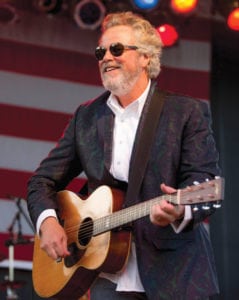

Robert Earl Keen will be coming to town with his “Merry Christmas from the Family” tour on December 8th at the Tennessee Theatre. Keen, or REK as he’s known, talked to us in late August about the song, the tour, and a smattering of other topics.

Keith Norris: I’m glad you’re’ coming back to town. You’ve been here more than a few times.

REK: Well I love Knoxville.

KN: What do you like about Knoxville?

REK: I love that square—what’s it called, Sundown Square?

KN: Market Square, but AC Entertainment used to do a show called Sundown in the City there.

REK: I also collect Cormac McCarthy, so I enjoy that about Knoxville. Some of the first shows outside of the state of Texas I played over there at the Down Home in Johnson City, so I really just love Eastern Tennessee altogether. It’s an incredibly beautiful part of the country, if not the most beautiful part of the state of Tennessee.

KN: This is your “Merry Christmas from the Family Tour.” Where did that song come from?

REK: Well, I grew up in Houston, and as you can imagine, there’s really not anything Christmassy about it—except maybe for green lawns and red necks, you know, so…

KN: We don’t have any of that around here, swear.

REK: Yeah, right. And so, our Christmases were not what you would have imagined if you watched any Bing Crosby kind of Christmas movie. At one point, when I was working on another record, I was kind of frustrated and it was about Christmastime. I thought well, I can get this knocked out, and I just started making up a song based upon my own experience, and was truly in the world of simply wanting to amuse myself. I was trying to get out what my Christmases were like, which were not bad; they were just not anything like what one visualizes when they start talking about Christmas.

KN: So Bob Hope was not involved.

REK: Not at all. After I wrote it, I played it for myself and a couple of my friends, and everybody kinda cackled, and then I played it for a guy who was producing the current record, and he just flipped. I realized at that point that there’s something here. The first time I ever played it to an audience that I recall was when I came back home to Texas before I made Gringo Honeymoon, and I played at this little honkey-tonk. It was near the holiday season, and it was the closest I ever remember to thinking I had a hit. When you do this music from the beginning, you keep thinking, “oh, where’s my hit, when is all the light gonna shine on me?” And that never really happened for me. When I wrote “Merry Christmas from the Family,” I thought “this is my hit. I don’t know where it’s gonna take me, but it is definitely my hit.” It always gets the same reaction. If I play it for people who haven’t heard it before, they’ll just freak out, you know?

KN: That’s the way it works for us, too. When a friend of mine bought the Gringo Honeymoon album, I got a phone call not too long after saying, “you’ve gotta listen to this,” and he played it over the phone. Tell me, why do you think that song works so well? Is it because of the characters—that we all know similar types?

REK: I believe so, yeah. We’re all imperfect human beings on this planet trying to create this almost Hollywood version of perfection that we all have in our heads. I’ve seen most people sort of strive to have that kind of storybook lifestyle, and yet we realize that we don’t. In some ways, if you have a sense of humor, you think it’s funny; if you’re a more depressed and pathos-oriented person, you might get real down and out about it. I think most people have a sense of humor, and they see themselves in that song.

KN: You said earlier that one of the reasons you wrote the song is that you were “amusing yourself.” How much of your songwriting relies on that?

REK: I’m embarrassed to say “more than you’d really want to know.”

KN: Actually, that doesn’t surprise me that much.

REK: This is a parody song, and I don’t do many parody songs, but occasionally I do one just for a hoot. Like Bill Hicks used to say, “It’s a Hoot!” We have a bus, and every year it goes in to get repaired or get shined up, and it’s owned by the Florida Coach Company. Anyway, when we go off tour, it leaves Texas and goes to Florida; they take care of it, fix it up, shine it up, do a few repairs—and then they send it back. Well this year, they didn’t have very many repairs, so they sent it out with Gordon Lightfoot. Gordon Lightfoot had it out there—I didn’t even know he was still alive, but he is—and they sent him out there in the bus. Our fiddle player Brian, who’s been with me a couple of years or so, started making this joke about any time anything didn’t work—say a handle broke off in his hand, or something wasn’t clean. “Damn, that Gordon Lightfoot,” he’d say. So then it became this big joke; everything that went wrong was Gordon Lightfoot’s fault. So, you know, once again for the heck of it, I wrote this song called “The Wreck of Our Prevost in Peril” to “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” you know? I mean, what good does that song do me? Nothing. Zero. But it was really fine, and it got a lot of laughs when I played it for the band, and it was really fun.

KN: Did that lead to a lot of Gordon Lightfoot covers?

REK: No. As a matter of fact, one of the lyrics was,

For years in our ears, we could not help but hear

Your sing-songy dramatizations.

KN: That’s great. Do you feel grateful for the list of people you’ve worked with. It’s pretty impressive.

REK: I’ve been really lucky. I’ve bounced around; I always feel like I end up with people who are like-minded in some way. I mean, maybe we’re not alike, but you know, we all love music. And we’re all really passionate about it. And I’ve been really lucky to be able to be part of any of this community.

On the other side of the coin, a lot of times I complain about writers and musicians who don’t talk enough about what they do and how they do it. I mean there’s that pontificating that people will do at some seminars and stuff—it’s just a bunch of bloviated crap. But you know, the fact is I don’t think we ever get down to really talking about the craft and how things are put together and how beautiful some things are and how complicated some things are. I thrive on that kinda discussion, and I’m sorry to say that I’m not one who usually initiates it. But I certainly am all-in once it gets initiated.

KN: Do you thrive on collaboration when you work with someone else on a song?

REK: I like to collaborate. I’ll tell you, because I’ve written so many songs by myself, people assume that I don’t collaborate, but I do. As I’ve gone on, I’ve done all kinds of collaborations, and I really enjoy it. A couple of years ago, I started going back up to Nashville and hanging out and writing with some people because I felt like I was kinda out of the loop—you know, I’m older, but I want to be part of it. I’m all about being in the fray. So I went there, and I wrote a lot of really good songs with a lot of really cool people. And some of the songs were really good, but they all just sort of went nowhere. A few of them got demoed; I finished almost every song I wrote with anybody out there. But—this is the good part—a couple of years ago, I wrote with these two young guys—one of their names is Cary Barlowe, and the other is Corey something—so they were Corey and Cary. How can you ever remember their names? Did you ever see that movie The Big Short? The two young guys that are from Boulder—those are these guys, I’m telling you. It’s exactly like those guys. These super high-fiving, really smart guys.

We sat down and wrote this song, and everybody was high-fiving and saying “this is a great song,” and nothing ever happened. I thought it was straightforward, cool—I was proud of it. But it was right down the middle of the plate—a pitchable, mainstream, bro-country kinda song. And nothing happened. And then, like a week ago, I get this email and it says these guys’ names, whom I didn’t remember or recognize, and it has my name attached to it, and it says the title of the song, which I didn’t remember. And I went, “what is this? Somebody made a real mistake.” But I knew the person who sent it to me, so I called her, and I said “what’s going on?” and she says, “yeah, you wrote that song with these two guys.” And I said, “I’m not being able to access that file here, Sarah.”

I played it, and as soon as I played the first two lines, I went, “Oh, I wrote those. Oh, cool, cool.” It was so exciting. And then, the fact was that the song itself was badass. It was really exciting. I was so happy to be a part of that and be in the whole world of it. It’s a different world now. In some ways it’s smaller, and in some ways it’s a lot looser. You know, it’s weird. People can get ahold of you easier, but a lot of times you don’t have this “hey, let’s get it done” thing, so you just let it go. Anyway, that one worked out. We’ll see. Somebody might record it. That’d be really good, because I’ve never really had a recording on the radio. Regardless, it was exciting to hear a good song by guys who knew how to demo a modern country song, which I can’t do. That kinda stuff is what they used to call mailbox money.

KN: I’d never heard that phrase before, but it makes sense.

REK: Right? All songwriters are always looking for mailbox money.

KN: I was watching an interview with Waddy Wachtel and Leland Sklar not too long ago where they were bemoaning how the industry had changed, that making music in the basement with a computer has changed the industry in negative ways. Do you agree?

REK: I can certainly understand their point. But I want to say this: look at it from an historical perspective. If you start from the beginning of recorded sound to today, at least every ten years there’s this change; every 30 years there’s a tsunami of a change; and sometimes, like what happened in 2005, there’s a double-tsunami. It just happens. In 2005, the internet came on full-blast finally, and CD’s went out the door. There’s no more CD’s. There’s no bricks-and-mortar any more in the music business. It’s all gone. And there’s all these arguments about micro-pennies and how people aren’t getting paid. And this is all true; this is all true. But you know what? It’s a brave new world. Change happens. You have got to do something new. As they say in the airline industry, “Shift happens.”

KN: You grew up in Houston where the floods recently happened. Do you have any commentary on that?

REK: The most exciting moment in my life was when I was five years old. Hurricane Karla hit Houston—category five or some crazy number like that. It was a big one. It was so exciting. I sat there with my little sister and my parents, and we sat underneath our big picture window that was taped up with masking tape: big X’s all over it. As we watched the house of our neighbors across the street, their huge hundred-year-old elm tree that you couldn’t put your arms around got blown over, and we just cackled, like “Ha, ha, the Jones’s lost their tree.” We literally lived across the street from somebody named Jones. The elm tree went over, just came out roots and all. Splat. And our street was flooded all the way up to our front door—didn’t get into our house. Our lights were off for three days, and you couldn’t have thought of anything more exciting.

KN: What should we listen to that we’re not listening to?

REK: Well, I think everybody should dig up their Greg Brown stuff. Greg doesn’t tour very much; he’s kinda burned out, I think. He’s brilliant. But not brilliant in a singular way: he’s got great romance, great sexuality in his stuff, and beautiful, beautiful description. I mean, the guy is truly a poet of untold talent. When I used to say “Greg Brown,” about one in twenty would say, “Oh yeah, I love Greg Brown.” But now I never see that. That’s a talent we should be digging back up. When they throw this word “Americana” around, I think they’re doing an incredible disservice not to be including somebody like Greg Brown. He seems to me like the voice of America.

KN: He’s got one of my favorite live albums, The Live One. Right up there with Guy Clark’s Keepers and your Live Dinner. How was it getting together for a reunion of that album 20 years later?

REK: It was a blast. I was just gonna do the show. And as we got closer and closer to the date, I thought I should invite some friends, and then, amazing to me, all my friends showed up. And we all sang, and we had the best time. I couldn’t believe it. At that particular show, I thought man, the next time I feel like that dude who was bemoaning his state in the music business—next time that even crosses my mind, I’m gonna stop. I’m not gonna do it; I’m not gonna say it; I’m not gonna follow that thought. To be able to do this, to be able to have all my friends and real cool, super-talented, great songwriters who are way better than I am, all being up there on stage singing a song…. Shoot, man. People would give their left arm to do that stuff, and I get to do it a lot.

Comments are closed.