Chris Albrecht serves his fellow veterans long after the battle ended

One of Chris Albrecht’s all-time favorite quotes—more than that, a guiding maxim, a life principle, the impetus behind many of his passionately persistent endeavors across the Knoxville community—is variously attributed to the ancient Egyptians, to prolific American author Ernest Hemingway, and to elusive English graffiti artist Banksy.

No matter where it originated, the sentiment abides near the front of Albrecht’s mind and heart as he seeks to salve the internal wounds of battle in the lives of his fellow U.S. military veterans. For them, the fog of war has long lifted, yet the fog of painful, often quietly debilitating memories clings like mist on a Smoky Mountain morning.

The quote, in essence, is that every person dies twice: the first when they stop breathing, are buried in the ground, and a headstone is placed on the grave; and the second when someone speaks the person’s name for the last time.

Albrecht’s desire to keep names and legacies alive finds expression in his leadership roles within two area organizations: the Capt. Bill Robinson Chapter 1078 of the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), where Albrecht serves as public information officer (PIO); and the United Veterans Council of East Tennessee, a more broadly focused veterans’ organization which Albrecht helped to found and where he serves as president and PIO.

Among many meaningful ways Albrecht helps to bless the lives of those who have served America in the military, three programs stand out to him: one, a regular series of no-cost veterans’ breakfasts throughout the community that provide much-needed connections and build life-giving camaraderie; two, Salute to Tennessee’s Fallen, a relatively new traveling memorial honoring Knoxville-area service members who have lost their lives since 9/11; and three—the most widely known—an annual one-day effort called Wreaths Across America (WAA).

Voices for the Voiceless

That third initiative is perhaps the most special to Albrecht, partly because of its fast-growing impact in the community. Each Christmastime (in 2023, the date will be Saturday, December 16), volunteers “show up by the hundreds” at Knoxville’s three veterans’ cemeteries, place a wreath at each headstone, and then—in a gesture that touches closest to the meaning of Albrecht’s go-to quote—speak the name of the veteran aloud.

They say each name, and if Albrecht has anything to do with it, it won’t be the last time.

The scope of the wreaths initiative has become almost staggering: the three veterans’ cemeteries hold some 19,000 graves, and “the past two years we’ve had enough wreaths to cover all of them,” Albrecht says with a touch of wondrous gratitude in his voice. “This has rapidly become a Knoxville holiday tradition. More and more people are willing to support it, mostly by word-of-mouth.”

In the days leading up to each wreath-laying Saturday, Albrecht’s anticipation builds. “When I see those three or four semi-trucks pull into the lot [shipped from Maine], it’s a big deal. I’m so pleased I can be a part of it.”

Two of the cemeteries are operated by the state of Tennessee. The one on John Sevier Highway is the area’s “active” resting place, with 15 to 20 military funerals each week. The other is sloped along Lyons View Pike near Northshore. A third, the National Cemetery on Tyson Street Northwest, dates to 1863 during the Civil War; its approximately 9,000 plots include many prominent Knoxvillians, among them General Robert Neyland.

“We like to see every veteran honored,” Albrecht says, noting that individual and corporate donations provide the funds to make that happen. Someday, he will be counted among that number. “I plan to be buried at the John Sevier Highway cemetery, and I hope somebody places a wreath at my headstone and says my name out loud.”

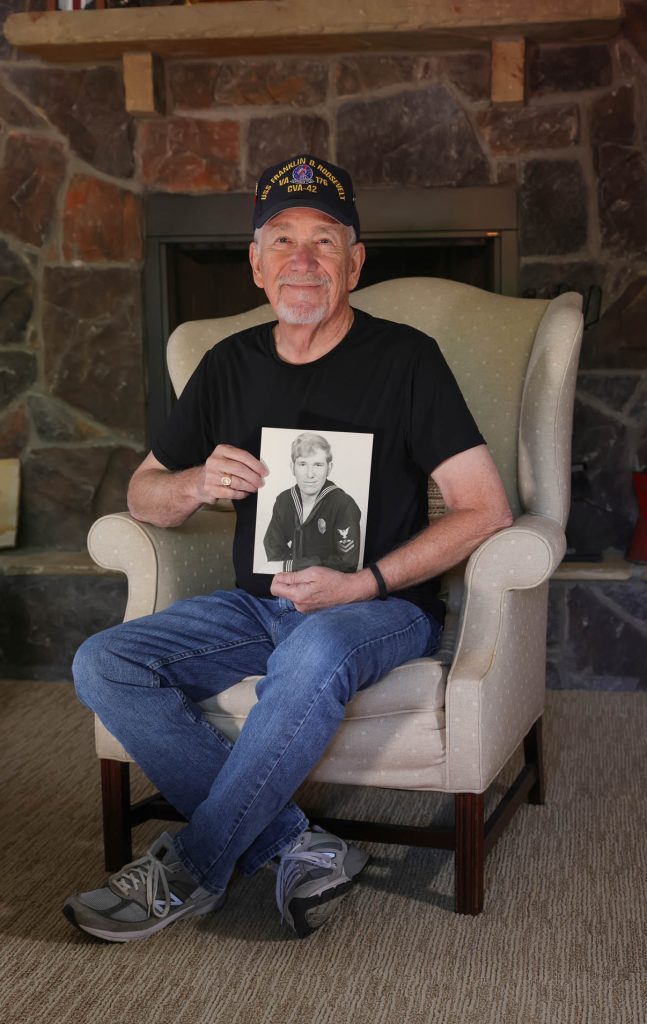

While Albrecht describes his own background and military service as “unremarkable,” it is insightful to trace the path that led him from an Ohio boyhood, to four years in the U.S. Navy during the late 1960s and early ’70s, to a varied professional career including landscape horticulture and radio, to a move to Knoxville when his wife accepted a job at UT-Knoxville, to becoming an integral, highly valued member of East Tennessee’s veterans community.

Growing up in the capital city of Columbus and graduating from high school in 1967, it was natural for Albrecht to enroll at The Ohio State University. Problem was, “after the better part of my freshman year, I realized I was not, shall we say, college material at that point in my life,” he says. “At that time, Vietnam was raging, and I knew I would be draft bait, so I enlisted in the US Navy.”

His father and uncle had each served in the Navy during World War II. “When I came home and announced I had dropped out of school, my dad was not a happy camper,” Albrecht recalls, “but a few weeks later when I said I was joining the Navy, he said, ‘That’s the best decision you could ever make.’”

As many fellow vets will attest, entering the service at age 19 accelerated Albrecht’s maturation. “I had been a horrible student in high school and college; in the Navy being a horrible student wasn’t an option,” he says. “By the time I got out and my active duty ended [in 1972], I was an EF second-class petty officer, equivalent to a sergeant in the Army, which was as high as I could have advanced in four years.”

‘One Misstep . . . World War III’

In between, after boot camp at Naval Station Great Lakes north of Chicago, Albrecht was sent to aviation electronics school down South in Millington, Tennessee, and then assigned to a squadron at Naval Air Station Cecil Field just west of Jacksonville, Florida, where he served as an aviation electronics technician.

At Cecil Field, he worked on aircraft including the LTV A-7, a carrier-capable light-attack bomber developed in the early-1960s. Later, he was transferred to Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where he performed electronics tasks on the A-6 Intruder, the first Navy aircraft equipped with an integrated airframe and weapons system. (Cutting-edge stuff for its time.)

In layman’s terms, Albrecht says he “kept the radio working so the plane could fly. I was not a warrior; I was a cog in a multimillion-dollar weapons system.”

During his four years, “I spent more time at naval air stations than aboard ship,” one notable exception being the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Midway-class aircraft carrier that traversed the Mediterranean Sea. “There was this thing going on that most people have forgotten about called the Cold War,” Albrecht deadpans. “We spent our time playing what might flippantly be referred to as a game of ‘cat and mouse’ with the Soviet air force and army.”

The job did not entail direct combat, but tensions were high nonetheless. “One misstep on anybody’s part could have started World War III,” Albrecht says.

Despite being in the camp of “Vietnam-era, but I never went to Vietnam,” Albrecht knew many contemporaries, including a handful from his high school, who saw combat in-country, some of whose names are now etched into the wall of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Upon completing four years, in January of 1973 Albrecht returned to Ohio State on the G.I. Bill and earned a degree in landscape horticulture, only because “it sounded like an interesting thing to learn about. I have never been disappointed about that.”

The war in Vietnam was even more pitched. “Walking across campus you could tell who the veterans were. You might make eye contact and nod, but that was it. Being a vet then was a real low-profile thing.”

After college, Albrecht worked in landscape-design sales and installations, but over the years he also engaged his communication chops in the radio industry, providing broadcast management, working with sales staffs, and doing “thousands of voiceovers for radio and TV commercials.” (He’s got the richly resonant voice for it, to be sure.)

At Home in Knoxville

For a chunk of his broadcasting career Albrecht lived in Manhattan, Kansas, where his wife, Mary, whom he had met at Ohio State, was a professor and department head at Kansas State University. In 1996, Mary was offered a role as a professor and assistant provost at UT-Knoxville, which brought the couple to our fair city.

The Albrechts have one son, who is now grown, married, living in Knoxville, and the father of a young daughter. “We’re awfully proud of our son,” the elder Albrecht says, “and our granddaughter has me wrapped around all of her fingers.”

One key to acclimating to Knoxville when he first arrived was being a member of Optimist International and taking part in the local chapter’s activities. It was only about eight years ago when a friend and fellow vet invited (see also: challenged) Albrecht to become involved with Vietnam Veterans of America. At first, he demurred. “I reminded him that I had not served in Vietnam.” The friend persisted, noted that Albrecht had been in uniform during that era and had followed orders; this was another opportunity to continue in the vein of serving.

“My first step was to become a member of the VVA’s Capt. Bill Robinson chapter,” Albrecht says. “We have about 325 members who meet once a month. We’re not just a bunch of old farts telling war stories. We can look each other in the eye and say, ‘I’ve been there and done that.’ We talk about life, grandchildren, projects in the community. Camaraderie is the key thing there.”

Camaraderie. It’s a word that Albrecht returns to several times during the conversation. “The friends that I’ve made, the camaraderie we share, to me is so vital,” he emphasizes. “Working together, standing shoulder to shoulder with brothers and sisters, means the world.”

He points to studies that indicate more than 20 veterans commit suicide every day in America. “It’s absolutely tragic. When a veteran is feeling alone and isolated, they are more susceptible to those thoughts. We like to think we are doing things to combat that. That sense of camaraderie that we are building is nothing but positive for mental health.”

A supportive larger community also plays a critical role. Albrecht had already long-since fallen for Knoxville before he became involved on the military front. At that point, his appreciation only grew. “I discovered that this is an extraordinarily veteran-centric community,” he says. “I can wear a vet’s hat into Kroger or Home Depot, and inevitably somebody’s going to say ‘thanks for your service’ and start a conversation. Knoxville is special that way.”

The same is true among local news media, he says. In his publicity roles with the VVA and United Veterans Council, Albrecht interacts frequently with reporters and editors. “They have all been very supportive of what we’re doing.”

Reflecting on both his own time in the Navy and the intervening years, Albrecht remains humbly grateful.

“The military experience changed my outlook altogether and pointed me in the right direction,” he says. “I don’t regret any of that time. As a new enlistee, I would have rather been home with my friends goofing off, but I was making a lot of new, lifelong friends and having experiences that I would never wish away.

“When all is said and done, I’m proud of my time in uniform.”

He is at least as proud of—and deeply thankful for—the opportunities he continues to seize to give back to his brothers and sisters across East Tennessee. To honor, to respect, to support, to foster camaraderie.

And to keep on speaking the names.