Norris Hill’s battle for peace began

with an encounter in Iraq

It is early 1991, the height of the 42-day Persian Gulf War, in the Iraqi desert on the road to Baghdad. Some of the first U.S. Marine Corps infantrymen to enter through Kuwait in a caravan of Humvees are watching clusters of frail, threadbare Iraqi fighters—most likely teens but looking much older—emerge from makeshift bunkers and step forward in surrender. Among them is a thin young man clutching a wrinkled note. With fear in his eyes, he hands it nervously to a translator while speaking quickly in Arabic.

One of the Marines, 20-year-old sharpshooter Norris Hill from East Tennessee, shifts the rifle in his arms and nods toward the soldier. “What’s he saying?”

“He wants you to give this letter to his father,” the translator repeats, “because he thinks you are capturing him to take him out and kill him.”

“That’s not…”

Hill pauses. What he starts to say—what he is trained to say—is, “That’s not why we’re here. Tell him we’re going to take him and his friends to get medical attention, shelter, food, water. His life is about to get infinitely better.”

But looking into this young man’s eyes, Hill senses something deeper welling up within himself. He is struck by a sudden vision: What if I was this frightened boy? What if I had to say goodbye to my own father? What would I write in that letter?

As an unexpected torrent of emotion rises, Hill feels himself shedding a thick layer of ooh-rah machismo, letting it fall into the dust at his feet. This encounter will become seminal in his life, a marked memory, a key strand in a tangled nexus of war-fueled struggle, stress, brokenness—and eventual healing.

For the moment, he knows it’s not a good look for a Marine, but he can’t hold it back any longer. He begins to weep.

On a late-autumn morning in 2020, the emotion of that moment and others remained palpable as Hill talked over lattes in the bright, bustling environs of Honeybee Coffee Co. at Kingston Pike and Lovell Road, one of four Knoxville-area Honeybee shops Hill owns and operates.

In a wide-ranging conversation, Hill—whose chiseled, inked physique and sharp jawline belie his easy demeanor and gentleness of speech (think Mike Tyson with a deeper voice)—recounted for the first time publicly his journey through years of buried post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), decades of counseling, and, more recently, powerful experiences with psychedelic therapy. He also reflected on his place in Knoxville’s burgeoning small-business community, where Honeybee—which began as a “hobby” in an Airstream trailer in 2014—has thrived while gaining a devoted fan following in the city Hill has loved since he first arrived as a teen.

An Impulsive Enlistment

Norris Hill was a rising high school junior when his family moved to West Knoxville from Georgia in the mid-1980s. The Southern California native was passionate about sports—especially football. As he grew into a key player for the Farragut Admirals, Hill envisioned competing collegiately, but academic struggles limited his options. As an 18-year-old in 1988, he “impulsively” enlisted in the Marine Corps, packed for boot camp in Parris Island, S.C., and began four years of service that would alter his life in ways he could scarcely imagine—or talk about until almost three decades later.

“I was ready to go see the world,” Hill recalls. “My mom cried for six hours and my dad said, ‘Well, this sounds like the best thing that could ever happen to you.’ Dad had served in the Navy, but I didn’t know much about that. He never really talked about it.”

Hill had long been “unsettled” and vexed by deep questions, “the ‘why’ questions,” as he puts it. Why am I here in this big house with a great family while an orphan kid in Bangladesh is starving to death? Why is there so much suffering? The Marine Corps magnified Hill’s perspective as an American and a global citizen.

“The Marines messed with that in a totally different way,” he says. “It was this whole process of, Who am I becoming? What am I about? What does this uniform represent? We were stripped down, built back up, trained to be the best—better at killing than anyone else in the world.”

Through basic and combat training, the Corps equipped Hill with “discipline, a sense of purpose,” and a depth of camaraderie with young men of varied ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds who became as close as brothers.

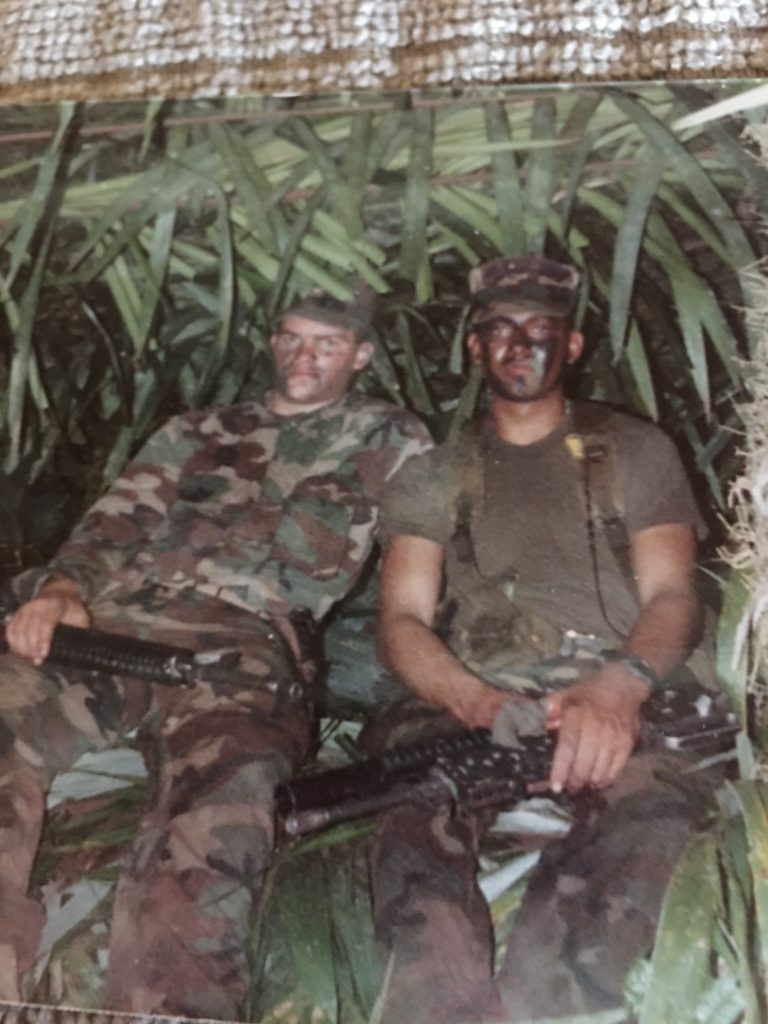

Hill was thrust into unexpected combat in Panama in 1989, when a 72-hour “benign deployment” to guard a fuel base dragged into three months of intermittent jungle fighting after orders came down to remove de facto President Manuel Noriega from power. Several of Hill’s fellow Corpsmen were killed in battle. The experience was a shocking precursor to the action he would see in the Middle East.

‘Always a Wrestling’

Yet it was on that momentous day in Iraq, as he looked into the eyes of the teen soldier clutching the letter, that Hill saw himself in the enemy’s eyes. “I would have wanted to tell my dad the same things if I thought they were taking me away to kill me,” he says. “Let my dad know, and my family, that I love them. Celtic spirituality talks about thin spaces where the distance between heaven and earth collapses. For me, [that moment] felt like a thin space, like something was going on that I needed to pay attention to.”

A fresh perspective entered Hill’s mind: “Humanity is humanity, white or black or African or Puerto Rican. With whatever gifts we have, our role is to take care of each other, if we want to make the world a better place.”

Hill had killed enemy combatants prior to his encounter with the surrendering Iraqi soldiers. Doing so was almost automatic—almost. “There was always a wrestling in me,” he recalls, “but at those moments, usually everything turns off.” Training kicks in. A Marine does his duty.

It wouldn’t be so easy anymore. “I felt like I was digging into this new understanding,” Hill says. “If I believe this about humanity, am I at peace with turning and shooting one of these people? And I was not. Call it a blessing or fortunate or whatever, but from then on, I never had to shoot my weapon at anyone again.”

After Iraq, Hill was transferred to Japan. “It was cool that I was able to put my rifle down for a while.” He left active duty in 1992 and began building a life back in Knoxville that included marriage, a busy job, children, more children (via adoption), and launching his ambitious coffee business.

Pressure and Time

During those post-war years, Hill kept his military service tucked into a sort of emotional footlocker, where the most painful memories were buried too deep to access. He plunged into work, including a 15-year tenure as director of the Provision Foundation, for which he crisscrossed the globe helping to distribute some $75 million of aid in places like Africa and Haiti. “We were able to finance projects for agriculture and coffee and all sorts of stuff. I’m immensely grateful for that.”

Even while the dark memories stayed hidden, the many positive aspects of Hill’s Corps experience often informed his thoughts and actions—especially a level of fearlessness. Case in point: “The earthquake on Haiti in 2010 happened on a Tuesday. I got on a plane by myself, flew to Santa Domingo, rented a car on Thursday and drove to Haiti to help. I was stopped twice by people with guns, and it’s just sort of this, I can do it, you know? Just tell me where to go. There’s no hill that’s too big, no challenge too great.” He and his wife Melissa’s involvement in Haiti led to their adoption of teen son Rivaldo (who would follow in Hill’s footsteps as a standout athlete at Farragut High, this time in soccer).

Military training also aided Hill in launching Honeybee. The business is a labor of love for Hill. It allows him to support Third World coffee farmers, serve up some of the world’s finest coffee, and work closely with his son Aaron, who has developed into a renowned roaster.

“I’m really grateful for the way that Knoxville has wrapped its arms around our business, how well we’ve been received, how well we continue to be taken care of,” he says.

Over time, though, memories of battle took a toll on Hill, from nightmares—he’s under fire, his gun jams, he awakens dripping with sweat, screaming at invisible foes—to anger and edginess. Relationships suffered. Most telling and painful: Hill’s marriage to Melissa unraveled. No parting is one-dimensional, but Hill’s buried trauma was a key factor. “I don’t think most people are equipped to deal with somebody who has PTSD,” he reflects, “and I don’t think most people who have it are equipped to deal with it.” The end of his marriage, Hill says, “popped the cork on my PTSD.”

After experiencing incremental improvement over two decades of therapy—mostly conventional counseling, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), hypnosis and other methods—Hill began hearing and reading about the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs, specifically mushrooms, as a means of helping PTSD sufferers and others to find relief. With professional guidance and care, he underwent an intensive session lasting four-and-a-half hours (followed by several micro-dosing sessions). As wartime memories from Panama and Iraq came into sharp focus, Hill says he was able to see each one in a new light.

Emotions rose. Images sharpened. Tears flowed—and kept flowing. One word kept surfacing: Release. “I started exhaling like in The Green Mile, when [John Coffey] opens his mouth and all that stuff comes out. And it was just ‘release, release, release, release. You don’t have to live like this.’

“When I came to, I experienced a connectivity to the world and to people like I never had before. My perspective on life and death and where I fit in the world and the economy of everything in the culture totally changed. It was deeply, deeply difficult, but I stayed, and I stayed to do the work. It was ridiculously profound and simple at the same time, and the effects have been lasting.”

One of the effects is that Hill thinks more about legacy now. “My mind immediately goes to my two grandkids [Wilson and Sophie]. They’re amazing. I turned 50 this year, and I’m thinking, what does the future hold? I hope the legacy that lives on is this idea of let’s take good care of one another. And I hope at some point, Sophie and Wilson catch a glimpse of that.”

Hill’s progress in overcoming much of his PTSD has tempered his view of the Marine Corps. “The military gave me way more than I gave the military. And I am—it’s taken me a long time to be at peace with this—but I’m extremely grateful.”

Taken together, his progress in recovery has led Hill to stop blaming others for his traumatic memories—the military, people in his life, circumstances—and own his pain, while also forgiving others and himself.

For most of his recovery years, Hill has kept his eye on the path in front of him. But more recently, he is seeing clearly enough to stop and help other wounded warriors on a similar journey.

“It’s tough, getting guys to open up, especially guys that think they’re so tough, mighty and unbreakable, but they’re at a point where, ‘I don’t know why I want to live anymore.’ And once they’re at that point, it’s like, ‘Okay, let’s start processing some stuff.’”

Hill hopes his words to fellow strugglers will hit their mark, not unlike the mark that comes from looking into the eyes of a frightened young soldier and imagining what it must be like to tell your father goodbye forever.

Comments are closed.