The Volstead Act brought with it a host of unintended consequences, causing leaders to question whether they made the right choice.

There is Murphy’s Law, “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong,” and then there is its first cousin, the Law of Unintended Consequences. The latter law might be defined as any attempt to solve a complex problem that creates unanticipated and often undesirable results. Almost 200 years ago, a London paper expanded on these concepts with a Portuguese proverb, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” So, in order to rid the country of the physical and social ills related to the use and overuse of alcohol, America endeavored upon The Great Experiment. There were consequences.

The prohibition movement actually began shortly after the conclusion of the Civil War. Organizations like the Prohibition Party, the Anti-Saloon League, and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union launched a grassroots effort to ban all forms of booze throughout the country. Influenced by the death of her first husband who had suffered from severe alcoholism, Carrie Gloyd became a passionate activist for prohibition. She soon met and married David Nation, a minister and attorney, and the couple eventually moved to Kansas, where Carrie Nation started a local branch of the WCTU. When her peaceful efforts failed to persuade those in the saloons to abstain from their bad habits, she turned to more forceful means. Undeterred by a growing number of arrests for her destruction of the inventory of local saloons, she adopted a hatchet as her weapon of choice, singing hymns, praying, and gaining popular support as she destroyed huge containers of the “evil alcohol” in her targeted taverns. A heroine to many and a nemesis to others, her death in 1911 did not slow the nation’s movement toward outright prohibition. By then, a veritable army had joined in the cause.

The founders of the 1789 Constitution, however, had purposely developed a cumbersome process for any amendments to their historic document. The House and the Senate had to first pass a joint resolution for consideration by the states, and then three-fourths of the states had to vote in favor of ratification. In 1917, during the First World War, Congress completed the first step with overwhelming votes in each chamber. The popularity of the measure extended to the states. Not long after the war’s end, Nebraska became the 36th of the then 48 states to vote for ratification of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. Only Rhode Island and Connecticut had voted to oppose. The National Prohibition Act, the enabling legislation essential for the enforcement of the amendment, had the strong support of House Judiciary chair Andrew Volstead and passed easily in Congress. Even though President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the measure, the House and Senate had more than the two-thirds necessary to override, and, on January 16, 1919, adopted as the law of the land what came to be known as the Volstead Act.

The law prohibited the production, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors, defined as containing 0.5% alcohol or more. There were loopholes. First, the act did not become effective until after one year, permitting stockpiling by the customers who could afford to do so. For example, when the Wilsons vacated the White House at the end of their term, they took their supply to their new residence; President Warren Harding, Wilson’s successor, moved in with his own stash. Whether local or national, politics and alcohol had often worked hand in hand. Second, the act did not prevent the actual consumption of alcoholic beverages, allowing wine and cider manufacturing for home use—much to the relief of the mountaineers in East Tennessee and rural areas throughout the country. Finally, there were exceptions for alcohol in medications prescribed by physicians, alcohol distributed by pharmacies, and alcohol used for religious purposes, including churches and synagogues. One authority on the subject claimed that the prosperity of the Roman Catholic Church, wine being a part of the sacrament, reached new heights in the decade following the Volstead Act—probably not a coincidence.

There were critics of this Great Experiment. Winston Churchill, well known for his love of scotch, famously described the American law as “an affront to the whole history of mankind.” Then there were these unintended consequences. When the breweries and distillers in the United States closed operations, the production and sale of alcoholic beverages surged in our bordering countries. Mexico and the islands of the Caribbean were among the areas that prospered. Canada benefited the most. “Rum running” took place with impunity on the Detroit River, which serves as a boundary from our neighbors to the North as far east as Lake Erie. The lyrics of a rhyme written in these times reflected our country’s budding relationship with the Canadians:

Four and twenty Yankees, feeling very dry, Went across the border to get a drink of rye. When the rye was opened, the Yanks began to sing, God bless America, but God save the King.

Bootleggers became commonplace in the 1920s. Speakeasies, wide open to women, replaced saloons where men had once had almost exclusive reign. No self-respecting women would be caught dead in the old taverns and bars, but the secret nature of the speakeasy, so named because the patrons were warned to “speak easy” so as not to alert law enforcement of their whereabouts, changed that. New York alone, which was loathe to assist in the enforcement of the prohibition law, had as many as 100,000 speakeasies, according to one source. One authority on the subject estimated that 60 percent of the nation’s local law enforcement officers had violated the Volstead Act and that accepting bribes to turn heads to illegal operations was commonplace within the profession.

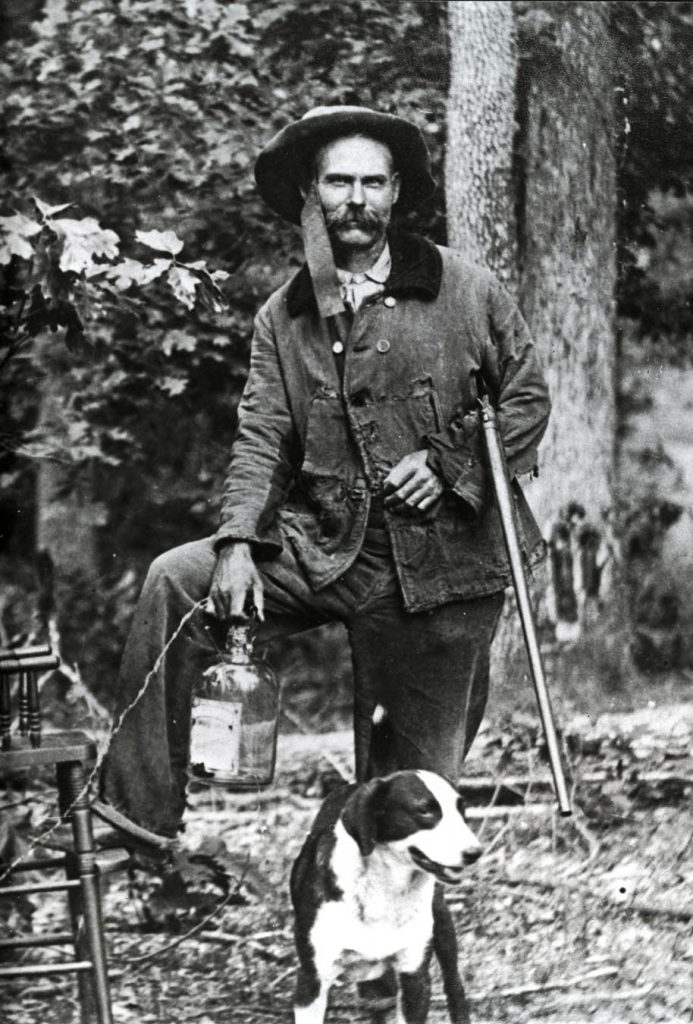

Terms like “bathtub gin” made in the home and, of course, “moonshine,” manufactured by moonlight in remote areas, became a part of the American vocabulary. Further, grocery stores had a difficult time keeping concentrated grape juice in stock. The packaging had warning labels: “Do not store in a jug for more than 20 days in order to avoid fermentation.” The companies that sold the product might as well have provided the recipe for table wine.

The prohibition era served as a boon for some in the medical and pharmaceutical professions. In just the first six months of the Volstead Act, 15,000 physicians and 57,000 pharmacists acquired licenses to prescribe and sell products containing percentages of alcohol far greater than permitted by the new legislation. To illustrate the impact of these exceptions on pharmacies, during the decade after passage of the 18th Amendment, Walgreen’s experienced remarkable growth, expanding from 12 to 525 stores across the country.

Federal law enforcement, which was understaffed, underfunded, and overwhelmed by their new responsibilities, did their jobs as best they could. By the second year of the Act, over 20,000 prosecutions took place. That number increased substantially every year, but still only scratched the surface. In Chicago, Al Capone became both wealthy and famous. Organized criminal gangs like his, previously limited to gambling and prostitution, found a new and better source of income through illegal sales of alcohol, and they often fought each other for “territory.” Incidents like the 1929 Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, when seven of “Bugs” Moran’s rival Irish North Siders were lined up against the wall and shot by four alleged Capone men, two of whom wore police uniforms, changed the minds of many of the Americans who had supported prohibition.

The influential John D. Rockefeller, Jr., an early proponent of the Great Experiment, altered his position on the issue by the end of Herbert Hoover’s presidency. In 1932, he wrote that “the law had made otherwise good citizens criminals and had encouraged disrespect for police authority.” Franklin Roosevelt, the Democratic challenger to Hoover in that election year, announced in his campaign that he favored repeal of the 18th amendment. Hoover was hesitant on the issue. After Roosevelt’s convincing victory, the Cullen-Harrison Act increased the alcohol content of Volstead from 0.5% to 3.2% as to beer and wine, adding jobs to the depressed economy. After signing the bill, FDR announced, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”

On December 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment, adopted by Congress and the states in the same way as the Great Experiment had become law, repealed the 18th Amendment, the first time in United States history—and so far, the last—that a constitutional amendment has been overturned.