Standing in the presence of a creative legend’s memories

It was the summer of 1989. My mom had taken me over to a her friend’s house to visit, as she often did, as they chatted and baked, sipping black coffee. Cooped inside with not much else to do, I wandered through the house in search of a cure for my boredom and came across a very orderly living room—the kind not meant for little hands. There on the coffee table sat a large picture book with black and white photos of landscapes I had never seen: large rock faces seemingly touching the sky, vast canyons, and snow-capped mountains entirely devoid of trees. To this day, I can still remember how transported I felt looking at them.

It turned out that boredom would never again follow me to that house. Each time we visited, I would rush to the living room and flip through the book over and over again, imagining myself exploring its landscapes. I had no idea just what kind of impact it would have on me. A seed had unknowingly been planted. A curiosity for imagery had begun. I found out later that the book was filled with images from a man named Ansel Adams—you may have heard of him—and I was his newest student.

Fast forward to age 15. Borrowing my brother’s Canon A-1 camera, I would pedal to Kroger on Asheville Highway, buy a bag of .99-cent birdseed, then position feeders at varying distances from our bay window to photograph the birds. As a teenager, I hiked the Smokies often, tagging along with anyone who would drive me. By my 20s, I had logged more than 30 states driving alone from the Adirondack Mountains and the wilderness of upstate Maine, to the Grayson Highlands of Virginia and everything in between. Always touting a camera, while knowing very little about how to use it, I documented my travels on Velvia slide film. My fire for photography was in full blaze.

On the way home from one of those such trips, I stopped by an old bookstore in the quaint town of Amherst, Massachusetts. And there, nestled within the wall of large picture books, I found it. The book of my childhood. The book that fueled my desire to hop in a car and drive until my $20 bill ran low, scramble trails I had never trod, hear maple leaves crunch beneath my boots in places I had never been to before, drive down gravel roads that even Rand McNally didn’t show on any map. The one that started everything: The Tetons and the Yellowstone by Ansel Adams. This was the book that taught me to be comfortable being uncomfortable, to push through rugged terrain, and expand my perspective beyond my youthful edges.

Over the next few years, I bought a few other Ansel Adams books and began to see his imagery beyond the pictures themselves. ”When I’m ready to make a photograph, I think I quite obviously see in my mind’s eye something that is not literally there in the true meaning of the word,” he wrote in one. “I’m interested in something which is built up from within, rather than just extracted from without.” I began to understand what he meant. Ansel and his imagery had a great influence on bringing awareness to areas of our country that we now know as Kings Canyon National Park, Denali National Park, and Yosemite National Park. Those images also brought an acceptance that photography could share gallery space with traditional art. Dozens of his books now call my house their home. They gather little dust as I pick them up from time to time seeking inspiration when my creativity is waning.

This past spring, I felt it was time to visit the place Ansel held most dear: Yosemite National Park. He spent many summers there in his youth, found his future wife there, and photographed some of the most iconic images of our time inside this park. I reached out to an old friend, Jim Retemeyer, whom I had met many years prior at the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail at Mount Katadin. It had been years since we had spoken, but as we reconnected, it felt as if no time had passed.

Jim, who at the time of our meeting had just retired from the Air Force, was now a mathematics professor in California. We made plans to hike Half Dome in Yosemite in the fall, and with the help of his significant other, Torri, secured a lottery permit to do so. I’d soon be standing in the same place as my teacher, atop the granite monolith that had been on my bucket list for the last 40 years.

On October 3, I flew into Fresno and made the two-hour drive to the Mariposa Grove entrance of Yosemite. I quickly found that, like our Smokies, Yosemite had been recently ravaged by fire—mile after mile of charred ground, scorched trees, and downed timber. It was beautiful in an eerie way. I turned out toward Glacier Point and wound around the unfamiliar scenes I had first observed in that book at age 8. This moment was 52 years in the making. It felt surreal.

Half Dome loomed in front of me. I found a place to park, then walked a path to a stone wall where I stood feeling as if I were the only person in the world. Fifty other people walked all around, yet this moment felt as if it were just for me. Tears drew, just as I knew they would.

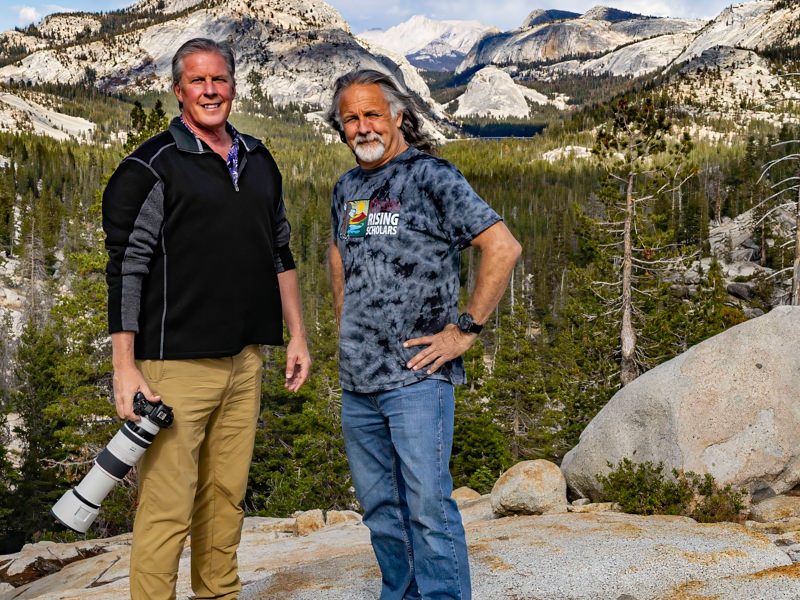

As I brought myself back to the present, I got back in my car and headed to the hotel. A familiar smile and long embrace greeted me, melting away the 29 years that had passed. Jim had traded in his short military haircut for a more fitting Grizzly Adams-esque long grey mane. He introduced me to Torri and together we shared a meal and prepared for our 3:30 a.m. wake-up call the next morning.

We hit the Mist Trailhead at 4:31 a.m. Yosemite at this time of year has a 10 percent water flow compared to the spring snow melt season when all of the waterfalls are roaring, so the “mist” name didn’t apply as we made our way up. We turned our headlamps off at sunrise about the same time we came to the top of Nevada Falls. Over the next couple of hours, we hiked through a beautiful valley, then ascended to the foot of Sub Dome, the most challenging part of the hike for me.

Steep switchback after switchback revealed themselves to us as the top of my quads screamed. I hadn’t waited 40 years to stop now, and thought of Ansel’s words to keep pushing, “A great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed.” I knew the uncomfort of the journey would find its way into the images I would capture at the top.

We came to the foot of the cables that would take us up the final 400 feet of elevation to the summit. “Water bottle!” someone yelled from above, followed by intermittent clanking as it blew past us off the side of the mountain. The cables were steep, and it was a slow slog to the top. Jim, on his 10th ascent of Half Dome, was first, followed by Torri and me, first-timers on this excursion. As the cables neared their end, my first meeting with Jim flashed in front of me. And as we sat at the summit, a breathtaking 360-degree view unworthy of words surrounding us, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed with gratitude as I shared this moment with him. It felt as though a circle had been completed somehow. The moment will forever be cemented in my mind.

On our descent, I ran out of water the last two miles, blew out brand new hiking boots, and destroyed the tips off of some very expensive hiking poles, but nothing could shake the joy I felt. Almost 18 miles, 5200-feet elevation gain, 14 hours on the trail, all done with a friend I met by happenstance almost 30 years ago. And all in a place I had revered since I was a child. It felt as if Ansel had been with us throughout it all.

With four days left in Yosemite, I made the drive to Yosemite Village to the Ansel Adams Gallery, the place where Ansel taught students, developed his images, and lived. I befriended the staff photographer, Courtney Risdon, who graciously took me on a four-hour private tour. We’d end up in the valley shooting various subjects and sharing stories of a legend. When we returned to the gallery, he surprised me with a walk into Ansel’s studio, a once-in-a-lifetime moment. The original darkroom burned down in 1938, along with many never-printed negatives. Ansel himself put the fire out and the studio was rebuilt. I could picture him there giving instruction, encouraging new photographers, and mentoring those with the same burning passion he had until his passing in 1984, the same passion he ignited in me as a boy.

In some ways, I cannot believe it took me more than 50 years to visit this special place. Ansel Adam’s impact on my life was profound and to know I finally stood in the place he stood, experiencing the beauty of what he experienced—with a dear friend along with me, no less—is beyond words. It made me realize that you’re really never too old to explore. Yosemite brought a resurgence of my 8-year-old curiosity. As adults, we often get caught drifting through life, just getting through the next moment. It’s difficult sometimes to be present and curious, like we were when we were kids. But Yosemite reminded me of how good that feels.

Before we left, Jim and I planned our next trip. We didn’t want another 30 years to pass before we went adventuring together again. Next up is Sahale Peak in the Northern Cascades of Washington State, another place I’ve seen photographically and have longed to visit. There’s no time like the present, after all. And I’ll be sure to bring the eagerness and excitement of that 8-year-old kid, sitting on the carpet flipping through the pages of an Ansel Adams book, along with me.

The imagery in front of me comes alive every time I take a photo, and I hear Ansel’s words whisper, “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.”

Comments are closed.