A pandemic affecting people who continually give too much

Regardless how much we may want to help those who are hurting or in need, caring full-time for others can lead to a downturn in a caregiver’s own feelings of vitality, leading to feeling overwhelmed, stressed, ill and depressed. Whether it’s a hospice nurse who loves their job, or a spouse to someone with Parkinson’s who loves their family member, when these caregivers honestly answer the question “how are they?” their loving statements are often followed by attempts to swallow hard feelings and hold back tears.

Compassion fatigue is a term used to describe a state that is experienced by all types of caregivers, after giving to the point of exhaustion and debilitation—with no end in sight. The word compassion means sympathetic pity and concern for sufferings or misfortunes, and fatigue means extreme tiredness resulting from mental and/or physical exertion or illness.

Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue

Cindy Jacquemin, Vice-President of Patient Care at Caris Healthcare—an in-home hospice care program, explained, “signs of compassion fatigue could typically be physical fatigue, (such as) calling off work or not being as interested in work.” According to the National Center on Caregiving, having CF feels like “stress, resulting from continued exposure to a traumatized individual. It has been described as the convergence of secondary traumatic stress and cumulative burnout, a state of physical and mental exhaustion caused by a depleted ability to cope with one’s everyday environment.”

The US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health lists that:

CF is characterized by exhaustion, anger and irritability, negative coping behaviors including alcohol and drug abuse, reduced ability to feel sympathy and empathy, a diminished sense of enjoyment or satisfaction with work, increased absenteeism, and an impaired ability to make decisions and care for patients and/or clients. The negative effects of providing care are aggravated by the severity of the traumatic material to which the caregiver is exposed, such as direct contact with victims, particularly when the exposure is of a graphic nature. This places certain occupations, such as healthcare, emergency, and community service workers, at an increased risk of developing CF and potentially more debilitating conditions such as depression and anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These conditions are known to increase sickness absence, psychological injury claims, and job turnover, and negatively impact productivity.

Symptoms can be deeply emotional as well. Symptoms might include: “crying for no reason,” thoughts of suicide coupled by guilt for having thoughts of abandoning the one needing care, lack of focus or inability to focus—“foggy” thinking, fear of the future loss of the one needing care, coupled by desire for the one needing care to pass—and guilt for having the thought, lack of personal hygiene and proper nutrition.

If any of these symptoms sound familiar, you are not alone.

While most often diagnosed in professionals who work in the fields of mental, emotional, physical or spiritual health, compassion fatigue is by no means limited to professionals. Statistics provided by the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP 2015 show approximately 43.5 million Americans have provided unpaid care to an adult or child in the last 12 months. At $470 billion in 2013, the value of unpaid caregiving exceeded the value of paid home care and total Medicaid spending in the same year, and nearly matched the value of the sales of the world’s largest company, Wal-Mart ($477 billion), as listed in the AARP Public Policy Institute (2015) Valuing the Invaluable.

Mothers and fathers may often be unsung caregivers, caring for children or extended family, to the detriment of their own health. They may also be indirectly caregiving by working to finance the needs of their families, to the detriment of their own needs and personal well-being. A conservative estimate reported by the Family Caregiver Alliance shows that 20% of family caregivers suffer from depression, twice the rate of the general population.

Other types of caregivers include people who give care to those who are incapacitated, wounded, struggling with addiction or veterans of war, narcissists, mentally ill or depressed. People who “carry the world on their shoulders,” giving to its variety of needs and causes can also be considered caregivers. And sometimes, caregivers are overly generous people who admit they “don’t know how to say no,” and give their care to all.

What type of caregiver are you?

Wherever we may recognize ourselves in the previous caregiving scenarios, each of us are caregivers to an extent. As an empowerment coach, I encourage people to assess where they may need to balance their giving to others with their giving to themselves, to live healthier, more joyful and fulfilled lives. So I ask you, are there areas where you give at levels that cause you to suffer: mentally, physically and/or emotionally?

My experience giving too much

Like many of us, I learned things as a child that I needed to unlearn as an adult. I learned by example, that women were to be caregivers to their husband and children and extended families and work job(s) to earn our worth. We either had no awareness of our individual needs, purpose, or feelings, or consciously suppressed them all in order to give our time, energy and bodies to serve. So that’s what I did. However, I held onto a hope that if I continued to give-give-give of myself, eventually, someone—a man, would notice and give back to me. After 36 years of experiencing life that way, my mind and body broke down, and my needs continued to be unmet.

I sat down with a lawyer to create a will and thought about the least inconvenient and most caring way to others that I could commit suicide. I ended a marriage, continued to worked 60 or more hours a week running my high-end design and construction firm, while also taking myself to as many as eight doctor’s appointments a week, searching for ways to heal my body and mind. I struggled mostly in silence, not knowing how to care for myself and feeling unworthy of care. All the women around me continued to behave in the old ways I had, which didn’t work for me—so I couldn’t turn to them for help. And my religious understanding of my role as a Christian at that time, left me feeling that if I had any needs, I was sinning—I was to live my life giving all of myself in service to others. I had no examples of how to be an empowered woman, one who values herself—the creator within her, as just as valuable and important and needed and worthy of care … as all the rest of creation. And that is the lesson I learned from that experience–that I am just as valuable and worthy of care as everybody and everything else.

There is a very good life, beyond the life of an over-giver, and I gladly live to tell about it.

After nearly 15 years of dedicated self-reflection, meditation, prayer, solitary sabbaticals in the deep woods, healers, physical training, a change in diet and plenty of experience, I now enjoy a life that includes lots of good love and healthy, daily doses of self-care. I also created a business called Will You. People meet with me as a source of inspiration and joy. I am a confidential, non-judgmental ally and sounding board, providing intuitive feedback and experiential tools to encourage women and business leaders to make wise choices. My mission is to live a life that inspires, uplifts, and cares for all souls, so we may lead more meaningful, joyful lives.

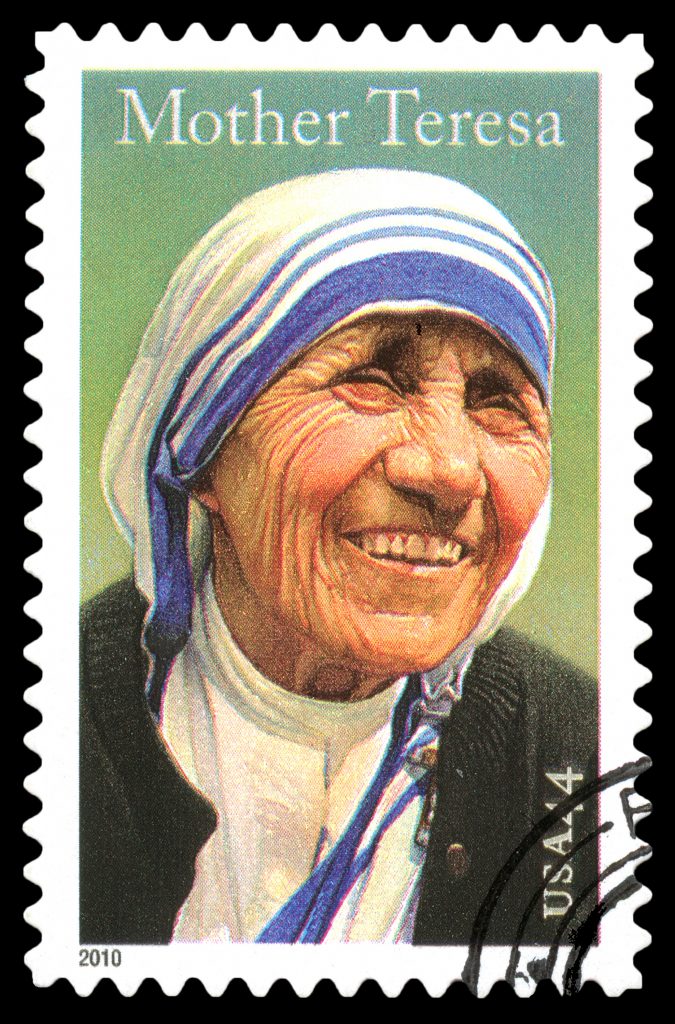

Mother Teresa’s Experience

Over-giving, overwhelm and lack of compassion for ourselves can happen to the best of us. Mother Teresa epitomized caregiving to the world to the exclusion of herself. Unbeknownst to many, she experienced intense personal suffering. “After her death, Mother Teresa’s letters revealed that she spent almost 50 years in a crisis of faith, sometimes doubting the existence of God and frequently feeling His absence in her life. The absence began to be felt around 1948, soon after she began serving the poor in Calcutta, and would last until her death in 1997. As David Van Biema wrote in Time magazine:

In more than 40 communications, many of which have never before been published, she bemoans the “dryness,” “darkness,” “loneliness,” and “torture” she is undergoing. She compares the experience to hell and at one point says it has driven her to doubt the existence of heaven and even of God. She is acutely aware of the discrepancy between her inner state and her public demeanor. “The smile,” she writes, is “a mask” or “a cloak that covers everything.” Similarly, she wonders whether she is engaged in verbal deception. “I spoke as if my very heart was in love with God–tender, personal love,” she remarks to an adviser. “If you were [there], you would have said, ‘What hypocrisy.’”

The deeper cause of compassion fatigue, despair and the “inner hell” experienced by me, Mother Teresa and many others is avoidable if we change our perspective on self-care.

Compassion fatigue and other illnesses are a result of the following three things: a person’s lack of awareness of their own needs, a belief that they are not worthy of having their needs met, and an inability to self-regulate their giving and receiving from themselves.

Compassion fatigue, depression and other mental and emotional disorders are—at least in part, caused by a personal disconnect with one’s own needs. As an empowerment coach, I guide and walk alongside people as they learn to identify their deepest needs and purpose, and nurture themselves in healthy ways. This type of self-care can seem counterintuitive to both our cultural standards of behavior and the way we were raised.

Our personal needs for self-compassion, understanding, acceptance and care is a relatively new concept. While caring for others at the expense of one’s self is often characterized as “heroic,” self-care is often characterized as selfish and/or shameful. This idea is ingrained in our culture, families and religion. Our choice to “sacrifice ourselves to serve others,” may even be labeled “love.”

Over-giving—a nonsensical approach to care.

Sometimes, an analogy can help us see ourselves or our situation differently, so here’s one to which you may relate. When you were a child, did an adult ever tell you that you needed to eat more than your fill because other people were starving? Does it make sense that we should over-eat because others starve? Conversely, should we starve ourselves because people are starving? Should we make ourselves sad because others are depressed? Shall we withhold joy, fun, love, health and care from ourselves (and therefore cause ourselves suffering) because any human, animal, plant or planet is needing care or suffering? This kind of thinking, although prevalent, is neither healthy nor empowered.

According to the National Center on Caregiving, 57% of caregivers report that they do not have a choice about performing (caregiving) tasks, and that this lack of choice is self-imposed. Forty-three percent feel that these tasks are their personal responsibility because no one else can do it or because insurance will not pay for a professional caregiver. Twelve percent report that they are pressured to perform these tasks by the care receiver. And 8% report that they are pressured to perform these tasks by another family member, as listed in AARP and United Health Hospital Fund (2012), Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care.

In each of these situations, caregivers’ own resignation, anger, frustration and overwhelm become fuel for their own compassion fatigue.

Empowered Choices

Teresa’s letters revealed that

she spent almost 50 years

in a crisis of faith…

One step that each of us can take towards feeling our best, is to “fully choose what we choose” to do. This means giving ourselves fully to what we do during the time we do it, with no part of us wishing to be elsewhere. This practice, applied to any part of life is called mindfulness. We are keeping in mind how willing and present we are to participate in our life and choices. Are we “all there?” Or is part of us “checked out?” Or “pissed off” about doing it? By being mindful and choosing to be fully present, we become fully engaged in life. We are in internal agreement about our choices, and no longer feel conflicted, frustrated, stressed, angry or overwhelmed. We feel empowered and at peace in any activity, because our whole self is in agreement to participate—whether we’re caregiving, tree trimming or making love.

The Deeper Antidote

We must compassionately care for ourselves—or risk living the dry and desolate “hell” that Mother Teresa so vividly described. We must compassionately care for ourselves—or risk losing our will and joy to live. To honor the creator and all of its creations, we must compassionately include and care for ourselves as we would care for others.

However, before we can begin compassionately caring for ourselves, we must know that we are worthy to receive care and joy. Worthiness comes when we acknowledge that the power of life that keeps our heart beating, our blood pumping, our lungs breathing and our food digesting, is with and in us. By accepting that we are responsible for caregiving to that life, that power, that God within, we must learn to respect and care for it and therefore ourselves. Knowing this, we can no longer treat ourselves poorly, or deny ourselves and our creator (God) of pure water, healthy food, sleep, sunshine, exercise, and a life worth smiling about.

Three things healthcare managers recommend

For the purpose of this article, the management professionals interviewed in the field of healthcare suggested three methods to provide supportive care to their caregiving staff: learn how to be present with our own family and enjoy time not thinking about work, speak among coworkers or other caregivers about caregiving experiences during extracurricular activities like lunches together or special outings. Third, speak with specialists who can assist you as you learn to better care for your mental and spiritual well-being. Gary Fleenor, Vice President of Human Resources at Caris Healthcare also recommended that caregivers take a step back and recognize the diminishing returns of over-giving. “You have to take it easy sometimes and just sit back and recharge your batteries to be able to maintain your high level of care for others.”

Below, I’ve provided additional recommendations for self-care and caregivers.

First, recognize your worth. The simple fact that you are alive, shows that you are worthy of being here, in this body at this time (as this can be instantly revoked). You are here, and you are deserving of a life that includes care and joy. Each of us can learn to accept and appreciate this more.

Second, mindfulness. Check in with yourself. Are you really taking care of you? Take at least 15 minutes every morning and evening to care enough to ask yourself how you feel and what you think.

Third, meditation and prayer. Meditation is deep listening. Listen: to your answers, to silence, to nature. Observe and accept them without judgment or criticism. If you feel weak or afraid, ask (pray) for help.

Fourth, be more aware of your food. What one thing can you add or remove from what you eat today that would be best for you?

Fifth, get some exercise. What movement can you do for even a few minutes today that would add flexibility and health to your body and mind?

Last but not least, remember to add joy-filled fun! No matter how much you may accomplish, if you have no time for fun, you will probably feel drained by the end of the day (or before you even get out of bed in the morning!). Begin adding joy now. What can you do for 15 minutes today that’s just for fun? (Note: truly joy-filled choices feel just as joyful the next morning.)

Remember, the best way to avoid compassion fatigue is to recognize, accept and appreciate your own worth. Life deemed us worthy to be alive and read this article today. If it didn’t, it could take us. We can accept that we are worthy of life, care, joy and appreciation of all kinds, and can start feeling better right now. If you would like to learn about ways to better care for yourself, willpower that works, and ways to add healthy joy to life, you can find resources at www.willyou.guru.

If you think you may be experiencing compassion fatigue or depression, contact your health provider. If you’re an unpaid caregiver in the home, options in financial assistance and support may be available to you at www.caregiver.org or by calling 1-800-445-8106.

Comments are closed.