During the 1940s in the American South, Jim Crow laws segregated Americans. “Separate but equal” was the catch phrase. Black people were prohibited from using facilities designated for whites, such as water fountains, the “white section” of buses, “white schools,” and more. The laws in Tennessee strictly prohibited miscegenation and marriages between blacks and whites.

Bill Robertson was born in 1942, the son of a white mother and an African American father whom he likely never knew. A handsome youngster, he had green eyes and a relatively light complexion. People who remember say his mother, Sally Robertson, tried to enroll him at a “white school” in 1949 when he was six but was turned down because he was black.

She then tried to enroll him at Pleasant View, a “black school” a mile or so away. Mary McMahan, a black principal at Pleasant View (who had achieved the highest level of education of any teacher in Sevier County’s system) refused to admit him. Many believe that she did so in order to highlight the absurd consequences of segregation. Bill was neither black nor white, so according to the premise of the law, he didn’t belong at either school.

Bill was eight or nine when Sevierville Elementary School—a “white school”—admitted him. He was a little bigger than most of the boys and girls in his class, but otherwise fit in. He was a fun-loving guy, popular in school, and had a body-type suited for football. There being no football team at his grade school, his first experience (other than pick-up games on the school playground) was in his freshman year at Sevier County High School (SCHS) in the fall of 1959. He was quick and strong and immediately showed promise as a running back. Head coach Terry Sweeney practically adopted him, fed him well, and introduced him to the weight room. Principal Jack Ogle offered absolute support, and History teacher Julia Householder and her husband James provided Bill with a second home.

When Bill, number 40 for the Smoky Bears, began excelling in the sport, some were concerned. In the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the United States Supreme Court ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and ordered their desegregation—but set no timetable for the process to begin. By Bill’s sophomore year in the fall of 1960, the schools in East Tennessee had not yet integrated. Sweeney feared that other teams would refuse to play the Bears if they learned that Bill was of mixed race.

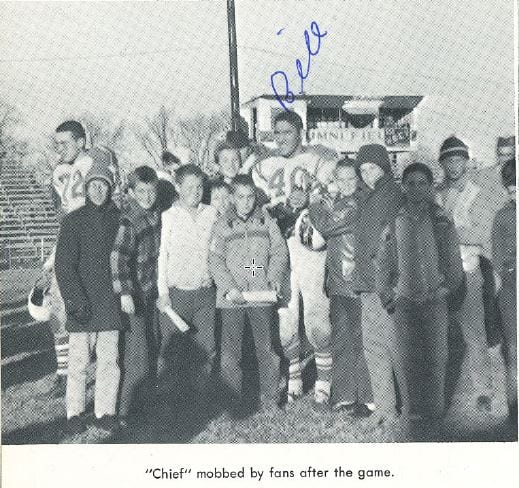

Native Americans did not suffer the same persecution as blacks, perhaps because the Eastern Band of the Cherokee tribe was only an hour or so away by automobile, and their teams often played the white schools in the area. So, in the early fall of 1962, Sweeney had a purple feather—reminiscent of a Native American plume—painted prominently along the center line of Bill’s white helmet, and he called him “Chief.” The name stuck, and no one refused to play the Smoky Bears.

Bill’s lifelong friend, David Williams, played quarterback for the Bears. In classic understatement, he later recalled that the team did a lot better when he handed the ball to Bill. In fact, the Bears became league champions—largely thanks to Chief’s tremendous ability. At the end of his last season at SCHS, he received practically every honor possible: All-Knoxville Interscholastic League, All East Tennessee, All-State, Player of the Year, and, notably, All-Southern—a first for the school.

Bill was a local celebrity, the most widely known player in the region, and easily the most popular student in school.

A local celebrity, the most widely known player in the region, and easily the most popular student in school (high praise because Dolly Parton was just a year behind), Bill was pursued by every major college in the South and even by the top program in the nation in those years—the Oklahoma Sooners, coached by the legendary Bud Wilkinson. Bill was not swayed by these recruiting efforts, which also included a personal visit from Bowden Wyatt of the University of Tennessee, a rare honor.

Bill enrolled at the University of Georgia. However, when Sweeney was hired as an assistant coach by his alma mater, Middle Tennessee State University, Bill followed his coach and enjoyed an excellent football career as a Blue Raider, and he earned a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree.

Together, Bill Robertson and those who had helped him grow were to have a lasting impact on East Tennessee. Early in 1963, just before Bill’s graduation from SCHS, Mary McMahan approached SCHS principal Jack Ogle to ask that he allow her grade-school students to be admitted there for high school. The only other option for these students was Austin High School in Knoxville, which meant they had to spend three to four hours on a bus each day. She explained that many chose to forego high school rather than endure that bus ride on a daily basis.

Mr. Ogle—a man of tremendous moral character—readily supported her request and solicited the school board for its approval, which it gave. In August of 1963, shortly after Bill graduated from SCHS, the school officially admitted black students for the first time. Two black students, Charlie Moulden and James Parton, joined the Smoky Bears football team.

Ogle was also a coach for the football team, and that August, the team sweated through a two-hour bus ride to Kingston, Tennessee for a pre-season scrimmage. When they arrived, Kingston’s school administrators met the bus and informed Ogle and Sweeney’s successor, Tom Bass, that they would not play SCHS unless Charlie and James stayed on the bus. Ogle directed the bus back to Sevierville.

Nonetheless, two weeks later, in the season opener against Young High School, Charlie became the first African-American to play in the Knoxville Interscholastic League. One year later, Knox County schools integrated. “My only regret,” Ogle later lamented, “is that I did not go to Mary McMahan first.”

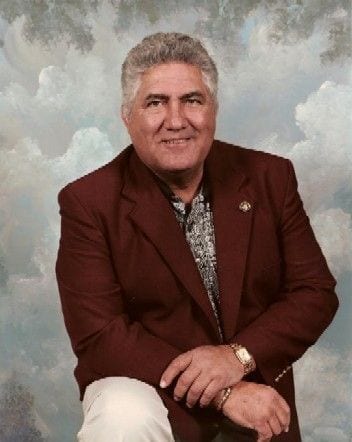

Bill “Chief” Robertson would go on to become a teacher, school administrator, and city councilman. Though he passed in 2011 after a long battle with cancer, his legacy lives on. Today, the Smoky Bears play on the Hardin-Robertson field, a tile wall in the Sevier County King Family Library shows Chief with football in hand, and Bradley County holds an annual golf tournament in his memory. Bill’s friends also established the Bill “Chief” Robertson Scholarship endowment to aid college-bound students at SCHS and Bradley Central High School in Cleveland, Tennessee—the honor of which he would undoubtedly have been most proud.

Loved this article as it brought back many memories of my childhood. The fan to the right beside Chief in the picture was myself. Would love to get a copy of the article with the picture.

Steve, we are so glad that you enjoyed your trip down memory lane. We can provide a complimentary copy of this issue if you swing by our office at 6812 Baum Dr between 8am–5pm Monday–Friday.

We loved Chief at our house. He was such a sweet, loving, caring man and our son played for him at Bradley High School. He was a great coach that brought out the best in his players but more than that, he loved every player and invested in their life…those things are eternal❤️

Proud to have had the privilege of personally knowing Bill through my life. Cant imagine how many lives he’s touched. Left this world better than he found it!