Good times, good music, good food, and bad smells

The lights went on before 4 a.m. that early August morning as Marcus Loudermilk prepared to drive the 150 miles from his Henagar, Alabama, farm to the Market House in the center of downtown Knoxville. He loaded his vegetables the night before to depart well before daybreak. His 23-acre farm on top of Sand Mountain was infested with rocks, but had surrendered enough corn, squash, potatoes, onions, and tomatoes to, hopefully, make the four-hour trip up U.S. 11 worthwhile. His teenage boys, Ira and Charlie, promised to go on this trip, but he let them sleep until just before leaving time. Excited to return to Knoxville, they had trouble going to sleep Friday night.

When called to “load up,” Ira grabbed his mandolin and Charlie clutched the guitar he had slept with as they got in the family truck. The boys had made this trip many times and knew there would be dead time and opportunities to practice their instruments and perhaps sing to customers buying their family produce. They were learning to harmonize on the country gospel songs they had heard on the radio and in church.

Truck farmers like Loudermilk lined the east and west sides of the Knoxville Market House and diagonally parked with the backs of their trucks pulled to the sidewalks to display their goods to shoppers moving along busy Market Street. By 10 a.m., commerce was brisk on either side of the Market House; the indoor stalls were stocked with bread and bakery items, poultry, fish, meats, vegetables, and flowers. In the August heat of 1942, the Loudermilk family was only one of hundreds of farming families throughout East Tennessee and surrounding states to earn a living selling their products in or around the Knoxville Market House. They would spend their day in Knoxville and depart when their truck was empty and their pockets full.

A few years after the Loudermilk boys would pick and sing in the back of their daddy’s vegetable truck, I discovered the Market House on what is now Market Square. When I first visited in the 1950s, it was a happening place, part farmers’ market, grocery store, and shopping mall all wrapped into one. I remember walking through the giant doors on the south end of the great, ornate building where Union Avenue intersects with Market Street and smelling the pungent bouquet of fish mixed with the potent odor of neglected meat. My mother shopped there and bought her fish from Turner’s Fish Market, which was in a stall near the south or Union Avenue end. There were several other fishmongers and butcher shops with their goods displayed on counters. Mr. Turner always wore a long white apron, soiled with fish blood and slime. I assumed he smelled like fish everywhere he went. The stalls throughout the Market House were filled with produce, and my mother would always buy okra for her okra gumbo—which turned me against the strange vegetable for life. Today, it is still about the only thing I will not eat. I remember the Market House as very crowded with ladies in housedresses and big straw hats and men in suits buying food to take home, laughing, and talking about adult stuff. As a kid, the true fascination for me, however, was on what was outside the building.

While in elementary school, I spent a great deal of time downtown and have fond memories of many of the buildings and stores that no longer exist. When I entered the first grade at Lincoln Park School on Chickamauga Avenue, my mother became a real estate agent on the 15th floor of the Bank of Knoxville building at the corner of Church and Market. Occasionally, I would visit her office and enjoyed throwing office supplies out the window to see how long it would take them to fall to Market Street. In my youth, I walked the streets of central city looking for entertainment and observing the activities of shoppers. I was like a kid in Wonderland. It was a different time; I guess my parents did not feel that I needed an escort.

One of my regular haunts on Market Square was the Kinney Shoe Store because it had a “shoe-fitting fluoroscope” where you could stand on a box and look into a scope and see the bones in your feet. In the early 1950s, X-ray was the rage and, thanks to Thomas Edison, fluoroscopy was a type of X-ray image you could watch on a monitor like a movie. I learned to jump up on the box and look at the bones in my feet when my mother would take me to buy Buster Brown shoes. No other store had fluoroscopy, and the Kinney Shoe Store on the east side of Market Square was crowded with children waiting their turn to look at their foot bones. The largest family-owned shoe store in America, Kinney eventually closed in 1998 leaving as a survivor its subsidiary division, Footlocker. My mother always bought me ugly Buster Brown shoes because my pediatrician told her I had high arches and I should never wear anything but a lace-up shoe. My family would sing the Buster Brown jingle, “Bark, bark. I’m Buster Brown, I live in a shoe. That’s my dog, Tige, look for him in there, too.” After it was discovered that excessive exposure to X-rays was harmful, the “shoe-fitting fluoroscope” was discontinued, but only after I had logged more time on the device than probably any other child in America. The first thing I did when I left the family home was buy a pair of loafers, and I never wore a lace-up shoe again until I turned 60 when my feet finally started to give out, probably due to wearing loafers against the advice of my baby doctor and the biological effects of overexposure to X-rays. I expect my feet might fall off any day now.

I loved visiting Mayo Seed Company on Wall Avenue at the north end of the Market House at Easter time. Hundreds of yellow baby chicks (including many dyed all colors of the rainbow) would run around in an enclosure with a ramp and sliding board into a tub of water. It was fun to watch them interact, climb the ramp, and slide down the sliding board. One year, I bought one of the chicks and took it home to shock my mother. Mayo Seed Company, founded in 1878, eventually became Mayo Garden Center and spread to all areas of the county.

As a boy, I would always visit Bell Sales Company on the east side of the Market House because that’s where the action was. Mr. Sam Morrison, the owner, was my friend and always had a stack of records for me because he knew and understood my taste in music. I could spend hours in Mr. Morrison’s store, which was small but had a great sound system. He would let me play records on a turntable and the music would play through speakers in the store as well as an outdoor speaker over the front door, entertaining the farmers and shoppers along the street with records by Big Joe Turner or perhaps Little Richard. When I walked in, he would say, “Bobby, I’ve got something good for you, come with me,” and he’d take me to the back of the store and hand me five or six choice records. I bought a lot of novelty and R&B records from Mr. Morrison and I still had them until recently when I sold my 45-RPM record collection because I ran out of room to store it.

Peter Guralnick in his book, “Last Train to Memphis,” reports that in August 1954, RCA field agent Brad McCuen stopped by Bell Sales to take orders from Mr. Morrison for new recordings and there was first exposed to a Sun recording by a young artist named Elvis Presley. The East Tennessee area was considered by RCA to be a “cow bell” area because any record that became a hit between Bristol and Knoxville typically went national. Morrison explained to McCuen that he was selling out a box a day of “That’s All Right, Mama” by Presley to both country and R&B fans along Market Street. McCuen reported the rising star and his surprising appeal in Knoxville to RCA executives, which led to the buyout of Elvis’s contract with Sun Records and the ultimate release of “Heartbreak Hotel” on RCA. Sam Morrison was not only good to me, but he was also good to Elvis and had a good ear for music.

Back on top of Sand Mountain, Ira and Charlie Loudermilk became noted gospel singers around north Alabama. In the early ‘50s, they returned to Knoxville for radio appearances on WROL located on the top floor of the Hamilton National Bank Building at Gay and Clinch. WROL became the center of a new movement in country music known as “bluegrass” and served as the launching pad for such legendary artists as Roy Acuff, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Flatt & Scruggs, the Brewster Brothers, and the original Cas Walker Farm and Home Hour. It was while connected to WROL and living in Knoxville that Ira and Charlie changed their professional name to the Louvin Brothers because they thought they needed one that was easier to pronounce and spell. The Louvin Brothers became members of the Grand Ole Opry in 1955 and were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001. And to think they got their start while riding in a pickup truck on the way to the Knoxville Market House.

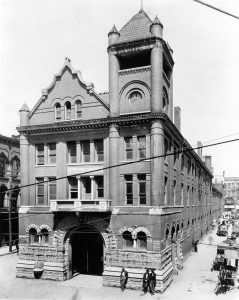

The Market House first appeared as a small building on Union Avenue in 1854, eventually expanding north to Wall Avenue. It was a tall, brick Victorian building with space for 60 vendors on the ground floor and space upstairs for public facilities, offices, and an auditorium, which became the first home of the WNOX Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round radio broadcast for a short time in 1936. With diagonal parking spaces on both sides of the building for truck vendors, there was only a narrow lane for moving traffic around the building causing considerable congestion. In 1960, a fire damaged a substantial portion of the Market House leading to its demolition, and the square where it once stood was transformed into the pedestrian mall we know today.

Good memories about good times, good food, and bad smells.