If George Washington is the “father of our country” and James Madison the “father of our constitution,” Alexander Hamilton, the top aide to Washington in the Revolutionary War, principal author of the Federalist Papers, and the first Secretary of the Treasury of the thirteen United States, qualifies as the “father of our government.” His legacy included a strong central government, a national bank, a tax system, a navy, and a coast guard. Recently, biographer Ron Chernow and a hit Broadway musical introduced him to a new generation of Americans. Born out of wedlock in the British West Indies, orphaned by his mother, and abandoned by his father, Hamilton was also a remarkable lawyer in his adopted home in New York.

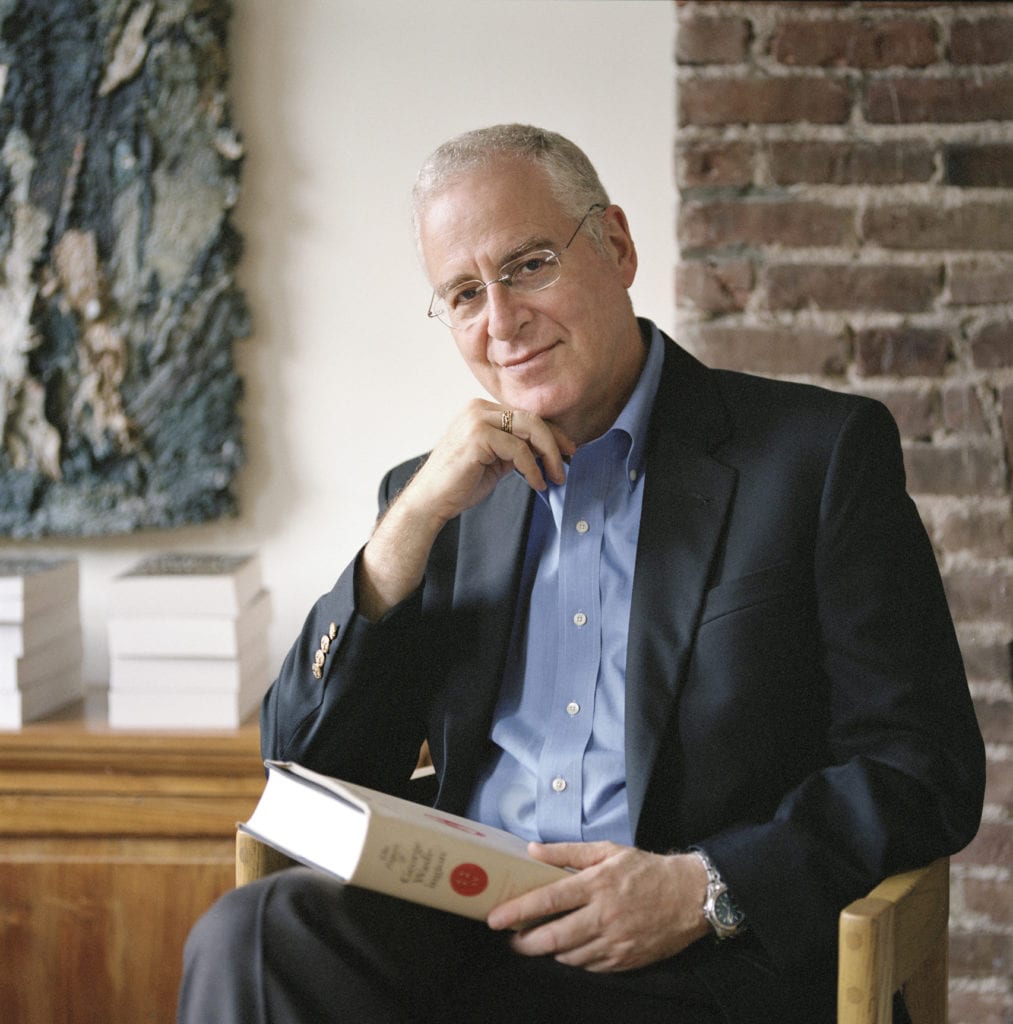

Biographer Ron Chernow is introducing Alexander Hamilton and his legacy to a new generation of Americans. He will be at the Tennessee Theatre on May 7 as part of The Sherri and Baxter Lee Distinguished Speaker Series. The event is sponsored by Lincoln Memorial University Duncan School of Law and the East Tennessee Historical Society.

Primarily a civil practitioner, Hamilton participated in two high profile criminal cases. The first was a murder case which preceded an important election in New York. On a snowy night in December of 1799, Guliema Sands left her residence on Greenwich Street presumably to meet her fiancé Levi Weeks. Days later her body was found in a well. In what became known as the Manhattan Well Tragedy, Hamilton, still serving as Inspector General of our country’s fledgling army, agreed to represent Weeks despite—and perhaps because of—the public uproar against Weeks. In a stroke of irony, Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s bitter rival, assisted in the defense.

An outraged public distributed handbills, accusing Weeks of impregnating Sands and then murdering her. Sands’ relatives and caretakers, Elias and Catherine Ring, displayed her decaying body on the streets of New York for three days. The indictment charged that Weeks, “not having fear of God before his eyes” and “seduced by the…devil, beat and abused” Sands and threw her into the well to drown. People v. Levi Weeks came to trial at the old City Hall on Wall Street in March of 1800. Crowds, unable to squeeze into the courtroom, stood outside, chanting “Crucify him!” In proceedings lasting past midnight over three days, fifty-five witnesses testified. Cross-examinations of the Rings established that their boarding house served as a brothel and that Elias had likely slept with Sands. Ezra Weeks, the defendant’s brother, offered alibi evidence which was corroborated by a local architect.

When cross-examining Richard Croucher, who lodged at the boarding house, Hamilton held candles to each side of his face—producing a frighteningly sinister image. He then asked the jurors “to look upon the man’s countenance to his conscience.” The transcript implies that Croucher confessed to the crime and then bolted from the courtroom. The jury returned a not guilty verdict in five minutes. Later, Burr claimed that he, in fact, had used the candles, announcing to the jury, “Behold the murderer!” The transcript simply identifies the questioner as “one of the prisoner’s counsel,” Chernow questions Burr’s claim.

“For six hours, he argued for a new trial, contending that a free press served to check abuses of executive power.”

The second case did not produce victory but led to a change in the law of defamation—then a crime. In 1803, Harry Croswell, a newspaper publisher favoring Washington’s Federalists, charged that Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, who won a victory over incumbent John Adams in 1801, had, during the campaign, paid his party’s newspaper editor, James Callendar, to publish an allegation that “Washington was a traitor, a robber, and a perjurer” and that Adams was a “hoary-headed incendiary.” Offended by the story, Jefferson sent a message to his party’s loyalists: “[A] few prosecutions of the most prominent offenders would have a wholesome effect on restoring the integrity of the presses.” In short order, Croswell was indicted for defamation by an attorney general loyal to Jefferson. Hamilton, whose differences with Jefferson during Washington’s administration had led to the creation of the two vying political parties, joined the defense.

At that time, all the prosecution had to do to gain a conviction was prove that the statements were defamatory. Truth was no defense. By 1803, Callendar, the source of Croswell’s story had turned against Jefferson. Just before trial, Callendar drowned under mysterious circumstances. Hamilton had no basis to subpoena Jefferson to testify. The verdict of guilt was inevitable. On appeal, Hamilton sought a change in the law, maintaining that truth should never be a crime. The state legislature, recognizing the importance of the case, adjourned to listen to Hamilton’s presentation. For six hours, he argued for a new trial, contending that a free press served to check abuses of executive power. Otherwise, he asserted, in a pointed reference to Jefferson, “the most zealous reverers of the people’s rights, have, when placed on the highest seat of power, [can] become their most deadly oppressors.” A reporter wrote that there was “not a dry eye in the house” at the conclusion of Hamilton’s remarks. Counsel for the prosecution called his legal powers the “greatest . . . .this country has ever produced.” Nevertheless, the four panel judges split 2-2, thereby upholding the verdict of guilt.

In the notorious 1801 election, both Jefferson and Burr received 73 electoral votes. The incumbent Adams had only 65. Although it was commonly understood that Burr was to be vice-president, he declined to yield to Jefferson. Under the rules of the electoral system in place prior to the ratification of the 12th Amendment, each member of the Electoral College cast votes. Because no distinction was made between the votes for president and vice-president, the decision was to be made by the House of Representatives. Although incoming members of the House would give the Jefferson’s party a 68 to 38 advantage, the lame duck membership, where the Federalists had a 60-46 majority, had the duty to choose. The sixteen states had one vote apiece, so 9 votes were necessary to win. While his party all voted for Jefferson, most Federalists voted for Burr, resulting in a two-way tie for 35 consecutive ballots. Despite his party differences with Jefferson, Hamilton denounced Burr, convincing James Bayard, a Delaware Federalist, to switch to Jefferson on the 36th vote.

After sworn in as President, Jefferson had no use for his disloyal vice-president. In an effort to recapture his political clout, Burr ran for governor of New York. Hamilton worked to assure his defeat. Burr demanded a duel. Chernow wrote that on July 11, 1804, while Hamilton fired into the air, Burr shot to kill. Thus, Hamilton did not live to see his state adopt truth as a defense to libel. In the 1964 landmark case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court ruled that in order to prevail on a claim, a public figure must prove the statement to be false, defamatory, and maliciously made—much as Hamilton had argued 160 years earlier.

Comments are closed.