuming the seafloor and was struck on the side of his head by an object he had dislodged from its sandy tomb. (It turned out to be a gold bar.) To pass time, he juggled onboard the dive boat and recalls running afoul of the captain when it became apparent Del was tossing a couple hundred thousand dollars’ worth of gemstones into the air.

Del’s success brought a unique and enviable set of problems with the IRS. “He paid us in treasure. I tried to give them some of the loot, but they wanted cash!” After two years, Del cashed out with Fisher and roamed around South Florida, not having to worry much about returning to college for a little while. He did eventually make his way back to East Tennessee, complete his degree and marry Marte, “the greatest treasure of all,” he quipped. Ever the entrepreneur, he hung out a shingle in the Old City where patrons could pick up their own Atocha bounty. Del named his store Shipwrecked.

Del may have been looking for the next buried treasure when he purchased 20 acres right up against the Obed Wild and Scenic River area. Insular and wary of outsiders, Del made friends with the Howard family. Perhaps sensing his authentic Knoxville lineage (most of these folks were descendants of patriots who ended up with their bounty in the form of Revolutionary War land grants), he apparently garnered enough local credibility to obtain another 25 acres. He put a trailer up there and set about raising his family.

In the ‘90s, rock climbing was still fairly outlaw at the Obed. Self-proclaimed dirtbags like Kelly Brown were exploring these river bluffs and finding sandstone gold of their own in the hills. There were different factions competing for development of multiple areas in this nascent addition to the national park system. The Wild and Scenic River designation had been conveyed by Congress only in 1976. It is said that the name Obed stems from an early long hunter who traversed the area in the 1700s.

Four tributaries comprise this 5000-acre gem. These include the Obed River, Emory River, Clear Creek, and Daddy’s Creek. Some of the bluffs are 500 feet tall and include portions of the newly completed Cumberland Trail. Del was again uniquely positioned to capitalize on treasure. Kelly Brown describes the ‘90s as “the golden years of the Obed climbing scene.” Climbers turned the Lilly boulder fields into a local base camp until the NPS outlawed it. Del opened his wooded acreage to temporarily host these displaced rock jocks.

While Brown and others like Tony Robinson scouted new routes in minimally explored gorges, weekends were spent beneath the stars on Del’s property. It didn’t take long before he had established a dirtbag base camp on his land near the entrance to South Clear and Lilly Bluff. He was within walking distance to all the action.

I suppose Del was tiring of campers watering his pine trees, so he proposed having this gang chip in for a port-a-potty. “That’s where the idea of charging people to camp came up.” First, he put up a self-pay kiosk. I have personally spent many a night down in the woods above the creek, lulled to sleep by the sounds of owls and partying dirt baggers. Del says that the honor system wasn’t necessarily being honored (I put in my $5 every time, Del, Scouts honor). It was only natural that he and his Lilly Pad would host the annual Obed Trail Day event. Climbers give back in the form of trail maintenance and service the 300 climbing routes. Del’s Lily Pad serves as base of operations for this cooperative between the East Tennessee Climbers Coalition and the National Park Service.

Frank and Ann Harvey serve up heaping portions of gumbo at Del and Marte’s following an afternoon of sweat equity that often sees up to 100 volunteers. We come to give back. Many are the afternoons that weary and mud-covered mattock toters have returned from an area called Y-12 or Stephen King’s Library, moving stones and rerouting or re-bolting. Timmy Campbell laments the E.R. bill after being “kissed” by a copperhead while sweating away one September morning on an overgrown trail near South Clear. Everyone has their own tale of being lit up by yellow jackets which makes dipping in the river all the more necessary. Dirt and chalk join cares which are washed away to float down the gorge at infamous “Diaper Rock.”

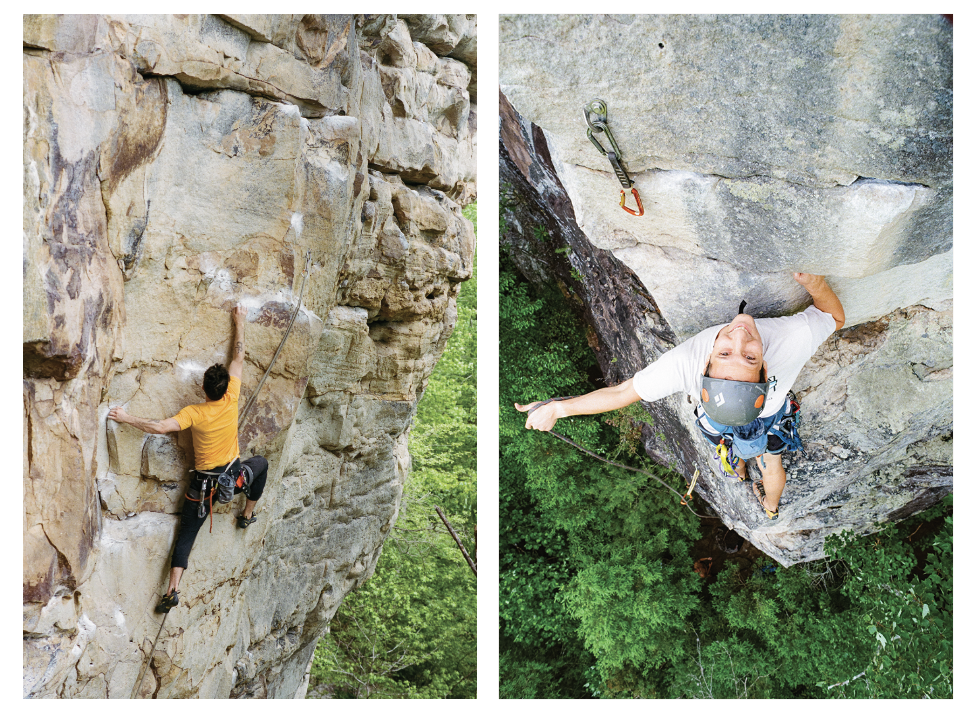

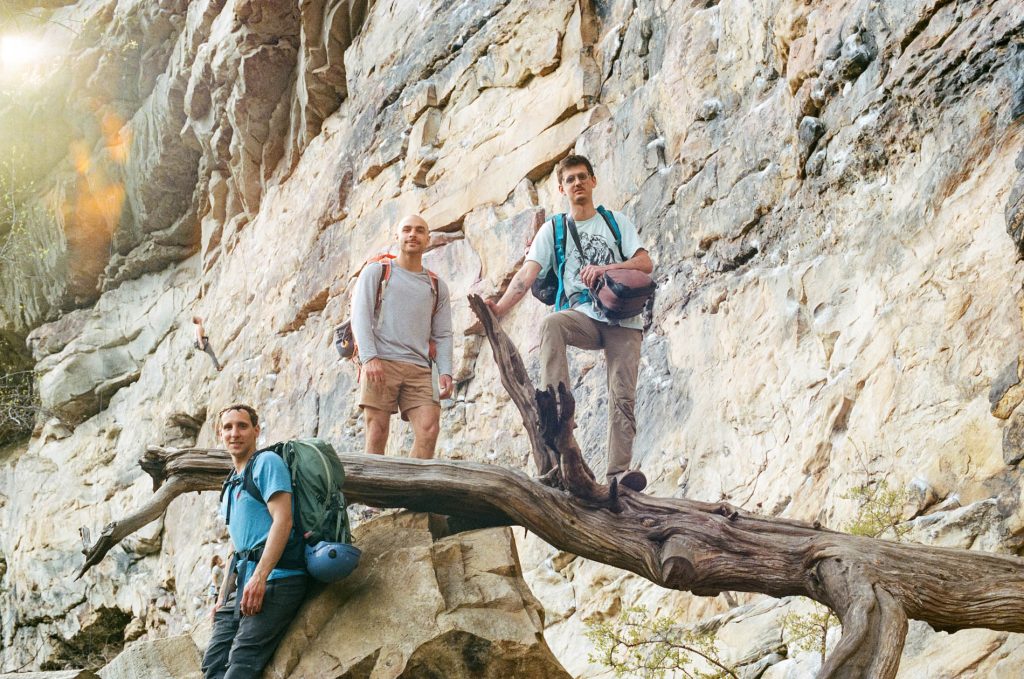

Kevin De Angeli had already led up a route named “Lilian’s Arete.” Hiking from the Lilly Pad, it is about one mile through the woods and a few hundred feet down the bluff. (It made no sense to waste a trip to Morgan County on the day we photographed Del and Marte without some hang time.) Hailing from Argentina, Di Angeli finished his PhD at UT and remained, in part, because of the climbing. Dangling from the very top of this beautiful, classic North Clear climb, is Patrick Caveney, another PhD from the Tri Cities. He is trying to photograph me as I pick my way around the crux move. Distracted by the breathtaking river gorge below, Caveney reminds me he is balancing with expensive camera gear, so I get back on belay and continue delicately, tiptoeing my way skyward.

We finish taking turns on this route in an area named the Squeeze Ledge. Getting here literally involves punishing torsion through a rock tunnel not recommended for the claustrophobic. Alex Lewis, another overeducated doctor, has laid out a full rack of trad gear. While we were swinging around the arete, he was eyeballing a route inauspiciously dubbed “The Crack.” Deftly placing cams, hexes, nuts, and other technical gear into a varying width slit, he makes short work of this 50-foot sandstone puzzle. Traditional climbing areas are scarce in East Tennessee. Always humbled by these young men and their dexterity on the rock, I wonder if going back to the university would improve my climbing abilities. They definitely “school” me every time we harness up.

Rock climbing isn’t the only activity in the Obed, just my personal favorite. Hiking, paddling, and star gazing are but a few others. The Obed has received a distinguished international dark sky place designation due to the absence of ambient light. But if you mention the name in outdoor circles, climbing is probably going to be the first acknowledged sport. Once, while on an expedition in South America, a local guide surprised me with a question about the grippy Obed action.

In what turned out to be his swan song, author Cormac McCarthy takes us on a ride deep in Morgan County, through the town of Wartburg where the Obed Visitor Center may be found, over the hill down into this river gorge. Evocative and visceral, McCarthy “comes home” to a place still teeming and verdant in his final work, The Passenger. “I counted 273 creatures with their Latin names,” his main character, Western, notes.

Nowadays, Del’s primary focus is on his brewery. From the cold water of Clear Creek he divines competitive offerings that are in growing demand at establishments in Knoxville. If you spend any time with Del, you realize he is one of those guys favored by the same winds of fortune that blew him down to the Keys. Much like the estate of Mel Fisher where treasure is still being salvaged, Del continues to raise bounty from the depths of wild places. At the Obed, plenty of wild is what keeps folks like me and Del on that same road as McCarthy’s protagonist, west of Knoxville and worth the drive.

Comments are closed.