Jim Petress shares how service to country led him on a path through medicine

Standing in the shadow of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., Jim Petress notices another graying man a few steps away and recognizes the familiar black ballcap, the patch-adorned vest, and the somber eyes staring quietly at the rows of names etched into the sloping wall of polished granite.

Petress approaches and greets his fellow vet with two words: “Welcome home.”

The man smiles, nods, and responds in kind.

Almost 46 years have passed since the end of the war in Vietnam—56 years since Petress, a longtime Knoxvillian, shoehorned his slender-yet-battle-ready frame into the USS General LeRoy Eltinge and shipped out to the “sandbox” of Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, to begin two tours of combat in steamy jungles and marshy lowlands. Yet that two-word greeting shared among fellow veterans resonates with them as deeply as if the soldiers had just arrived home this morning.

Welcome. When they hear it, or say it, the bond is instantaneous. Home. In three short syllables, they know: You get me, and I get you.

“It means a lot,” says Petress, who moved to Knoxville in 1990 to work in medical care after retiring from a 26-year career in the U.S. Army that included not only combat in Vietnam, but also stints as a medic, physician’s assistant, battalion surgeon, flight surgeon, and cardiovascular perfusionist (operating heart-lung equipment).

“We weren’t welcomed home from Vietnam then—but that was the time. We have been welcomed home since.” (It’s perfectly acceptable for civilians to offer the same greeting to Vietnam vets, Petress notes.)

Father Figure

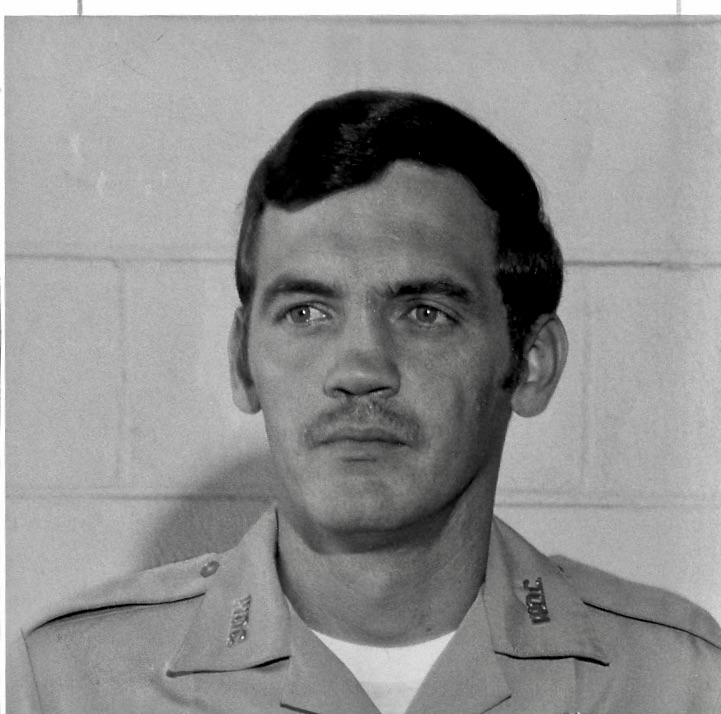

The Pig. Peaches. John Wayne. Peet. Gunner. Those are among the nicknames Petress (sounds like, yep, “peaches”) picked up during a multifaceted military career that began with his eager enlistment at age 17 in 1964.

Life had been anything but peachy for a boy from “a broken home” who was “pretty much on my own at age 14” and often in trouble. Born in Chicago but reared in Jackson, Michigan, Petress recalls a difficult home life that left him fending for himself. Anyone who doubts how profoundly a non-parental adult can influence a child should have met Pete Kelly—a name that still brings a smile to Petress’ face 60-plus years after Kelly, a World War II paratrooper, served as a father figure to Petress in the absence of his own father.

“He was a friend of mine’s uncle, and he was a man’s man,” Petress says of Kelly. “He was tough on me, but I liked being over there because we could fish and hunt. I needed that, because I wasn’t a very good kid. I was able to go back later and tell him, and his children, what a difference he made in my life. At the end of the line, when the Lord says, ‘You ran a good race’—he ran a good one.”

Petress had written in a 6th-grade essay that he wanted to be a Marine someday, but on his 17th birthday when the recruitment office told him he had to be 18 to enlist, “I basically went down the hall to the Army and they said they would take me at 17,” he recalls with a chuckle.

The Heat (and Humidity) of Battle

Petress’ first stop was basic training in Ft. Knox, Kentucky—where he survived marches up and down Heartbreak Hill and was tasked with “dry-shaving” fellow recruits who hadn’t properly shaved before assembling—and then Ft. Benning, Georgia, for Advanced Infantry Training (AIT), jump school, and Ranger school. His last assignment before Vietnam was at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, where he joined the 101st Airborne.

The fighting in Southeast Asia was just beginning to brew when Petress enlisted. His first thought when he heard he was being shipped there was: “Viet-what? Where’s that?” Upon arriving, his thoughts turned to: “I never want to be this hot again.” The steamy conditions were stifling.

Worse, of course, were the casualties of American soldiers that began to mount. During 1965’s Operation Hump in War Zone D—later memorialized in the Big and Rich song “8th of November”—the American losses included Petress’ friend Mike Medley, who was found bayoneted through the hand and shot in the head, indicating that he had been brutally executed.

“Mike was a great guy in a similar situation to me: he had quit high school because he wanted to join the military,” Petress says. “So, you’ve got friends that you lost, or they got hurt real bad. It bothers you.”

In June 1966, Petress and fellow 101st Airborne soldiers took part in Operation Hawthorne, a 19-day battle in which U.S. losses tallied 48 killed and 239 wounded. It was one of the times he most doubted his chances of surviving. “You never want to think that. You go in thinking it’s always going to be somebody else. But when you’re in the thick of it, and it gets really bad, you think, well, maybe it’s my time now.”

Petress did survive and return home. He had wed in 1966 while on leave. Still only 20, he was honorably discharged from the Army in 1968 and returned to Michigan, where a short-lived auto-factory job (“I hated it”) gave way to earning a GED and attending junior college on the GI Bill. He studied nursing and went to work in a local hospital, but it wasn’t to his liking. When a recruiter suggested he rejoin the Army, Petress initially laughed it off but then warmed to the idea. “I kind of liked the structure of the military, so I thought, why not?”

As the 1970s dawned, Petress began phase two of his military career with a focus on medicine. After repeating basic training as the “old man” (age 24), Petress went to the U.S. Army Academy of Health Sciences in Ft. Sam Houston, Texas, for combat-medic training and stayed on as an instructor, having been designated a specialist. He taught Special Forces and Basic Combat medics while working toward a degree in Health Care Management.

In 1978, he applied to the Army’s physician assistant (PA) program, was rejected, spent time in Korea as ward master at the 121 Evac Hospital, applied again, was accepted, and in 1979 began the Army Physician Assistant Program through Creighton University.

After completion, he became a battalion surgeon for the 101st Airborne—his division during Vietnam—and also completed an aviation course at Ft. Rucker, Alabama, to become a flight surgeon.

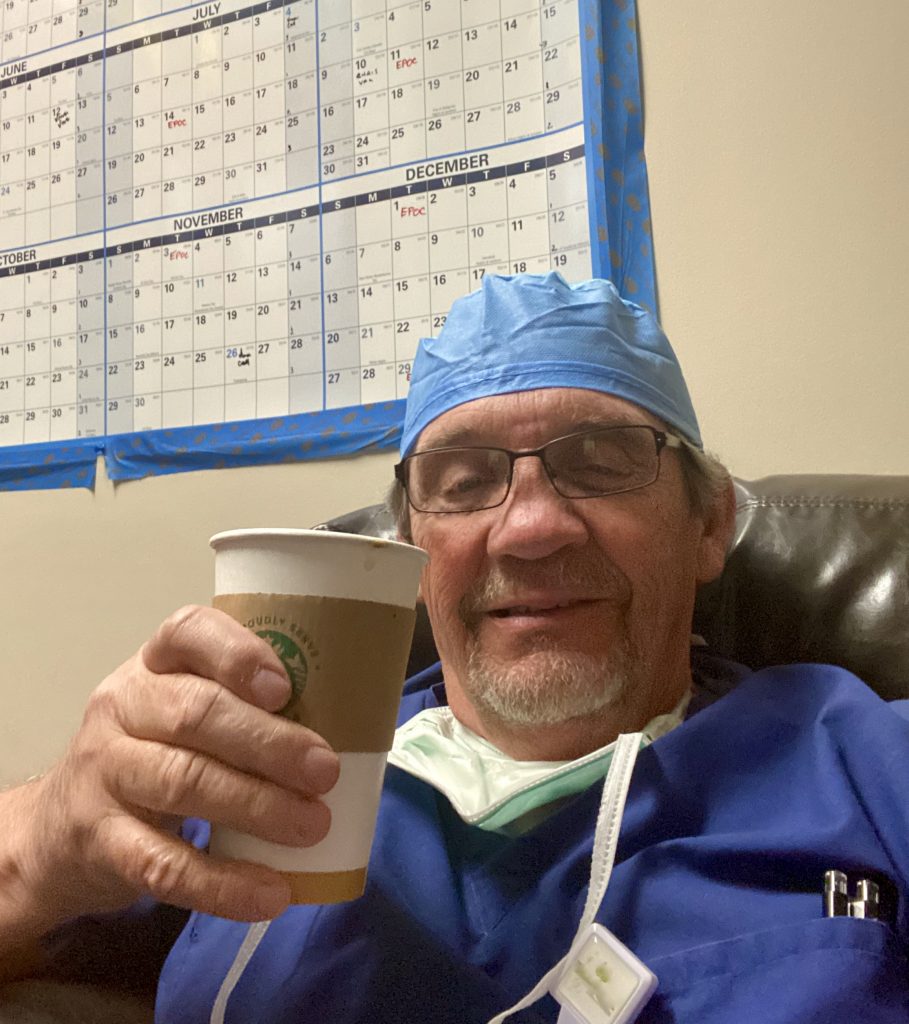

While serving as a PA, Petress became interested in the field of perfusion and completed a course through Penn State University to become a cardiovascular perfusionist. CPs run circulation equipment such as the heart-lung machine during open-heart surgeries and other procedures requiring artificial circulatory or respiratory support. In this new role, he was stationed back at Brooke Army Medical Center at Ft. Sam Houston where he worked until retiring in 1990.

East Tennessee Transplant

Petress had made a number of friends in military medicine, some of whom found their way to Knoxville. When one of them, Dr. Robert Helsel, invited him to consider a job opening here, Petress leapt. He was smitten when he arrived. “What’s not to like about Knoxville?” says Petress, who enjoys the outdoors and the hospitality. “People are a little bit friendlier down here.”

Petress is co-founder (with three cohorts) of Smoky Mountain Perfusion, which provides heart-lung services via Tennova Healthcare. Most of his immediate and extended family now live in Knoxville as well, which affords Petress cherished opportunities to spend time with his children and grandchildren.

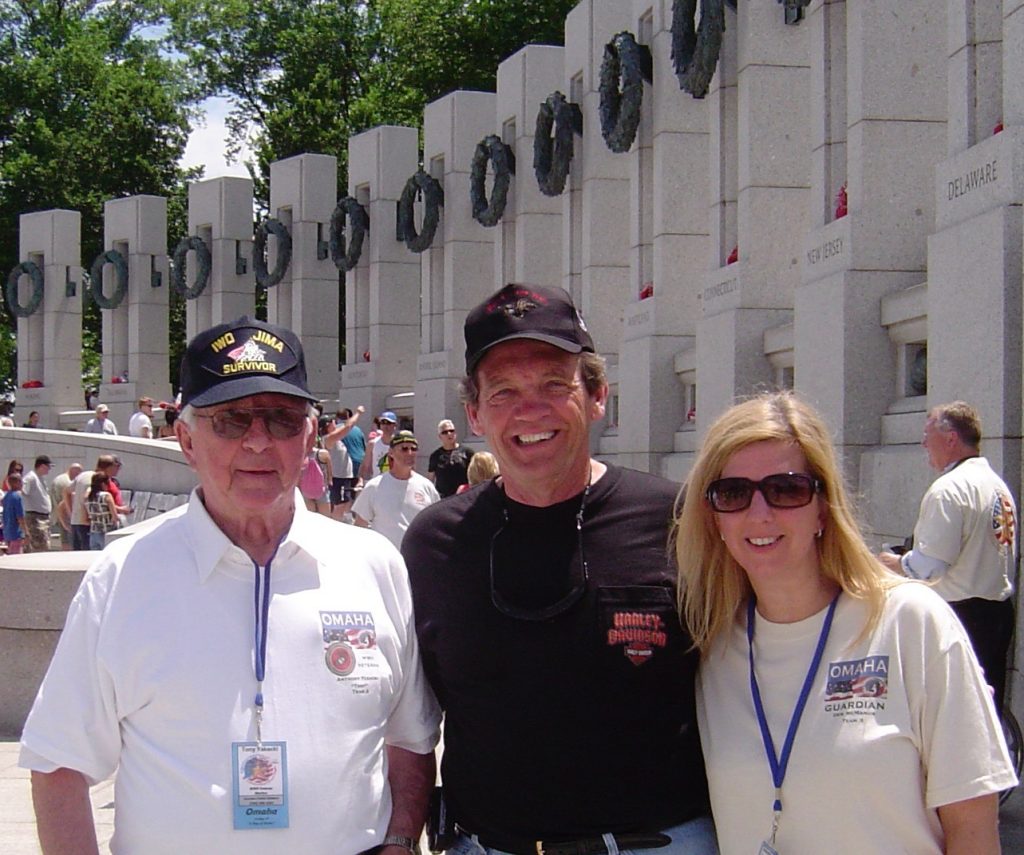

He has kept in touch with his military life by joining fellow vets in cross-country Harley rides that end at the memorial in Washington, D.C. (He typically joins them mid-journey.) He also has sought opportunities to encourage other veterans, especially younger ones from more recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. “They have it tougher than us, in some ways, because they can be in combat on Monday and back home on Tuesday. They don’t have time to decompress.”

‘A Good Man’

As he prepares to retire from the perfusion business in June, Petress reflects on his journey from a troubled youth to an accomplished military veteran, respected medical professional, and friend to many in East Tennessee and beyond.

“I’m very grateful for the country I live in,” he says, “and I’m grateful to the military. I’m a high school dropout who got two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s. It was all because of the military. They gave me the life I have today and the friends I have. We are blessed as a nation, even during difficult times. I’m very grateful for this community. I’m thankful to live in Knoxville, where people appreciate what they’ve got.”

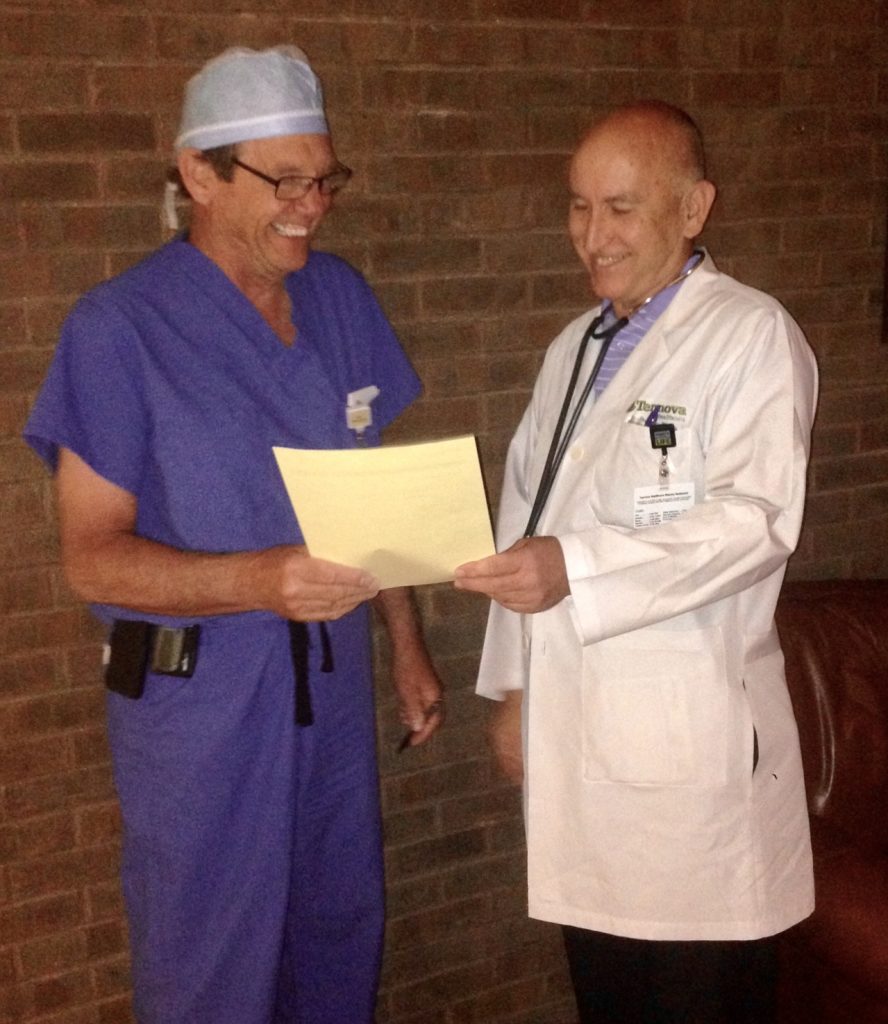

Among the friends Petress values is Richard Briggs, M.D., a longtime, prominent Knoxville heart surgeon who now serves as a state senator in the Tennessee General Assembly. The feelings between them are more than mutual.

“Jim is a perfect example of how a patriotic young man can enter the military to serve our country, take advantage of educational opportunities, and leave with skills to benefit him and the community,” Briggs says. “He exemplifies the military creed of duty, honor, and selfless service to our country. I have known Jim for 35 years. I have the highest respect for him as a fellow soldier and as a colleague in the operating room saving lives. He is simply a ‘good man.’”

Reflections in The Wall

Petress has a serene disposition, laughs easily, and is able to reflect on his service in Vietnam with a philosophical perspective. The only times his voice catches and his smile fades are when he talks about visiting the Wall in Washington.

“Shew. That’s tough. That is very tough. It’s…surreal,” he says of the monument that opened in 1982, bearing more than 58,000 names. “When you look at a name and you realize you were with him, it’s…” He pauses and sighs, adding, “Every time I go, I look for my friends.”

Petress appreciates the statue of three soldiers across the plaza (added in 1984), looking toward the granite wall that memorializes their fallen comrades. They remind him of his time walking side-by-side with brothers in battle.

“I was also very happy to see them build one for the nurses,” Petress says of the bronze Vietnam Women’s Memorial, added in 1993. For Petress, the symmetry between military and medical is especially poignant, since his career has spanned both realms.

As he looks into the caring eyes of the nurse kneeling at the front of the statue, he can almost hear her whispering to the bandaged soldier in her arms: “Welcome home…”

Comments are closed.